Dingwall’s, London

27 April 2011

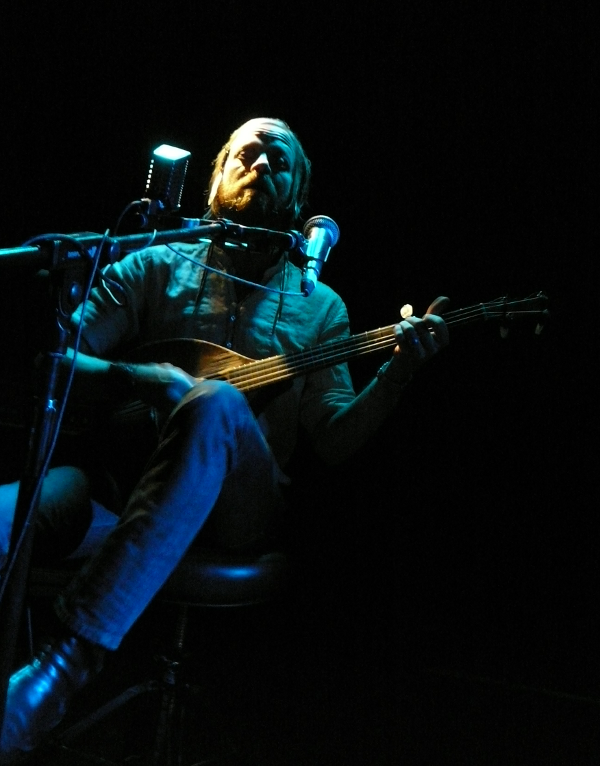

Though this gig is billed occasionally as a [post=”wovenhand-ten-stones” text=”Woven Hand”] performance, it’s decidedly David Eugene Edwards‘ show from the moment he steps onstage to a rapturous welcome. Accompanied by Woven Hand man Jeff Linsenmeir on various forms of percussion and keyboard, Edwards dispenses with onstage banter, instead launching into a set which covers his back catalogue including a goodly selection of 16 Horsepower songs.

Though this gig is billed occasionally as a [post=”wovenhand-ten-stones” text=”Woven Hand”] performance, it’s decidedly David Eugene Edwards‘ show from the moment he steps onstage to a rapturous welcome. Accompanied by Woven Hand man Jeff Linsenmeir on various forms of percussion and keyboard, Edwards dispenses with onstage banter, instead launching into a set which covers his back catalogue including a goodly selection of 16 Horsepower songs.

Using every available limb at their disposal to play a multitude of instruments and FX, he and Linsenmeir perform with all the volume and density of a full band in a truly impressive display of how to travel light and rock hard as a duo. Together, they make the songs their own – and while the focus my be on Edwards, Linsenmeir is the perfect sideman, contributing solidly and seriously to the sounds coming off the stage. What songs they are too; few could write them, still fewer deliver them with the almost monomaniacal, evangelical intensity of Mr Edwards. Just like the effect his presence and performance has on sections of the crowd – some of whom weep openly with the power of his songs – he seems to be possessed of rapture himself, backlit and with eyes mostly closed. As he plays, Edwards works up a sweat of concentration, occasionally expectorating onto the boards like the wild West folks of old who inspire him as much as the native Americans (whose beads and feathers he wears and whose chants he interjects between songs) or the God of his father and the big wide skies.

Edwards’ Christian inspiration is as unavoidable as the crucifixion was for his messiah, but this is a very personal Saviour indeed, one whose poetry is expressed in imagery of nature and of animals (herd, wild and working), of humans and their ways, both good and bad. Impassioned as Edwards’ and Linsenmeir’s music is, as much as his fingers work their magic on the strings of banjola and guitar, as the feet stamp out belled-rattle rhythms or trigger the keening background looper drones, it all comes down to the voice. He could simply sit and sing these song in his ageless, far-distant voice, without need for the reverbed twin microphones he switches narrative voices between – one crackling with steeped-back RCA age, the other clean and strong – and they would unfailingly move the hardest of atheistic hearts with their beautiful truth.

Edwards’ Christian inspiration is as unavoidable as the crucifixion was for his messiah, but this is a very personal Saviour indeed, one whose poetry is expressed in imagery of nature and of animals (herd, wild and working), of humans and their ways, both good and bad. Impassioned as Edwards’ and Linsenmeir’s music is, as much as his fingers work their magic on the strings of banjola and guitar, as the feet stamp out belled-rattle rhythms or trigger the keening background looper drones, it all comes down to the voice. He could simply sit and sing these song in his ageless, far-distant voice, without need for the reverbed twin microphones he switches narrative voices between – one crackling with steeped-back RCA age, the other clean and strong – and they would unfailingly move the hardest of atheistic hearts with their beautiful truth.

It is not necessary to share any of David Eugene Edwards’ beliefs, merely to recognise them, to feel the wind in the hair and the desert heat, even from within a Camden Town venue as the keening tale of woe and badlands necessity told by “Outlaw Song”strips away the urban grey and replaces it with bright-lit scrubland starkness. Truth be told, it’s probably not even necessary to comprehend English to get the passion, the strength of purpose everpresent in these words, in these songs. But for those who do, the listener is not merely put in the place of the protagonist and his sixgun taking on the law in want of his horse in a futile wilderness confrontation as evocative and as resonant as anything Cormac MacCarthy has written, but is just as swept up by the course of events described with as elegiac a touch and the same lingering sense of inevitablity, of time and place. Likewise, there is the sense of having walked the “Hutterite Mile” in Edwards’ company, of being shown a world, interior and exterior, so vastly different from the modern cityscape (or countryside, for that matter) as to be almost mythical, just like the West where a terrible god – and sometimes more terrifying people – holds sway.

It is not necessary to share any of David Eugene Edwards’ beliefs, merely to recognise them, to feel the wind in the hair and the desert heat, even from within a Camden Town venue as the keening tale of woe and badlands necessity told by “Outlaw Song”strips away the urban grey and replaces it with bright-lit scrubland starkness. Truth be told, it’s probably not even necessary to comprehend English to get the passion, the strength of purpose everpresent in these words, in these songs. But for those who do, the listener is not merely put in the place of the protagonist and his sixgun taking on the law in want of his horse in a futile wilderness confrontation as evocative and as resonant as anything Cormac MacCarthy has written, but is just as swept up by the course of events described with as elegiac a touch and the same lingering sense of inevitablity, of time and place. Likewise, there is the sense of having walked the “Hutterite Mile” in Edwards’ company, of being shown a world, interior and exterior, so vastly different from the modern cityscape (or countryside, for that matter) as to be almost mythical, just like the West where a terrible god – and sometimes more terrifying people – holds sway.

Edwards is able to rouse the endless desert found inside a person as much as the ones spread across the south west USA, not just transporting the audience to the site of his vision but calling up the black-clad bad guys carried around inside everyone, summoning a visitation of personal desolation and redemption on an individual level. His skill is not just to take the audience out of themselves and their environment, but to make it so real and present as if he were sat down telling tales around an campfire, striking up a song and drawing in the story round the flames. And like those flames, the words and music burn bright in the stage-lit night, speaking of a terrain and worldview so far distant, yet at once so much of the here and now too.

-Richard Fontenoy-