OK, so I’m interviewing Justin Sullivan of New Model Army and I’m shitting myself; one of the finest living British songwriters, veteran of a 30-plus-years of playing kick-ass protest rock’n’roll, a man who’s played more good gigs than I’ve had bad ideas… no, this won’t be awkward at all. But I’d be a dumbass to pass up the opportunity – and I’ve seen interviews where he’s been very patient with people even more inept than me – so here goes! I dial.

OK, so I’m interviewing Justin Sullivan of New Model Army and I’m shitting myself; one of the finest living British songwriters, veteran of a 30-plus-years of playing kick-ass protest rock’n’roll, a man who’s played more good gigs than I’ve had bad ideas… no, this won’t be awkward at all. But I’d be a dumbass to pass up the opportunity – and I’ve seen interviews where he’s been very patient with people even more inept than me – so here goes! I dial.

And here he is! Talking! In person! And he’s a very agreeable chap. He very kindly takes a break from compiling vocals on the forthcoming new album (of which more later) to talk to me about, among other things, “something that happened 73 years ago or whenever it was…” – the seminal debut Vengeance, recently re-released in a format that can only be described as EPIC. While I try to keep my heartbeat somewhere beneath the legal limit, he tells me how this came about.

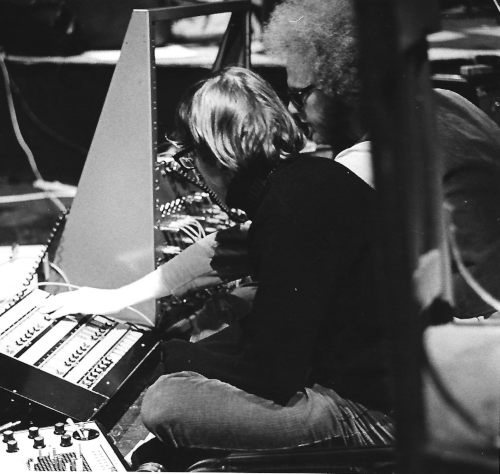

“It was a sort of long process, actually, because we’d started talking to Abstract about buying the rights to it about three years ago. And around that time we were thinking about it, and they offered us a price, we negotiated, and then we settled for what we thought was quite a bargain. And Abstract to their credit were really helpful at all stages, actually, making the record, putting the record out and then letting us take it on, so thanks to them really. I guess at the time we listened to it and thought ‘yes,’ and then it was a bit of a long process by which we thought ‘you know, there’s some other material out there we need to get hold of’ and we got hold of some of the original masters of it, done on 4-track cassettes. And it’s almost a whole album’s worth, nine songs previously unreleased. And then we were kind of getting ready, a year and a bit ago, and it was all sat in our studio, and then last Christmas Eve in 2011 our studio burnt down. So we lost a lot of the original, the better-quality recordings of some of that early stuff, and then everything was a bit on the back burner. We had to re-equip ourselves, we were finding a new bass player at the time, etc, etc, and we were trying to write an album so we put everything back and then just in Autumn we finally went ‘look, we HAVE to do this Vengeance thing’, we’d been sitting on it for ages, and by this point we were already making the new album. I didn’t have that much to do with the process, I’ll be honest.

“It was a sort of long process, actually, because we’d started talking to Abstract about buying the rights to it about three years ago. And around that time we were thinking about it, and they offered us a price, we negotiated, and then we settled for what we thought was quite a bargain. And Abstract to their credit were really helpful at all stages, actually, making the record, putting the record out and then letting us take it on, so thanks to them really. I guess at the time we listened to it and thought ‘yes,’ and then it was a bit of a long process by which we thought ‘you know, there’s some other material out there we need to get hold of’ and we got hold of some of the original masters of it, done on 4-track cassettes. And it’s almost a whole album’s worth, nine songs previously unreleased. And then we were kind of getting ready, a year and a bit ago, and it was all sat in our studio, and then last Christmas Eve in 2011 our studio burnt down. So we lost a lot of the original, the better-quality recordings of some of that early stuff, and then everything was a bit on the back burner. We had to re-equip ourselves, we were finding a new bass player at the time, etc, etc, and we were trying to write an album so we put everything back and then just in Autumn we finally went ‘look, we HAVE to do this Vengeance thing’, we’d been sitting on it for ages, and by this point we were already making the new album. I didn’t have that much to do with the process, I’ll be honest.

