Listening to Cluster’s debut album Cluster 71 is like wandering around the British Museum’s Mesopotamia room and being floored by the fact that this civilization flourished when most of the world still lived in caves. The reissue’s subtly amended title reinforces the startling fact that the album was released at a time when the world was actually listening to James Taylor and Carole King records. Like the Mesopotamians before them, Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius had arrived at the party far too early. A decade later and Cluster’s grinding feedback loops and churning dissonance would have sat them comfortably at the head of the industrial scene, but it would be another seven years before the remarkably similar Second Annual Report arrived, and seven years was a long and lonely time back in the seventies.

The pair had already released three albums with Conrad Schnitzler as Kluster by this point, but they were very much rooted in the world of the avant-garde, full of sonic adventure, but somehow missing the heartbeat that pervades their debut as a duo. There are no actual rhythm instruments used here, but the crossplay of delay units and oscillators establish a throbbing pulse that shifts the music into the rock world, albeit a very distant outpost of that world. There’s even a fleeting moment during the second of the album’s three pieces when a nascent house rhythm emerges, before the duo think better of jumping a further ten years into the future and decide to leave that for another day.Julian Cope omitted this record from his influential Krautrocksampler Top 50 on the grounds that it was impossible to find, replacing it with its slightly lesser follow-up. Happily, the wonderful people at Bureau B have righted that problem and this true milestone in electronic music is now accessible (and indeed essential) for all.

We then leapfrog Cluster’s more widely known mid-70s period and the collaborations with Michael Rother in Harmonia and with Brian Eno which are already available and arrive at some semi-forgotten solo treasures from the late 70s and early 80s.When I saw Cluster playing live last year, the enduring impression was that of watching two grand masters playing chess. Facing each other across a shared table, each carefully responded to the other with the effortless rapport of 40 years’ collaboration. That rare chemistry suggests that Cluster ought to be far greater than the sum of its parts, but these offshoot and solo projects would seem to contradict that assumption.

As a broad generalization, Roedelius’ solo work is the more melodic with Moebius being more locked into rhythm, but neither are lacking in balance. More striking is both men’s alchemical mastery of individual tonal palettes and textures that free them from sonic fashion tyranny; none of these releases sound at all dated and are just as divorced from their respective period as that classic debut.

As a broad generalization, Roedelius’ solo work is the more melodic with Moebius being more locked into rhythm, but neither are lacking in balance. More striking is both men’s alchemical mastery of individual tonal palettes and textures that free them from sonic fashion tyranny; none of these releases sound at all dated and are just as divorced from their respective period as that classic debut.

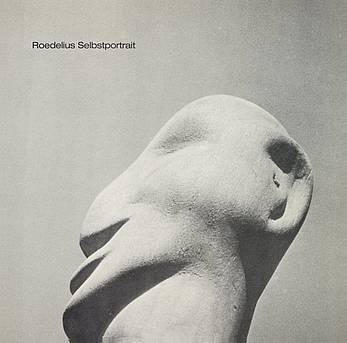

For his solo work, Roedelius turned his back on the uncompromising modernism of early Cluster and harked back to the rich heritage of German romantic music, ingeniously stripping it of negative historical associations by presenting his deeply melodic motifs in a rigorously minimalist and concise setting that allowed no space for sentiment or pomposity.

Released in 1979 and 1980 respectively, Selbstportrait I and II comprise home recordings made as far back as 1973 using mostly a Farfisa organ with various treatments. Had they been released five years earlier, they would have taken much of the thunder from Eno’s much lauded innovations in minimal instrumental and ambient music. On a recent BBC documentary on Krautrock, Cluster pointed out that Eno came to learn from them and not vice versa, and nowhere is this more evident than on these early Roedelius solo releases. To be fair though, these recordings are too melodically interesting to be truly ‘ambient’ by Eno’s definition of a music that could be equally listened to or ignored. By 1984’s Geschenk des Augenblicks, Roedelius had not only abandoned dissonance, but also (temporarily) electronics, and gave us an album of melodic miniatures with traditional instrumentation, Roedelius’ grand piano augmented by cello, woodwind and even guitar. It’s testimony to the man’s melodic mastery and taste that the album manages to steer clear of the superficially similar but vacuous new age movement that was emerging at around that time. Happily, the record sits more comfortably alongside Popol Vuh’s great Werner Herzog soundtracks than the new age ninnies.

By 1984’s Geschenk des Augenblicks, Roedelius had not only abandoned dissonance, but also (temporarily) electronics, and gave us an album of melodic miniatures with traditional instrumentation, Roedelius’ grand piano augmented by cello, woodwind and even guitar. It’s testimony to the man’s melodic mastery and taste that the album manages to steer clear of the superficially similar but vacuous new age movement that was emerging at around that time. Happily, the record sits more comfortably alongside Popol Vuh’s great Werner Herzog soundtracks than the new age ninnies.

Moebius, although less prolific in his solo output, stayed truer to the futuristic vision of Cluster with albums that effectively explored avenues that led on from the group’s influential 1974 album Zuckerzeit. Both his soundtrack to the film Blue Moon and his follow up Tonspuren are full of quirky and awkward sounds and rhythms, a bit like The Flying Lizards without the tiresome post-modern irony and with even a hint of The Residents surfacing from time to time.

Moebius, although less prolific in his solo output, stayed truer to the futuristic vision of Cluster with albums that effectively explored avenues that led on from the group’s influential 1974 album Zuckerzeit. Both his soundtrack to the film Blue Moon and his follow up Tonspuren are full of quirky and awkward sounds and rhythms, a bit like The Flying Lizards without the tiresome post-modern irony and with even a hint of The Residents surfacing from time to time.

The real unearthed treasure though, is a pair of collaborative albums that Moebius made with the bass player Gerd Beerbohm in the early 80s. Nobody seems to know what Beerbohm did either before or after these two albums, which is a great shame, as the evidence here is that the duo possessed a chemistry equal to Cluster themselves. 1982’s Strange Music comes in a sleeve that suggests Adam & the Ants but the music within is an urgent dub-driven post-punk that could sit happily with Public Image Ltd or The Pop Group. Beerbohm’s bass providing a perfect foundation for Moebius’s electronic explorations, being reminiscent of Jah Wobble and his Krautrock excursions with Jaki Liebezeit and Holger Czukay. Moebius may (temporarily) no longer have been 10 years ahead of his time, but he still sounded utterly modern, something that could not be said of many of his contemporaries in 1982.

The real unearthed treasure though, is a pair of collaborative albums that Moebius made with the bass player Gerd Beerbohm in the early 80s. Nobody seems to know what Beerbohm did either before or after these two albums, which is a great shame, as the evidence here is that the duo possessed a chemistry equal to Cluster themselves. 1982’s Strange Music comes in a sleeve that suggests Adam & the Ants but the music within is an urgent dub-driven post-punk that could sit happily with Public Image Ltd or The Pop Group. Beerbohm’s bass providing a perfect foundation for Moebius’s electronic explorations, being reminiscent of Jah Wobble and his Krautrock excursions with Jaki Liebezeit and Holger Czukay. Moebius may (temporarily) no longer have been 10 years ahead of his time, but he still sounded utterly modern, something that could not be said of many of his contemporaries in 1982.

All these records are worthy of your investment, but Cluster 71 is absolutely essential, with the two Moebius & Beerbohm records and Roedelius’ Selbstportrait following closely behind. As if this lot wasn’t enough, next on Bureau B’s agenda seems to be the debut release from Roedelius’ new duo Qluster! I can’t wait!

-Alan Holmes-