May 2000

As impassioned and animated offstage as behind his massive drumkit, Charles Hayward radiates a genuine intensity. He first came to wide attention as drummer with the highly influential This Heat as the embers of Post-Punk simmered off into wilder experimental tangents. He has released a dozen solo and colaborative albums, and puts on rare solo live shows which pull the raw muscular percussion at the heart of Rock into new shapes with devastatingly powerful results. The Freq team quizzed him on what makes drives his particular brand of rhythmic intensity as the London Musicians Collective’s Ninth Annual Festival of Experimental Music drew to a close on the South Bank in May 2000. Interviewers: Lilly Novak, Antron S. Meister, Iotar and Deuteronemu 90210.

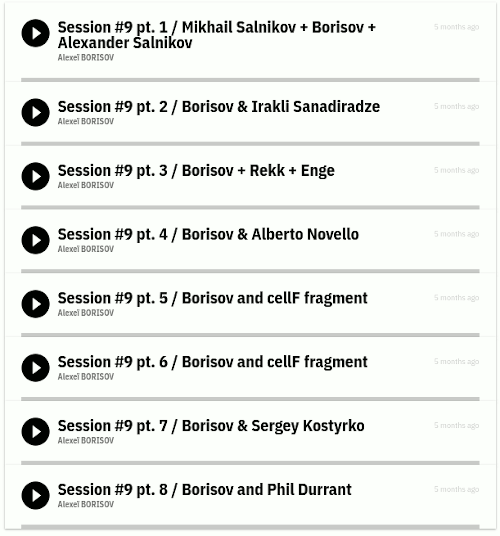

FREQ: We know about This Heat and all of that, but what you did yesterday in the LMC Festival, is that available on record?

Charles Hayward: None of that stuff last night is as yet recorded, though stuff within that line is. I’ve done some live recordings of that sort of material, this solo material, with tapes and drums and some voice. I haven’t done the material I did last night on record yet, and I intend to do that as a studio project. That’s really quite interesting, because I’m controlling chance in the way I’m trying to work, and in the studio you have the ability to go back and go over things.

FREQ: To clean it up?

CH: Not so much clean it up as make decisions after the event, and as I say, what I’m doing at the moment is controlling chance. So suddenly im going one step beyond that and starting to make something, so I’ve got a very difficult problem about how much to intervene and when not to.

FREQ: Doing a studio recording but compromising it in some way?

CH: No, I’m not compromising, I’m taking it somewhere else. Its another place, and I’ve got to be aware of the responsibilities of that place.

FREQ: Which are definitely different…

CH: Very different from the last album. I did three CDs based on a Japanese tour I did, and it was the vocals as they were live with me playing the drums. Now I can overdub the vocals. I’ve done lots of studio recordings before, but there’s a particular problem for me about this sort of music I’m doing at the moment and studio recording, and I’m looking forward to doing that.

FREQ: Watching you last night, there was so much energy, I kept thinking “My God, how can you do all this?” Your legs are going, and your hands and your arms and everything, and then you’re singing! That must be really, really difficult?

CH: No, no. I stretch every day, run or cycle every day, don’t drink, eat it rather than smoke it if you know what I mean…

FREQ: It was an amazing outpouring of energy; it’s contagious.

CH: That’s the idea of it.

FREQ: What is the essence of what you want to transmit to the audience? What would you want them to come away with?

CH: I want them to come away energised to forge their own reality rather that give into the one which is being shoved down their throats 24 hours a day.

FREQ: That came across particularly with the song about the information rich and the information poor… where does that come from?