Given that the songs were recorded over three decades ago, I wondered how it felt to revisit them. Although NMA have never shied away from interspersing older songs into their live shows, I was interested to know how he’d reacted to the tracks themselves, in that form. “One of the things that struck me,” he says, “was how good the musicians were. Obviously Stuart Morrow was an extraordinary talent, and basically everything started for me when I bumped into him in 1976 in some youth club in Bradford, 1977 actually, and we started various bands before we started New Model Army in 1980. And obviously he was quite a phenomenon. But actually, both the drummers, both Robert’s predecessors, Phil Tomkins and Rob Waddington, were really good drummers. I was very lucky in the people I met early on.”

In particular, I was interested to know his feelings on “Spirit Of The Falklands,” the one track on the album whose subject matter pinned it down to a specific time and place, and therefore the one track that should, by rights, be the most dated. For me, I tell him, it still seems entirely relevant; the battlefields may change, but the same stories replay themselves and the body bags still mount up. He agrees. “Having not played that for 25 years we played it at Christmas this year, we played it at all the Christmas shows this year, and it was good to play, and it was quite strange; both musically and lyrically it felt very now. I always thought “A Liberal Education” was a very interesting lyric for its time, and an interesting song musically. I remember when we made Vengeance we had five days to make it in and we spent a whole day on that song, which was unheard of in those days – you could spend a day on a song? Trying to get it right. And I look back and go, yeah, both lyrically and musically we were very creatively ambitious from the very beginning. We didn’t want to do what everybody else was doing. Yes, we were influenced by punk, and yes we were influenced by all that stuff going on around us, but from day one we were trying to do something, I dunno, just different. Interestingly enough there’s a song on the new album which is as yet untitled, actually, but it’s almost like that idea revisited thirty years on. It’s a critique of the whole baby-boomer ethos. No, critique is probably putting it a bit too pretentiously”, he laughs, “a howl, a scream of rage at the baby boomer ethos.”I ask him how he thinks the world has changed in the last thirty years.

“Who are we talking about? The human ape, have human beings developed? Thirty years is the blink of an eye. Civilisation? Again, blink of an eye, isn’t it? Are things better or worse than they were thirty years ago? It’s like all these things, some things are better, some things are worse. People at their core aren’t any different, though. If you’d asked anybody 35 years ago what do you see if you look into the future, well you see the pressure of population. That’s still there. And the pressure on resources; well that’s ever more increasing as other parts of the world desire what we have. You see the decline of the West, perhaps, as against the rise of other parts of the world, that was coming, I would say, looking back to the ’70s, that was definitely coming. There is one interesting thing which is that I think that round the time the band was starting, which is at the beginning of the ’80s, there was this philosophy which swept the world, which was the neo-Liberal philosophy, allow the markets free rein and everything will become balanced and they will just create wealth and everyone will be happy. And I remember thinking at the time – [as well as] various people, I certainly wasn’t alone: I’m sure this is not quite as simple as that. And sure enough, this philosophy swept the world, and it isn’t over yet, but I think since 2008 it’s in trouble. I have a friend from East Germany and he says the current situation reminds him of the last days of the DDR. I said what do you mean? He said, well everybody knows the system doesn’t really work, but no-one knows how to fix it.” Perhaps more than any of their contemporaries, New Model Army have always been famous for the devotion of their fanbase. I ask him if he has any idea why that should be, and what should inspire such fanaticism.

Perhaps more than any of their contemporaries, New Model Army have always been famous for the devotion of their fanbase. I ask him if he has any idea why that should be, and what should inspire such fanaticism.

“I think there are two or three reasons, one is perhaps that we have never had a top 20 single, ever, in any country in fact! So we haven’t got stuck anywhere, we’ve always kept moving. All that fanbase people talk about, ‘ooh, the New Model Army fans,’ as if they were all one voice – they’re not at all one voice, they’re all sorts of kind of different people from different walks of life, from different countries, they’re different ages and they discovered the band at different times, so they’ve all got their different favourite eras. Meanwhile the band’s kept moving, so we haven’t got stuck anywhere, know what I mean?

