Conny Plank and his circle were, as record producer David M Allen says: “The hippies who fell in love with machines”.

Conny Plank and his circle were, as record producer David M Allen says: “The hippies who fell in love with machines”.

*

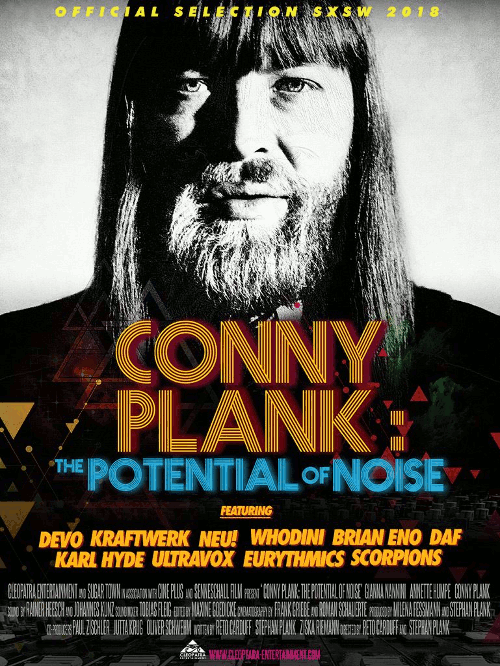

Much has been said about how the youth of Germany needed to reinvent themselves – and their art – at the end of the Second World War. Distancing themselves as quickly as they could from their parents’ generation, some found inspiration in “ethnic” music (Can), meditational South American ritual (Popol Vuh) and some in space (Cosmic Jokers, Tangerine Dream).

But one man set out to actually invent something completely and genuinely new. His timing was perfect. From a musical family, trained at a radio station and an accomplished recording engineer, he set up a cutting-edge studio in Wolperath in rural Germany with his family in 1973.Against a background of international counterculture, money was something that “passes through, just like my tapes pass through”, “we have a different concept of capital”, “different from big business”, Conny says in this wonderful, colourful documentary. This ethos coincided with Plank’s fierce enthusiasm for the upcoming bands he chose to work with: he would often contribute financially to recording bands he believed in: NEU! and Cluster, for example. And those he didn’t: “I cannot work with this singer” he famously said of U2‘s Bono, having been chosen to produce their record The Joshua Tree. Similarly with The Cars.

This enthusiasm – he would “rev up” the bands, according to Scorpions — meant that the bands felt welcome, encouraged, driven to explore their own creativity and their own sound by this huge man who espoused the ethos that “craziness is holy”. “He didn’t really have a sound”, says Mute Records‘ Daniel Miller. “The bands sounded like the bands”.

“We were moved by the times and wanted to make relevant music, not commercial music” explains Hans-Joachim Roedelius of Cluster and Harmonia. “Whatever was acceptable in society had to be challenged”, says Michael Rother (Kraftwerk, NEU! and Harmonia). “That included dress codes. And dealing with intoxicants”. Roedelius has said that upon walking into his studio, you’d hit “a wall of smoke — of all kinds”.

International counterculture pivoted around many centres: in Germany, Plank’s country retreat was the place to be: “…politically, he was a revolutionary, musically he was absolutely a revolutionary.” (Jaz Coleman, Killing Joke). Gerald Casale of DEVO recalls that Brian Eno added synth melodies to their recordings at Conny’s studio to make them more palatable, prettier. DEVO’s stance at the time was strictly “anti-melody”. Conny understood that and didn’t use them in his mixes: he was a selfless “enabler”, as music journalist David Stubbs notes. Plank said he functioned “as a medium between the artist and the tape: what’s their state of mind, which I have to transfer.” Interestingly, these tapes have recently been rediscovered, featuring these synth parts and vocals by Eno and David Bowie.

Hip-hop legends Whodini, in the “early days of hiphop”, at 17 years old, having never been out of New York City, suddenly found themselves in Wolperath. Jalil says that, as a rookie, he felt uncomfortable singing into a mic in the studio. Plank rigged up a system whereby Jalil could sit outside in the park and record. “Excuse me for getting emotional”, he says, “nobody’s ever took that time for me like that”. After the huge international success of “Vienna”, Ultravox moved to his studio for three months with no ideas at all, intent on experimenting with the master. Midge Ure: “We wouldn’t have tried that with anyone else but Conny“.And what a list of artists: NEU!, Kraftwerk, Cluster, DEVO, Brian Eno, Killing Joke, Harmonia, Freur (later called Underworld), DAF, Eurythmics, Ultravox – a diverse spread of styles, but they all have a thread of inventiveness. And the consistency of his production — clear, tight, edgy, energetic, technically faultless — with a joyous yearning for modernity. An escape from the turgid, stale old ideas of the past – never over-produced to flat perfection — there is always something surprising in a Conny Plank production.

An early tutor at the radio station they both worked at, Wolfgang Hirschmann, says that he knew talent when he saw it. An early supporter, he saw Conny work tirelessly day and night, but his wife Christa was the key to the operation running smoothly. She was “just as important as Conny. She just had a different section”, he says. The film deals with the matter that Conny, with his furious work schedule, had little time with his family and son: “You were Christa’s son’, says Can’s Holger Czukay to Stefan Plank, Conny’s son and co-director of this film. Annette Humpe remarks that Conny was “not the perfect father”.There is a touching section where Stefan and his family visit the site where Conny’s studio, closed since Christa’s death in 2006, once was: and you get a real sense of what Robert Görl (DAF) says: “As soon as you were there you became part of the family”. Their kitchen table has been described as ‘the centre of krautrock’, a place where ideas were generated and then tried out in the studio.

Conny died in 1987, his legacy a testament to his genius: the music he produced and made himself — the proto-techno of his work with Dieter Moebius, for example – DAF, Kraftwerk, Lilienthal, Kluster — torched a completely new path away from blues-influenced rock ‘n’ roll into the twentieth century and beyond. His huge, benevolent, nurturing shadow looms over all modern music.This is a great, classy, stylish music documentary: the artists are allowed to speak at length about their cherished memories, there are plenty of old photos and some great old footage and crucially, unlike many docus, you get to hear fair sections of the music. And do the machines get to speak? Sure they do: there is just enough techie info to get your geek on / off. An inventor at heart, Plank developed a system whereby a Polaroid could be taken of complex mixes on the studio’s mixer and projected back onto the mixer at a later date, pre-empting SSL’s Total Recall system by years.

Close-up, you see and hear the tape wound onto the machine in almost perverse ASMR detail (the audio in this film is, as you’d expect, excellent), the play button is pressed and DAF’s “Der Mussolini” lives again, direct from the master tape. It’s worth watching this film for that clip alone. You get to see original tracksheets, close-ups of his desk, photos of almost all of the bands in the studio and clips from relevant videos. You see Conny’s famous custom Zähl mixing desk removed and entrusted to the safe hands of David M Allen.Pacey, and packed with great stories, choice quotes and fantastic music, you will want to watch this docu repeatedly. In one section, a louche and well-oiled Dave Stewart pinpoints his musical capitals of the world: “Kingston, Havana, Liverpool, Wolperath”.

*

And the machines loved them back.

-Leon Muraglia-