In the great taxonomy of rock, Alan Vega was kind of like a platypus. ‘What? That can’t exist in nature!’ A Catholic Jew (a combo not known for its over-frequent presence in demographic cross-breaks), a veritable Methuselah when punk broke (he was already forty, though pretended to be a decade younger) and a pioneer of the electronic sound when all around was guitars, one would struggle to really believe it if it weren’t all completely true.

In the great taxonomy of rock, Alan Vega was kind of like a platypus. ‘What? That can’t exist in nature!’ A Catholic Jew (a combo not known for its over-frequent presence in demographic cross-breaks), a veritable Methuselah when punk broke (he was already forty, though pretended to be a decade younger) and a pioneer of the electronic sound when all around was guitars, one would struggle to really believe it if it weren’t all completely true.

Young(ish) Alan Bermowitz, a lifelong devotee of rockabilly music and comic books, had been gifted a second epiphany (he had already seen Elvis on the Ed Sullivan Show in the Fifties) when he witnessed a Stooges show at The Pavilion in Flushing Meadow in the summer of 1969. Inspired by Iggy Pop’s on-stage antics, Alan Suicide (as he was then sometimes known, taking the name from his favourite Ghost Rider comic entitled Satan Suicide) was then creating light sculptures built from “half-broken TV sets, stolen fluorescent tubes, chains, subway lights, broken glass and other bits of detritus [he] picked up from the streets” and making far-flung electronic experiments at the Museum: Project of Living Artists, a twenty-four-hour downtown workshop / performance art space at 729 Broadway, publicly funded by the New York State Council on the Arts.

Serendipity soon intervened, a night of filthy weather forcing passer-by Martin Reverby, musical obsessive and former pupil of jazz bebop legend Lenny Trisanto, to duck into the space in order to avoid a soaking outside. What Rev discovered there was Vega and fellow artist Paul Liebegott summoning dissonant electronic noise and feedback from a guitar and some speakers. Unexpected though it was, Reverby recognised a pleasantly nasty noise when he heard one, and proceeded to lock into the vibe immediately, picking up some rusty industrial springs that were lying discarded nearby and beginning to pound out an accompanying rhythm by banging them against the floor. Although it would necessitate negotiating a few bumps in the road before it crystalised properly, the powerful association between the two men – both musical and personal – would eventually burst forth as the exotic bloom of Suicide, their idiosyncratic career giving the world a clutch of incredible recordings, and another great American frontman for its pantheon of alternative rock. Vega’s particular place in that array of icons can best be gleaned from Dee Dee Ramone’s 1990s biography Poison Heart: Surviving the Ramones, wherein he remarks:When I first saw Alan Vega and Suicide, I pulled out my 007 knife and palmed it behind my wrist. To be frank, I was a little worried. If Iggy had created a Frankenstein, it was Alan Vega. When Alan jumped into the sparse audience, it was a bit too much for me. I didn’t know what was going to happen. He [was] a very serious performer.

Sadly, Vega passed away (peacefully) in 2016, finally silencing one of the most distinctive artistic voices in modern American music and the visual arts.