“I think the other thing is, the music and the words – the music’s kind of eclectic, it borrows from everywhere, we never wanted to get stuck in any musical genre. We’re a bit like that Groucho Marx thing, we refuse to be members of any party that would have us, so to speak, we refuse to join any club that would have us. So we’ve always been outsiders musically. And then, I think, the songs are about things, they’re not just about one thing, they’re about an awful lot of things, there’s politics, there’s comments on what’s happening in the world, there’s stuff about religion, there’s stuff about relationships, there’s a lot about family relationships which kind of affects people very differently, and there’s all sorts of different ideas about life. And I think what happens is people get drawn into that. And because there’s not one central philosophy, there’s just lots and lots and lots of different ideas, people find in New Model Army something for every moment. When they’re going through this experience, that song suddenly means an awful lot, and when they’re going through a different experience – there’s something for every experience almost. Again because we never allowed ourselves to get put in a box.“Vengeance is a case in point in the sense that the times were very political, and then there were rumours of this new red-hot, Red, Socialist band coming out of Bradford. And then the first thing we do of note is to release Vengeance, with a title track which is deeply politically incorrect. And then immediately all the left-wing people who were our natural allies all went ‘Oh my God, we can’t really support this band!’ I remember there was the whole Red Wedge thing in the 1980s and we were pointedly not invited to be part of these things because we couldn’t be relied on to say the right thing.

“As the guy that writes most of the lyrics I think that songwriting is of the moment, and it’s about emotions. Politics or philosophy are about having an argument and arguing it, but I don’t think that’s what music’s about at all. Music’s about emotional expression, and emotions are contradictory. So you might feel like vengeance one day, and you might feel full of forgiveness a different day. That’s a normal sort of way of being. And given the fact that music to me is about emotions and what you actually feel, that’s the way we went. And that had us excluded from all the left-wing political things of the ’80s.”So paradoxically the thing that excluded some was the exact thing that strengthened the bonds with the people who got it, I suggest.

“Maybe. Yeah, that’s right. People that got it, that we weren’t trying to put across a philosophy, we were talking about how things feel. And then that really bound them to us, I think.”

It’s a devotion that’s taken them around the world many times over, and seen them garner a reputation for being one of the hardest working bands on the planet.

“It’s very strange for us, because at all stages in all 33 years, 32 years or whatever it is, we’ve been a little band and we’ve been a bigger band, and sometimes we go around the world and stay in four-star hotels and get treated like demigods, and three weeks later we might be in a different country where it’s a budget tour and we’re sleeping in very cheap hotels and sitting in the back of a van for hours. We do a bit of everything. I think that’s quite good too. Yes, we’ve played to 100,000 people, yes, we’ve also played to 12! And actually, someone was saying to me a bit ago about the early ’90s, about how we were sort of poised to become quite a big band in the very beginning of the ’90s, and it never quite happened, and why is that? And one reason someone put forward is perhaps we just didn’t want it, in the sense that all of us, when we go to see our favourite bands, we want to see them in the old Marquee, or in some 400-capacity venue. That’s where you want to see your favourite band. You don’t want to see them in a sports hall or some huge arena somewhere. Although it’s kind of exciting going out in front of hundreds of thousands of people, on really big gigs or festivals or whatever, or even those sports hall gigs, which we still do from time to time, nothing beats a 300, 400-capacity venue packed to the rafters where the audience is kind of on top of the band, and everything’s just so intense.” I wonder if the fact that they deal with feelings, and feelings are universal, goes some way towards explaining why such a quintessentially British outfit have come to have such a huge following on the Continent.“The starting point is that it’s universal. Actually the problem for us in Britain is the opposite – although the themes are British, this kind of openly emotional way of dealing with things is very un-British. If you think about what has been championed by the British media over the years, it tends to be stuff which is knowing, it has a sort of knowingness about it, a slight sense of irony, as if it’s a bit uncool to get really, really worked up about these things. So that if you think back to the ’80s, the Smiths were perfect in that sense, because they’re very British. And although in one way their stuff’s very emotional, in another way it’s slightly removed. You don’t get the sort of open passion when people just scream, or just play everything too fast and too loud and too… you know what I mean? Where they actually really lose themselves in it. And that was the thing about New Model Army. We’re were not afraid to do that. And so to the British, certainly the middle-class artistic part of the British public I think we were always a bit too much. A bit too openly emotional. It’s a bit distasteful to the British. If you go abroad it’s different.

