Llanberis Slate Museum

25 March 2011 to 3 Aril 2011

It was a soul-destroying experience to grow up in Wales back in the seventies in the knowledge that your entire country had only ever produced one single role model of any value. The frustration was further compounded by the fact that hardly anyone here seemed to have even heard of him, certainly not the Welsh media, and the few exceptions usually knew him as “that bloke who used to play with Lou Reed.” Throughout the eighties, I would regularly play people Music for a New Society, pointing out that the author of this work of obvious genius was in fact Welsh, only to be faced with blank stares.

It came as something of a shock in 2009 then, when John Cale was chosen to officially represent Wales at the 53rd Venice Biennale. It seemed that the powers that be had actually woken up, if forty years too late.

Cale’s installation Dyddiau Du/Dark Days is a wonderfully unlikely piece for any country to choose to represent itself on the international stage, saturated as it is with the repression, tedium and bleak hopelessness endemic in traditional Welsh society. Following its appearance in Venice, the installation had its first Welsh showing last year in Swansea and now comes up to the north for the first time.

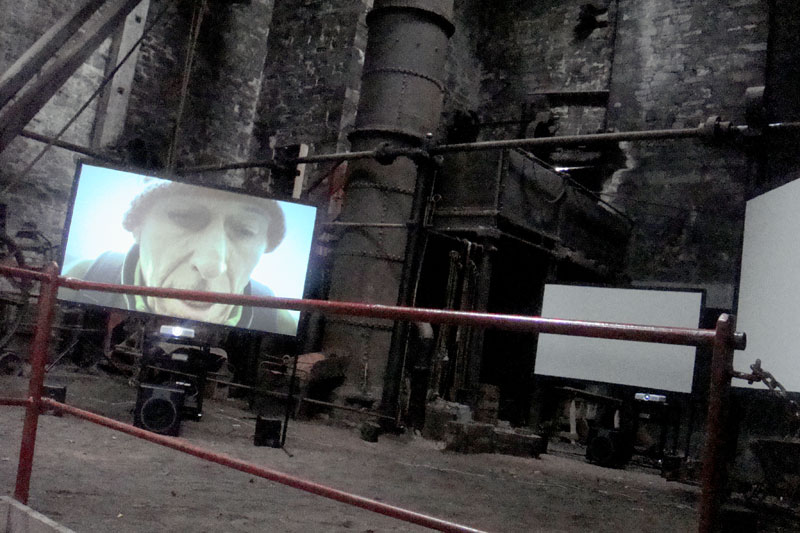

Arriving at the National Slate Museum in the small mountain quarry community of Llanberis on a grey wet Wednesday morning, I’m directed to the old quarry foundry – a huge cold, damp space filled with decaying industrial machinery, all rusty winches and crumbling furnaces with rows and rows of mysterious implements hanging from racks around the wall. Set among the relics are five screens and around twenty PA speakers. In the midst of all this are set out four chairs for the public, of which I seem to be the only one.The piece lasts for an hour and then loops. It consists of four sections, entitled Maes-Y-Wern, Send Me Away, Dreaming in Vertigo and The Making of Unpretty. I’m not sure of the importance of the order of the pieces as I’m told it is different here than in Venice, but anyway I arrive at the start of Dreaming in Vertigo.

Dyddiau Du/Dark Days moves at a glacial pace, echoing Cale’s earliest work in the Dream Syndicate with LaMonte Young. For much of the time the speakers transmit the slightest murmurings of ambient location sound, occasionally bursting into the foreground with fragments of music or narration, while the screens remain largely blank, with seldom more than two used at any one time, although the need to constantly look behind in case you’re missing something adds an extra discomfort to the experience. The ambience of the quarry itself bleeds through the open doorway, creaking machinery, the wind and rain and the sound of workmen wheeling materials around on trolleys all fuse with the recorded sounds to bridge time and space.Dreaming in Vertigo features close footage of Cale’s face as he scrambles up the twelve hundred slate steps in Dinorwic Quarry, oddly visible in real life through the foundry’s open doorway (not the case in Venice or Swansea, obviously). As he struggles up the harsh incline in the winter snows, he breathlessly gasps over and over “I didn’t do anything, Mum”, which his notes tell us was his response to being accused as a child by his own grandmother of being the cause of his mother’s breast cancer on account of his English blood. Cale’s physical and emotional pain becomes increasingly uncomfortable until his familiar calm voice bursts from another set of speakers, disembodied as if down a telephone, with impressionistic poetic reflections of his unhappy childhood. Here he glimpses a way out: “take your mind and put it far far away – perhaps in another country.”

Cale’s primary inspiration for Dyddiau Du/Dark Days was his attempt to come to terms with having lost the Welsh language. Until he was seven, he spoke Welsh exclusively, living with his maternal grandmother who forbade the use of English in her house. This prevented him from ever communicating with his father, an Englishman. He comments in the notes “I had three strikes against me from the beginning – I was the son of an Englishman, the Englishman was uneducated, and worse still, he was a coal miner.”The situation instilled a determination to escape at any cost, concentrating his effort into earning scholarships to first London and then New York. He succeeded in escaping, but at the cost of losing his mother’s language, a loss that haunts him to this day.

The Maes-Y-Wern and Send Me Away sequences use footage and recordings made in the old family home in Garnant in South West Wales. Cale by chance found the old house to be vacant and arranged access with the current owners. Here we see bleak empty rooms with peeling paint, hear the traffic pass outside and catch distant ghostly glimpses of Cale playing the piano in the next room. However solid the house looks and however ghostly Cale appears, there’s no mistaking that it’s the house that haunts Cale and not vice versa. At one point, Cale walks into a room and sits at a piano without playing a note before getting up and leaving. It seems both a reflection on the debilitating effect of the parochial community and a homage to John Cage who would eventually show him the freedom in New York that he was denied here in Garnant.

The most disturbing section is The Making of Unpretty, where the snail’s pace is brutally fractured by jarring violent images of Cale, bound and blindfolded, being waterboarded to the strains of Welsh choirs and rugby crowds. Painful to watch, it’s a visceral and righteous indictment of the disabling attrition endured by the active mind in traditional Welsh culture. The footage shudders and breaks up, replaced by a loud churning drone, without images, that for the first and only time uses the full volume of the sound system, resonating around the foundry’s musty walls for a full quarter of an hour. The eternal drone that Cale found his escape through in New York back in the sixties? Or perhaps an obliterating barrage to block out the pain? Maybe they are one and the same.Overwhelmed by the experience, I stayed and watched it go round a second time… probably the most disorientating Wednesday morning I’ve ever spent. Dyddiau Du/Dark Days is a most worthy addition to John Cale’s impressive artistic CV; in applying so deeply personal and honest an approach, he has actually succeeded in encapsulating the essence of Wales more accurately than anyone before him.

-Alan Holmes-

One thought on “John Cale – Dyddiau Du/Dark Days (installation)”

Excellent piece.

I wish I’d seen this.