CH: First of all it comes from a recognition that some of the arts admin people I work with, because I work with lots of youth music projects, and I work with disability arts projects, things like that, and sometimes their line is “Oh, we’ve got to get another computer before we can do this”, or they’re so overstressed by all this kind of stuff. For me, it’s like, a matchbox, an elastic band, and a bit of the times tables 3×3=9; fuck off and do it, don’t tell me what you need. So there they are, saying they need all this, and yet, when they get it, it’s still fucked up. The other thing I want to say about it all is that I’ve heard from lots of friends of mine who have access to the internet for instance, that they know that lots of the details and information put on there are in fact lies. People are talking about tours that they haven’t quite got together, they’re saying this will be happening blahdeblahdeblah. So it’s not information technology anyway, it’s mis-information technology.

FREQ: The Internet is all sorts of things – it is information and it’s mis-information and it’s disinformation…

CH: You’re right – but the other thing I don’t like about it is that it displaces us, and I actually celebrate more and more the live performance. I think I am here, now, I am not in four places at once, and in fact, I think that’s the luxurious life. So I’m going for poverty, becaue poverty is where I can find luxury. I’m going for my time, to make my reality, not giving my time to make their fucking reality which seems completely mad to me. It seems like slavery as opposed to luxury. So I think that poverty is in fact the luxury…

FREQ: Someone might say that that’s a cop-out for not wanting to catch up with technology?

CH: I was talking to my wife about Faust, and thay had a mixing system where one guy could change the mix and it would have a dynamic change of every other part of the sound. They could make it change for their own aesthetic, and that would affect everybody else who was playing’s thing.

FREQ: Which era Faust is this?

CH: Very early Faust, Uwe Nettelbeck-era Faust. But his was a dynamic system at work and being prototyped via music, 25-30 years before the technology happened. So who needs the fucking technology – we already do it. We already do it and they tell us they’re going to Borg us with fucking stuff into our brains and we won’t have to talk to each other. The thing is, telepathy was there beforehand, and when you get into intuitive arts like improvisation and stuff like that, you know that telepathy exists. So they’re telling us “You’ve got something and we’re taking it away from you and giving you rush hours, giving you television, we’re giving you all this crap, we’re giving you obligations, we’re giving you debt – debt is a big one – we’ve got your brain, now you’ve got no telepathy, now buy this shit and let us screw it into your fucking head.” That’s what I’m at with all that stuff. It’s already there!

FREQ: On improvisation, what was the influence of Can upon what you were doing in This Heat?

CH: I loved the way that they were intelligent and rhythmic. Intelligent and physical. Jaki Liebezeit is a master drummer.

FREQ: What do you think about Can now, in their various formations?

CH: I liked Club Off Chaos, what I heard of that, that was Leibezeit. Czukay is a remarkable man – it was only on the last one, Good Morning Story, that he started using digital technology

FREQ: Did you hear La Luna? It’s a very sparse 47-minute piece, done in one night, one take, bringing up tapes, samples drums, and tat’s very interesting because he’s just bringing all of these elements together in the studio, but then there’s also U-She‘s voice coming in on top of the mix and they make soemthing out of it that is ritualistic to an explicit degree.

CH: For me every performance is a ritual. I try at the beginning of the day to get myself in the right timeslip, if that makes any sense, where coincidence starts to happen as I’m cooking breakfast and things like that. People phone as I think about them phoning, and I try to get myself to that place.

FREQ: You’re trying to harness coincidence?

CH: I’m trying to tune into and harness coincidence. But that means in a way, not harnessing it, but tuning into it. Not harnessing it, because when you harness it you get megalomaniacal and stupid and you lose it. I’m not talking about controlling it, I’m talking about riding it as a way of being aware of it, going with it. With my two tape machines there’s no synching up point, so each time I start a song, it’s different. But it’s the same stuff, so I spend a lot of time in my rehearsal space just building up each sound like a painting. Then I go home and I eat with my kids, go back and listen to the sound again, and maybe do a tape of it, then go away for three days, come back and leave everything set up, then listen to it again and work it a bit more. So it reminds me more of a Rothko painting or something like that, I’m sort of like being with colours. The I let the machines go, and I get into a Zen funk state where I’m not thinking like deh deh deh deh deh (chops hands in a linear manner, snaps fingers arhythmically) and I’m looking out the window and I get into this place where I’m not thinking rhythmically, so that what come out is true to any sort of rhythmic reality because it will slowly sink in one way or another.