“We’ve always done very well in Germany, I think there’s something in the German thing that there’s this kind of contradiction – they’re terribly, terribly direct, but at the same time they’re terribly romantic. And I think there’s strains of that contradiction in what we do. It’s terribly romantic but at the same time terribly in your face.”It’s one thing to decide you’re going to deal with feelings, quite another to be able to articulate those feelings to others. I ask him about his writing process, and in particular who inspires him.

“Well, let’s start with the fact that I live with a writer, so I think you gotta start with Joolz”, (Denby – artist, poet, and author, whose wonderful Billie Morgan was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and is highly recommended to, well, anyone). “I don’t find writing particularly easy – I can do it, and I’ve written a couple of decent songs in my time, but it doesn’t come pouring out of me. I work quite a lot on it, so I’ve always admired writers who just sit down and it pours out of them, of which obviously Joolz is one. So I think that as a writer obviously she’s sort of first. When I was growing up I listened to a lot of Bob Dylan, I like a lot of Americana actually. I like Bruce Springsteen‘s country stuff; his rock and roll got a bit bombastic, but I think his Ghost of Tom Joad and Nebraska are wonderful albums; you know, story songs.

“I just think story songs and writing in pictures seem to me the most natural and interesting thing to do, that’s what I like. I love American country music in that sense. The music’s kind of repetitive, but the stories – everyday stories of everyday folk – I find them irresistible if they’re well-written. Stories are the most basic form of human culture, probably. I hate lyrics which are about the inside of the writer’s head endlessly, endlessly, endlessly. It’s not interesting. Out of 200 and something songs, I’ve written 20 or 30 that are quite personal. But the rest are other people’s stories. Things I’ve seen, things people have told me. Maybe that’s why they’re all so contradictory, because you take a point of view which isn’t necessarily your own, and write that person’s story. I love doing that.”I tell him that for me there’s always a sense, on cracking open a new New Model Army album, of settling down with a book of great short stories.

“Yeah, and they all include weather, apparently. Someone said to me ‘your songs are like a fucking weather forecast’. And the sea, I’m obsessed with the sea. I have to be careful about that now though, because Michael (Dean, NMA drummer) loves mountains rather than sea, so there has to be an equal amount of mountains. So you might see a lot of mountains in recent albums. But yeah, nature imagery, that’s what I like best. Big open spaces, or the water, or looking at the sky. I spend a lot of time looking at the sky. It never gets boring. So there’s a lot of that.“I also think that when you’re listening to a lyric, the first thing you want to know is where you are, what time of day it is, and what the light is doing. And then, as soon as you receive that information you’re somewhere else from where you are sitting listening to the music. And in the sense that music’s meant to transport you to somewhere else, either inside yourself or to some external place, but it’s of the imagination. I always think that about radio plays. I love radio plays because your imagination fills in everything. When you’re given film you’re given too much information. It’s all there in front of you and you sort of take it in. But what happens when you listen to radio plays or listen to music, particularly story songs, is that your imagination fills in, you contribute to making the pictures. So I think it’s actually more involving, and that’s one of the reasons it’s stronger. How many times can you watch your favourite film? Twenty? Thirty? How many times can you listen to your favourite song? Infinite. It’s kind of stronger somehow.”

On the live album And Nobody Else, he states in between songs that “Modern Times” is HIS favourite New Model Army song. I wonder if that’s still the case.“Well it was at the time,” he laughs. “It’s up there. I’m like anybody else – my favourite ones are the ones we’re working on right now. I’m sure all bands and artists and musicians you talk to would say the same thing, ‘my favourite song is the one we’re just doing at the moment.’ Especially as we’ve been quiet since Today Is A Good Day, partly because of the anniversary things, partly because of the fire. We’ve lost a couple of years, really, and now we’re back into making quite a different record, quite a special record, and we’re terribly in love with it…”

Ah yes, the new album. An enigmatic press release promises something a bit different. I wonder if he’d like to elaborate on that…

