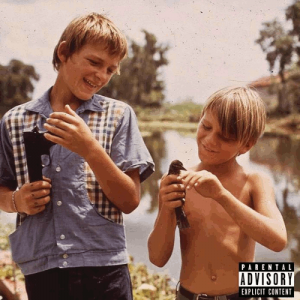

Columbine are a group of rappers from Rennes who have captured the spirit of French adolescence. They have recently released their third album, Adieu Bientôt, and are blooming into a rather well-known band. They describe themselves as “absurd, naive and deep” and their music mixes synths and guitars to create their own universe.

Columbine are a group of rappers from Rennes who have captured the spirit of French adolescence. They have recently released their third album, Adieu Bientôt, and are blooming into a rather well-known band. They describe themselves as “absurd, naive and deep” and their music mixes synths and guitars to create their own universe.

Through a plethora of lyrics, they have really captured the imaginations of many teens who have felt pushed to the side. They’re a band that takes a few listens to actually get into, and many more listens sometimes just to notice a single phrase through the density of their lyrics. They haven’t hit the mainstream yet, but they’re not entirely underground either.

Their music isn’t for everyone, and is far from being the conventional radio music most of France is used to these days. They kind of make their own genre; and yes they are a rap band, but it’s not 100% hip-hop. They’re more than just another rude band of wannabe thugs, although they will use that imagery and put a comedic spin on it. Alternative rap? Cloud rap? Maybe. Maybe not. Here’s Columbine, high school friends who joined their strengths together to rise from no-one else’s ashes.

Just the name Columbine will catch your attention, and their already iconic bird/rifle logo is plastered over many kids’ chests on sweatshirts around the country, on every street and even in pictures of rebelling lycéen.ne.s during the recent unrest outside high schools all over France. Columbine attract kids similar to themselves, les enfants terribles (also the title of their second LP), although their audience is ever-growing. Current political events almost seem like they could have Columbine as a soundtrack to the riots and protests happening across France, which almost seemed predicted, perhaps even desired, in “Remi”, “Cache-Cache” and especially “Brûler”.

At first, there was a bit of a humorous side to some of the songs on their first album, Clubbing For Columbine, especially in “2k17” and “Dom Perignon”, although they did show a bit of darkness in a few tracks. Things got a bit darker still on Enfants Terribles, with the title track, “Les Chaméleons”, “College Rules” and “Château de Sable” having a certain noirceur about them, but with a twist on childhood, with many references to early teens and school ages as well as what could be their own future children. Parents are also omnipresent throughout the album. Childhood is another recurring theme in Adieu Bientôt, in “Cache-Cache” and “Biographie”, which features Foda C’s younger sister’s voices alongside his own. It’s quite a slow, gentle track just about home life, and you can hear them just going about their daily business. It’s a nice song that seems quite positive in contrast to other pieces about their personal lives and childhood, which are often rather negative and dark.

On Adieu Bientôt there’s a more twisted side in other tracks, notably “Bart Simpson”, where Lujipeka describes having “Parkinson’s on the trigger”, presumably of a gun. But that’s far from the only mention of violence. “Indochine” and “Brûler” both reference fire, the former creating an image of orgasmic pleasure that has become bland and routine, and Luji seems to be contemplating immolating the poor girl featured in the song; but in “Brûler” it takes another turn, and they just want to burn everything, almost in a call for a revolution.

One of the best things about them is their lyrics, which always seem almost laid-back and random, but at the same time calculated, using their rich language to its full extent. They also use a fair amount of English, such as in “Stockholm” and “Virgin Suicide” (which almost has a comedic element with the pronunciation of “suicide” as soocide, whether that is intentional or not). There is also an interesting use of English as slang (as is often done by French youths) across all their albums, with words like “cash” (with its double meaning on “Cache-Cache”), “high” and “bad mood”, and in many song titles such as “Topless”, “Teen Spirit”, “Talkie Walkie” or “Fireworks”. And of course there will always be the iconic Spanish lyric “Gracias por la muerte” in “Les Prelis” from their début album.On this album in particular, guitars often accompany the group, giving a grungier side to some tracks, but synths still prevail. In “Pierre Feille Papier Ciseaux” (“Rock Paper Scissors”) they say “he’s not afraid of auto tune”, and they certainly aren’t, maybe even using it a bit too much at times. In a way, just hearing their music over headphones is quite calming, but it’s easy, good listening with plenty to think about and profit from the never-ending lyrics. But then, as I discovered at their 7 December 2018 concert in Istres, that music can become a crowd-pumping mass of heavy, chant-along anthems.

Lujipeka and Foda C ruled the stage, accompanied by Chaman, Chaps and Sully, as well as Luji’s younger brother Tom and their DJ. The group delivered a well-organised but still liberating performance of Adieu Bientôt as well as some other songs from Clubbing For Columbine and Enfants Terribles. There was a certain theatricality to their gig performance, especially from Foda, who almost acted out his lyrics in certain songs, and captivated the crowd with his commanding charisma. It’s also impressive the sheer amount of lyrics that they can recite flawlessly. A few of the songs from their latest album didn’t appeal to me too much, but this gig rather changed my mind, so maybe it’s just the memories that go with them now. It’s a bit odd in a way, and shows just how different the studio and live versions can be, even if they’re of the same track.

A recurring theme, particularly across the last two albums, is the image of a storm, often associated with a girl, who is in the storm or is the storm. “Âge D’or” is something of a reflection on themselves, graced by the almost unexpectedly melodic voice of Foda that we’re not so used to, despite his obvious vocal prowess. It’s another glimpse into his perspective of how the rock star life has changed them, as well as just being a regular person with regular issues, and scattered with references to other lyrics from other songs. It almost seems resentful of his own way of life that seems to be doubled. It ends with a recorded voice of Foda just talking, reflecting on it all. The natural spoken word is something that is not unknown in Columbine tracks, and it’s often part of my favourite bits of their records, recalling tracks from other albums, such as “Mode Avion”, “L’école” and “Mandragore”.

I never thought I would ever get into any French music, let alone hip-hop or rap, but Columbine proved me wrong. Sure, they are a hip-hop, kinda cloud rap band, but they mix sprinkles of other genres into their music. Their charisma and way with words have captivated me and many others. They’re a band for outsiders, but without being exclusive in any way. Columbine put out their music and just let it land anywhere. Their audience ranges from kids who just like their sounds to teens who found themselves in their music and are forever attached to them. They are very much an adolescent band, barely being past adolescence themselves, and by making music that brings teens to them in droves. Columbine are just really getting into it, having only been around for four years, and with just three albums under their belts they still have much more room to grow. There’s no doubt that they’re going places, where I hope that I and many others will follow them faithfully.

Columbine’s power isn’t drawn from guns as their name might suggest, it’s in words. They’re not just made of stories and metaphors, but words that feel like real life.

-Words: Frankie Harmonia-

-Live photo: Zélie Freijo-