FREQ: Is there something related to the abstract impressionists about your method?

CH: I don’t know, but I do like the idea of a chaotic moment inside a frame. I’ve always found the rectangle a very funny contradiction in a way. There’s an edge to it, I like that you can have windows of chaos.

FREQ: When you came on to the stage yesterday, crawling slowly and then bringing the noise of the primal child out of yourself – when I saw that I thought “This man has been observing children”

CH: I’ve been observing children, but part of what I do now is more and more saying I did want to do this when I was twelve, but these people wouldn’t let me. they told me it wasn’t proper music. So I made a compromise and I did that thing with people where they played notes, but really I do want to do this, so in a way it’s being strong enough to do what I wanted to do when I was a twelve year old. And also it’s more sophisticated now but it’s the same basic ideas. I was doing stuff with my feet operating tapes when I was sixteen. I’d got that together by then.

FREQ: In terms of being a drummer, what’s your take on drum machines?

CH: Drum machines are very unsubtle. they don’t do what real drummers do. Real drummers, in a way they feel the throb in the room, and then they respond to the throb in the room and then they slowly manipulate it. So they go with what’s already been given and then they go up and down with it.

FREQ: What is that like for you?

CH: For me that’s true, even when they’ve given that this song is this fast, there’s ways of interpreting the space in between so that you can give it a bounce, or give it a straight ahead thing or whatever. It’s question that drummers can do that, start at one place and tweak it up quite quickly. Drum machines have got people by the short and curlies, because they’ve gone with where they’re already at. A drum machine doesn’t respond to what’s actually coming in at it; it has this idea of perfection, or correctness.

FREQ: It has an authority, even if its a false authority.

CH: It’s an authority which has got in the way of lots of musicians that I know. I mean, there’s also the other side to it, which is some musicians won’t face up to what the drum machine tells them. There’s a compromise between these two. Twyla Tharp did a whole dance piece with eleven humans and one computer dancer. When they were hanging out doing all that stuff, they watched the computer dancer doing these impossible things, one of them says “Hey, I see how he’s doing that!” and they’d go and do it too, and slowly human dancers were doing what before had been impossible, because they saw a computer model of the human form going that little bit further and climbing that little bit further up the wall. “I see why it’s doing that, it’s leaning a bit nearer to the wall, or it’s coming a bit further so it can use its leg muscles. Oh, if we excercise here, we can do that too” So these humans were able to do the impossible becayse they were seeing a computer do it. I think that it’s the same with Drum & Bass for instance; I like playing at that velocity now. Suddenly it’s very very possible, I’m actually doing it but I’m thinking at half the tempo. In fact you’re thinking at half that speed, playing at twice, and your brain is able to bob along nice and easy and this fast thing comes out. It’s only by listening to the drum machine, the Drum & Bass stuff I actually understood what I could do as a human. So I think we’re in a special time because the technology is giving us some insight.

FREQ: The method of the drum machine can inform after all?

CH: For me, I want to use that informatioin to evolve myself not give myself to the technology.

FREQ: Is it knowing what a drum machine can do, knowing what we weren’t doing before, but the drum machine is still programmed by someone – there’s an intentionality going into the machine?

CH: It’s not that so much, it’s like there’s an intentionality to the programming, but not an intentionality to each individual (raps out “knock knock knock” on the table) beat. After you set it up, there’s a flatness, whereas with a real drummer there’s an intentionality to to every single beat.

FREQ: So what’s the future for you?

CH: The future is make a new record, play a gig in Warsaw with Bill Laswell and Fred Frith, we’re in Massacre together the three of us, do Deptford X Festival of Arts, which is a visual arts festival . I’m doing a four-hour installation piece called Anti-clockwise which is for drums, tone generators and white light on July the First. Then I do a piece called Dikyodo, which is a Bhuto dance piece with LMC musicians that happened last year and is happening again this year on July 6th, and then I make the album. The I go on holiday to Minnis Bay, which is on the Kent coast near Margate, with my wife and three kids, and we have a little beach hut I just drink tea and make sandcastles.