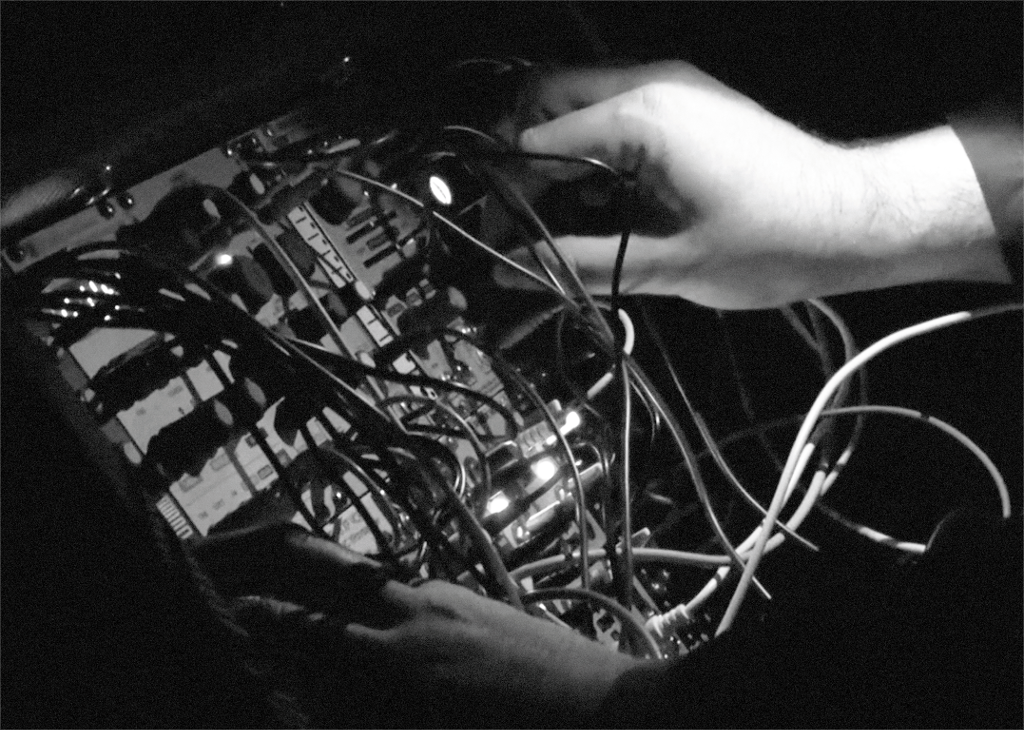

“Not really! Only what I’ve said already, which is that the last couple of albums were rock band in a room albums, and this is not. We haven’t worried about how to do this live, we’ve allowed ourselves to just make sounds we wanna make and sort of layer up stuff in a way that’s interesting to us without wondering about how we’re gonna do it live. And we’ve just about finished, and we’re just waiting on the guy that we hope is gonna mix it, and I dunno if I’m allowed to say this yet, but I’ll say it anyway. It may not turn out this way, but it’s probably Joe Barresi with any luck. Who’s known for doing Soundgarden, Tool, Queens of the Stone Age – rock. Although the album isn’t at all rock, although we want it to have that kind of… aggression, perhaps? We’re nearly done recording. It was always our intention to basically produce it ourselves, record it ourselves, because we wanted to be able to take time and go up all sorts of blind alleys and just try things. Which if you’ve got a producer sitting there and you’re paying them, it doesn’t really work. And then it was always our intention to explore all sorts of ideas and then give it to someone really good to mix. So that’s still what we’re planning to do. And as I say we hope it’s Joe Barresi, it’s just to do with scheduling and stuff like that now, I think.”And off he goes, back to work. I thank him for his time, wish him luck with the album, hang up, and collapse in a heap on the floor.

And this morning, editing this piece and pulling together all the varying strands of conversation into some kind of order, I go online to check a couple of things and find that New Model Army have now finished recording and are currently in LA mixing the album – with Joe Barresi. So on top of everything else, there’s a happy ending. And a no-doubt-amazing album well on the way. In the words of their last album’s title track, today is a good day.

-Deuteronemu 90210 quivering in a heap on the floor-

2 thoughts on “An interview with Justin Sullivan”

My interview with the amazing Justin Sullivan is online now- http://t.co/7P2ReLwp11

Eight years later and still a good read. Thank you!