Like the conflict minerals that fuelled much of the Second Congo War, good news stories emanating to the West from the DRC have therefore been in precious short supply. The emergence of Konono No.1 (if one can talk of a group that had actually been extant since at least the 1970s as being ‘emergent’) has, over the past five or so years, helped in some small way to rebalance perceptions of the DRC and popularise what has come to be known as ‘Congotronics’, Konono’s patented brain-shredding combination of traditional African forms with overdriven junkyard electronics.

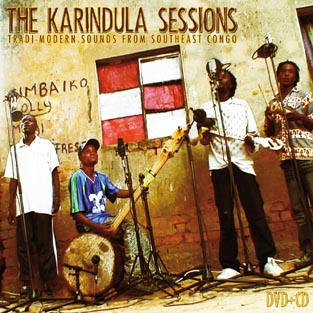

With the West hungry for more, Konono’s producer Belgian musician Vincent Kenis has now travelled to Lubumbashi and documented a three-day mini festival of Karindula, issued here as a six track CD and accompanying 90-minute DVD. What a handsome package it is too, from the lovingly put-together fold-out sleeve (complete with ‘in action’ photos of both musicians and audience) to the translations of the call and response song lyrics, and this release works for both the initiate, as a deeper delving into the vast pool that is African music, and for the neophyte, as a wonderful introduction to the subtleties and complexities of the continent’s ever-evolving musical forms. How could you resist a track with a lyric such as “What do you call the spinal column of a salted fish?” The CD component features a half dozen tracks, three from the ‘band’ BBK, and one each from Bena Ngoma, Bena Lupemba and Bena Simba. These are long sinuous work-outs, sometimes up to a half-hour apiece, played in the street without amplification. It’s dusty, rowdy work, the karindula player plucking and bashing away on his giant banjo and the vocalists, sometimes in conjunction with the crowds of young children watching, layering complex vocal interplays over the top. The shrill ululations of the female spectators punctuate the proceedings with ecstatic abandon. British playwright, singer and broadcaster Kwame Kwei-Armah has spoken eloquently of how West Indian reggae is anchored around the heavy bass sound, this being a blood folk memory of the low-register creaking and groaning heard by the captives in the holds of the slave ships, as distinct from the more treble-oriented nature of the African music they were forced to leave behind. Certainly karindula is upper-register heavy, but no less rhythmic nor dance-friendly because of it. Bana Lupemba’s magnificent “Kiyongo,” clocking in just short of a hefty eighteen minutes, mixes furious ass-shaking with a snaking, weaving vocal, massed audience participation and lyrics which translate as “Whose hen is this? It’s Kabibi’s because it has no hair.” The DVD, filmed by Kenis, features the visual record of these low-key yet riotous performances by BBK, Bana Simba, Bana Ngoma and Bana Lupemba. In front of several hundred people, including a large number of children aged between two and 12, the bands run through their repertoires whilst members of the audience, or sometimes even the band themselves, give impromptu performances in exchange for a few notes shoved into their garments; a young lad of around 12 gives an incredible performance with an old tubeless bicycle wheel spinning on his head; a man performs a near limbo with a glass bottle of water sticking to his forehead like Velcro; there are liberal doses of pan-gender and pan-generational booty shaking; one of the singers picks up a large clay urn in his teeth whilst another man dances on his shoulders; for an encore the same man picks up the karindula player himself with his teeth. Even one of the more mature ladies in the audience gets in on the action and decides to booty shake. It’s hard to imagine her British counterpart in the Godalming W.I. doing quite such a memorable turn on the dance floor. Bana Ngoma’s karindula player channels the spirit of Hendrix and plays a passage of the song using his foot instead of his hand. Hell, he’s sitting on and playing a giant banjo, so why not? One moment definitely not for the squeamish, however, occurs during Bana Lupemba’s “Kiyongo,” as a man who has just put out his, ahem, cigarette, promptly proceeds to carve open his tongue with a razor-blade and insert a large feather-tipped skewer into his cheek. It’s a moment of pure, transcendental excess where the ghost of Georges Bataille looks on approvingly – but don’t try this one at home kids.The Karindula Sessions is much-needed window into the deeper world of Congolese music. Most of us will never, sadly, make it to Congo’s Copperbelt mining towns to the see karindula played in situ, but, thanks to Kenis, this really is the next best thing.

-David Solomons-