FREQ: When’s the album being recorded?

CH: The album is recorded in late July, early August and is out in October, something like that, on Locus Solus, which is a Japanese label.

FREQ: Is the Japanese connection from their penchant for massed drumming groups like the Kodo Drummers?

CH: Nonononono, the connection comes in because of This Heat, Japanese people really loved This Heat, and that appreciation continued. The way the Japanese do things, they often need you to have someone to represent you, to speak to someone over on the other side who represents that person. It’s very surreal. So that didn’t come into place until 1995, so the first tour happened in ’96, which it would have been great to do with This Heat but it just never happened, so that’s how it’s developed from there. I played last monday with Fushitsusha, Keiji Haino‘s band, at The Garage. I’ve got good relationships with a few Japanese musicians. It’s great.

FREQ: How was that show?

CH: Very very loud, and a very strange lesson. I learnt a lot in the two days of rehearsing. I learnt about a sort of aesthetic that’s not my aesthetic, a different one. It’s a way of seeing intentionality and stuff like that syill, but for me, I like the social reality of rhythm, where everybody in a room starts to bob together when you build this thing even if it’s a quite tragic experience, where you’re singing the Blues or something

FREQ: Or you’re at a rave?

CH: Yeah, but I’m saying that even though the actual lyrics might be about how we’re all alone, but we’re not, we’re still in this ambiguous situation of being socially together. I love that, whereas Haino’s taken it to a place where we’re all completely isolated in our own nervous system, because the rhythm’s been so fractured, broken and taken down to each moment being left with no social containment at the same time. You really, really are in this place, which I found very extreme.

FREQ: Did you find that was the experience as a result of playing with Haino?

CH: I found it was very loud as well – the loudness was quite alienating actually – after a while I felt like I was in an isolation chamber.

FREQ: Do you think that’s part of his method?

CH: He’s got lots of methods, and I’m not knocking him. I really love what he does. It’s very extreme, very sexy, lots of stuff all at once. I love it, but it’s like “yeah, you go there because you want to go there”.

FREQ: If there’s a method set up, always you’d think, is there a way to break that method, and push it somewhere else?

CH: Yes! I feel that I was breaking it with the fact that I didn’t understand it fully, with an aesthetic that was quite strong, which was different, and also I think I was vaguely bringing it into relief by not being a Japanese person. I don’t know if I did, and I hope I didn’t break the aesthetic – a lot of this music allows for flaws and allows for schism. So it’s still not broken, even though there’s been a destruction.

FREQ: It’s moving it away from what was intended?

CH: Yeah, I like to try and respect what people do, and I did try and get as deeply into it as I could, and it was an unusual experience

FREQ: And you did learn from it?

CH: I learned a lot from it – I mean, it’s all about learning for me.

FREQ: How did recording with Coil on Love’s Secret Domain come about?

CH: I don’t know really, they got my phone number from somewhere or other and I went along and did about four hours.

FREQ: So, and this isn’t to put it down at all, was it like being a session musician in a way?

CH: I’ve got a part of me that sees different degrees: like there’s some stuff that i’m totally responsible for, there’s some stuff that I’m working in a very co-operative thing, there’s some stuff that i’ve got this very old traditional Jazz drummer technique skill and some guy wants to make this weird music that I don’t particularly understand but they want my skill and I’ve got this skill and I’ll go along and help ’em. Or, I’ve got other people who are R&B singer-songwriter mates where it’s just like they say, “do you want to come and play?” and I’ll just go and play it or I’ll say to them, “do you want to come and play?” and then I might even get into something else.

FREQ: Did you not understand what Coil was doing?