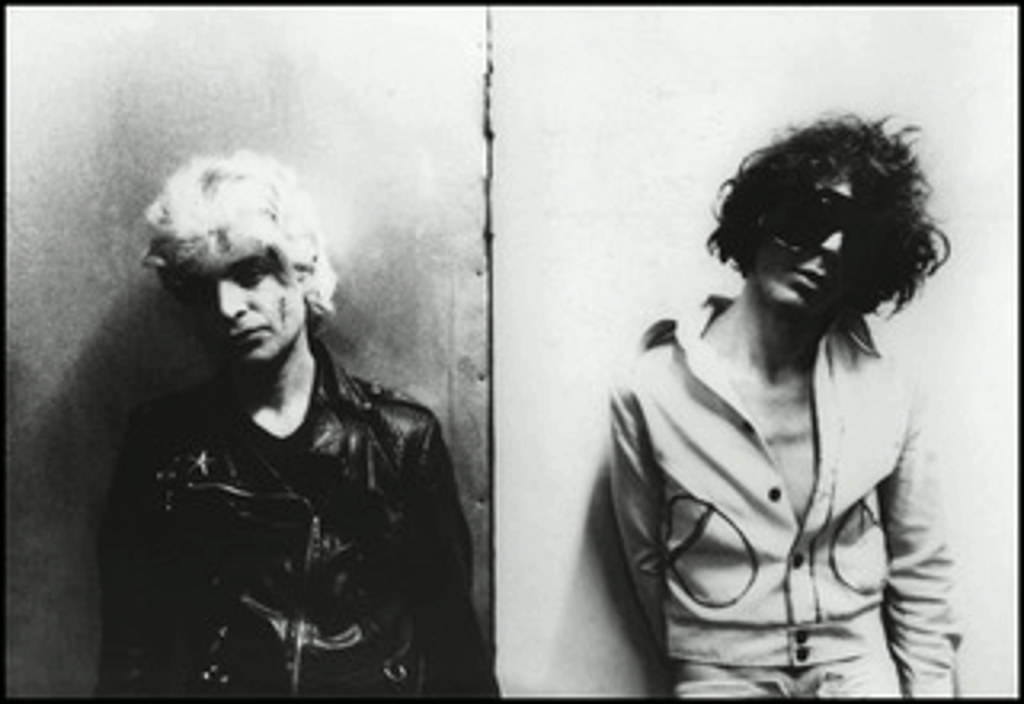

It comes as something of a pleasant surprise then that, five years after his death, Sacred Bones have begun the not-inconsiderable task of collating the best of the Vega archives (or Vega Vault as it was termed), now issuing this volume as Mutator. Recorded in his New York studio in the mid-1990s, the material on the album was apparently something that was unintentionally buried in the flurry of activity in which Vega was engaged at the time, a particularly fertile period in which he had been energised by a variety of contemporary sounds: New York’s vibrant hip-hop scene, the new wave of emerging ambient and electronics, and the avant-garde sensibilities which had always been present in his work. Uncovered in 2019 by Vega’s friend and collaborator Jared Artaud, the master recordings made by Vega and his wife and long-time musical collaborator Liz Lamere have finally now been properly mixed and mastered. At a lean thirty-two minutes in duration – with a shadowy Vega peering from the darkness of the cover shot like the ghost of a face on a late nineteenth century postcard – the sound of the album is muscular, Vega foregrounding some of the more rockabilly undertones that were always present in his voice, a drum machine holding down a variety of simple beats in a Dr Avalanche style, and the production clean and crisp. Lamere recalls: “I was playing the machines with Alan manipulating sounds. I played riffs while Alan morphed the sounds being channelled through the machines.”The proceedings are kicked off by “Trinity”, a short, dark mass, an unsettling incantation which feels like an alternative soundtrack for the unforgettable scene in Beneath The Planet Of The Apes in which the cowled mutants worship the still-functional Alpha-Omega bomb: “The Heavens declare the glory of the bomb, and the firmament showeth his handiwork.” And in case that seems like reaching somewhat, well, the first successful test of the atomic bomb at Alamogordo in New Mexico on 16 July 1945 was known as the Trinity Test.

“Fist” and “Muscles” both pound with a relentless, at times almost oppressive, energy, their atmospheres lying adjacent to the kind of Nineties industrial sound which Suicide had done so much to help evolve in the first place. “Samurai” is much lighter and airier, verging at times on the kind of signature dreampop which David Lynch and Angelo Badalamenti had recently developed for the global smash hit Twin Peaks. One wonders how Laura Palmer’s story might have been affected if it had been Alan Vega crooning her soundtrack rather than Julee Cruise. At the very least, it is easy to picture him in one of the end-credit musical appearances that characterised Series 3. “Filthy” is a swirling mass of background electronica, the drum machine beating along mercilessly like a Roman galley, while “Nike Soldier” is an album high point, a slow toe-tapper akin to some of Depeche Mode’s darker musings, Vega’s distinctive whoops, growls and hums animating the airless rhythm. The near-instrumental “Psalm 68” edges into profoundly Coil territory, raising an interesting mental experiment of imagining Vega and Jhonn Balance singing it as some kind of duet. The last of the eight songs, “Breathe”, has a more ambient quality, in the post-Brian Eno sense, Vega’s narrative evoking everything from Jesus to video screens as the album drifts away rather than coming to a profound full stop.Mutator, far from being a scrabble round the back of the cupboard, is actually an excellent album, and one whose depths are increasingly obvious with every subsequent listen. “Fist” in particular is an old-fashioned grower, with a nagging hook that stays in the brain long after the song has finished playing. It may have been a shame that the album was so unwittingly shelved back when its creators were quickly focussed elsewhere, but it still sounds fresh and relevant even the best part of thirty years later.

Some half-decade after Vega passed into the great rock and roll Valhalla, it’s no trifling matter to have such a great reminder of why there was a space reserved for him there in the first place.-David Solomons-