CH: Understand – no, I wasn’t saying that, I was saying that’s how I came about doing it in response to that thing about being a session musician! I’m only a session musician for the stuff I say yes to.

FREQ: And what if you went to America, and you went to New Orleans to one of the little bars on Royal Street where people have been playing together for thirty years and joined in with the musicians there?

CH: Last year I spent two days in a small town near Portland, Oregon, like something out of Twin Peaks. It’s out in the hills, and this old friend of mine, it’s a British friend of mine and he was a sound engineer for a lot of fantastic groups including This Heat, he’s changed his life because he became a heavy alcoholic so now he’s a member of Alcholics Anonymous. He took me on a Saturday night to his social, and he was very nervous about bringing me along to this place, is it too hick or whatever, and I ended up playing. Songs off Abbey Road and a couple by of Link Wray, that sort of stuff, and I had a groovy, groovy time. I run these things called Beehive with my wife on Saturday afternoons of innovative music, but children under 16 can get in for nothing. My ninety-year old mother in law and my fifty-six year old sister-in-law make cakes which are the hit of the afternoon They’re very very good wholesome food, sold at very nice prices. So, I mean for me it’s important to be able to do that – I see my mother in law, and I have a cup of tea with her and eat her cake. People come along with their families and watch – weird shit. Then, I don’t know if you know about Blue Peter, it’s a children’s TV programme, we have these little bits where an adult will say “This is how we make this instrument; would you like to come and help me?”

FREQ: “Here’s one i made earlier!”

CH: That sort of stuff – “I’ll have to do this bit because it’s got a saw”, for health & safety, all that sort of stuff. We do these at the Lewisham Art House, near where I live.

FREQ: I wish we’d had that when I was a kid!

CH: When I was a kid, my dad took me to the Festival Hall to see Ella Fitzgerald, Errol Gardner and Oscar Peterson on the same bill, and you can’t say fairer than that! This was like too fucking much, ah, it was just incredible the things my dad took me to see. I saw The Beatles when I was eleven, ten or something. I want to be able to do some version of that for youngsters. The weird thing is, if you give, it’s always re-learned. Each time the weird happens, it has to be rediscovered by each generation. So if you say to people this is the new ground zero – and by the way it used to be called the weird – this is the new level playing field, they’re going to take it when they’re sixteen or seventeen, and their going to take it way out.

FREQ: Could you give us a basic defintion of the weird?

CH: No!

FREQ: Thank you (laughs all around)! So when will the next Beehive be?

CH: Sometime in September – we get money from the local council, which is even the supreme irony of it, we get local money. It’s going to happen sometime in September-October that’ll be the next lot.

FREQ: Who out of anyone of all time you wish you could go and play drums with?

CH: I don’t really know. Well, I’m enjoying playing with my daughter at the moment. That’s really good. I have these dreams about when I’m a bit older and can’t play the kit any more – because it’s a very physical instrument, the kit – so maybe when I’m 65 I’ll do something else, and I have the picture that she’s the centre of it all and I’ll be really knocked out. So that’s a future dream. But, I do like Kate Bush, I’ve got a respect for her.. I don’t really know, it changes all the time. There’s a guy called John O’Lummy (check), he’s an Irish guy who plays bazouki, he’s a master musician, I mean a super master musician, fucking incredible.

FREQ: Would you only play with master musicians or would you be interested in playing with people who were fairly average?

CH: Well, I play with my daughter, she’s a starter. I do a lot of work with people with learning disabilities, in fact I’ve made records with people with learning disabilities, and not any old person with learning disabilities, people who can actually connect with music because of fate or destiny or something. I’ve gone into people’s houses to work with them, and some of them you’re just this sop to the fact that 99% of the time they’re just stuck in front of Jerry Springer and all that, and the TV’s on that little bit too loud, and then you go into someone else’s house, and it’s like this inner space thing, which I know about, a dispersed intelligence, so it’s not an intelligence here, some bits of intelligence are through out the entire body

FREQ: Maybe they can’t even control their bodies, but they can bring sound forth from it…

CH: They can bring whatever from it, movement. The thing is for me to take people seriously and say “you make that sound” and then I try and go with it. Resonance magazine has an article about the work I’m doing with people with learning disablities, which I feel very strongly about. Now I feel I’m saying it wrong, so it will come out sounding condescending, and I don’t mean it like that.

FREQ: What I was trying to say earlier, was to what extent do you feel that virtuosity has any virtue to it at all?

CH: Well, there’s people who’ve been playing for twenty years, and they’re still determinedly, completely incompetent and I think, what the fuck’s that? Some people, you go and listen to them, and it’s like they haven’t really done anything in ten years, they haven’t even fucking fixed that lead, if you know what I mean. So there’s that, and then there’s other people who’re just like connected. It’s very very raw, very very new, and that’s really really great. It’s just like, that’s the thing, as long as the room shakes, it doesn’t have to be virtuosity.

FREQ: Do they get worse as they head towards greater ability?

CH: They do, but sometimes, the thing is as a musician you’re trying to get something together that you can hear but your body can’t quite do it yet, and then you get a bit obsessed with doing that. Or there’s something you learn, like when I first of all realised that I could use roll techniques, I did that all the time, every song, all the time. I’m talking about very early playing, you get something and you get obsessed with it, so you’ve got to control it really.

FREQ: How about the other people who played this Festival? Did you listen to any of them and hadn’t heard them before and wanted to work with them?

CH: I like Hoahio, the two Japanese ladies, but I wouldn’t really want to play with them. I think if I did, I’d destroy what they’re really good at, but I really admired what they did. I didn’t actually catch Viv Corringham, because she was on before me and I never watch anyone before I play, if they’re going to give me things I don’t want to know. I’ve worked alongside Viv, I’ve gone to see her play with Pete Cusack, the guy who played the bazouki with her. I think she’s got a great voice, and Viv and Peter Cusack, they do these intricate things together.

FREQ: To go back to the earlier question about who you would like to play with, who of people you have played with is the one which has made the most impression on you?

CH: I suppose in a way, This Heat was the big learning experience. It’s the first time I felt, if you don’t like it, you can stuff it really. Put that in your pipe and smoke it; I don’t give a toss, I know this is what I mean, so I suppose that was like a manhood thing.

FREQ: When you get up there, and you’re in front of us, as an audience, and you make those sort of “fuck off!” kind of faces, what does that mean? It’s so aggressive, and so mean, and you seem like such a sweet non-aggressive person.

CH: I’m making eye contact. I want it to be confrontational, sometimes that gets out of hand, but I do want it to be like that.

FREQ: You do want a confrontation?

CH: No, it’s like the ball’s in your court in a kind of way. because I sort of know that I’m it’s like fuck off, there’s two tape machines, these three pedals, this fucking drum kit, and i’ll bash anybody’s face it if they come anywhere near me! (laughs all round) I will, I’ll fucking fight to death for this kit. And I’ve made this music, and what are you fucking doing?

FREQ: Exactly – you’re on the stage.

CH: I’m on the stage! I’ve spent three days getting to this place, and so I’m giving you this thing so what are you gonna give me, you know?

FREQ: And do we give you anything back?

CH: Yes, you give me everything back, in fact. You do, and sometimes I’m in tears. Yesterday was like getting through the day, but sometimes I’m in tears at the end of the gig, it’s true. Or I go off stage and I’m in tears, and I try and control it and I can’t. So yeah, I do. For me, playing live… I don’t know how some of the musicians I really, really love, they play live all the time. How can they do that? It must stop it from being heightened – it must become everyday. I’d rather turn down things – I’ve got a gig in three weeks time, I’ve now got to build up this energy in myself. For four nights before the gig I know I’ll get a wave of fear, and I won’t be able to sleep.

FREQ: Is this about indigestion? (laughs all round)

CH: A good regular bowel is the secret! (big laughs)