Freq talks to Simeon Coxe of Silver Apples

Eastern Bloc Records, Manchester, 1988.

Quietly, amidst the bursting green shoots of the newly emergent dance music culture, Suicide have just released the magnificent A Way of Life, their first new album in eight years. It may as well have been 80 years, so long ago does 1980 now seem. A callow 20-year old, I am queuing in Eastern Bloc Records – at that time teetering on the cusp of its time as arguably the hippest record ship in the UK – clutching a fresh vinyl copy in one hand, and some specially-withdrawn bank notes in the other.

The shop’s owner Martin Price, a prime mover behind local heroes 808 State, was justifiably famed for the often scathing judgements he would pass on buyer’s purchases when serving them at the counter. Many an embarrassed punter slunk out of the shop, emasculated and with their tail between their legs, after being publicly rebuked for the quality of their purchase with a curt, but effective, “That’s shit.” It was a curious business model, but one he pursued determinedly.

Nervously, I place A Way of Life down on the counter and, as the monetary transaction is taking place, the comment that comes my way is not the withering fusillade expected from Price, but instead an interjection from a guy seemingly doing nothing more productive than hanging around at the counter – not a member of staff, but a fellow punter. He seems hugely old (all of about 40), and he nods approval at my purchase, adding with a drawl, “Hey, if you like Suicide, you should check out Silver Apples.” I mumble back a well thought-through rejoinder such as “Yeah. Cool man,” before sloping out of the shop.

It might all so easily have soon been forgotten by the end of the journey home, yet there was something about the name that had stuck, its Yeatsian provenance nagging insistently at the back of my mind. Silver Apples. Silver Apples. Seized by its lunar resonance, a quest soon began, an epic worthy of Chrétien de Troyes’ Grail Romances, as I hunted across the arid lands of pre-CD, pre-Internet Albion for the hallowed grooves of Silver Apples. And it was a quest I had to undertake alone, for no man – or woman – was to help me. No-one knew anything about Silver Apples, no-one could really tell me much about them, nor point me towards a way that I might at least hear them. Yet I was fired with the righteousness of my cause, and the quest continued: record shops were scoured, knowledgeable elders were consulted, record fairs were picked apart rack by tedious rack. If there had been a jagged cliff above crashing waves, I would have stood atop it and yelled “Lord, why have you forsaken me?” into the howling gale.The 1980s gradually turned into the 1990s. The Berlin Wall came crashing down, taking with it many of the certainties of the post-war era. In 1992 Suicide released another album, the largely (and justly) forgotten YB Blue. After half a decade, the search had slowed to almost nothing, lost as I was like Lancelot, mad and wandering the wilderness following his banishment by Guinevere. Surely this was a fool’s errand? I had wasted all that time and emotional energy on, at best, the chance ramblings of a madman, at worst on a malicious attempt to deceive.

And then it happened. A miracle. In 1994, German label TRC issued a Silver Apples CD, collating their two albums – Silver Apples from 1968 and Contact from 1969 – onto one disc. No longer was I Lancelot, perfidious and cursed, but instead his son Galahad, whose purity of heart had finally allowed me access to this Grail. On the bus home from Selectadisc Records, I was at last holding it there in my hands.

After a quest so long it felt wrong to simply go to my room and play it on the stereo. There needed to be some sort of fanfare, a glorious celebration of success, a rousing introduction to the inaugural play. It was a truly glorious summer afternoon, so, grabbing my girlfriend’s Sony Discman, I hopped onto my bike and cycled swiftly towards Highgate. Why Highgate I wasn’t sure, except that it was at altitude and had a nice park. Somehow, altitude seemed important when hearing Silver Apples for the first time.Hot and tired I sat down on the grass in Waterlow Park and drank some cool water. It was like nectar. But then, a terrible uncertainty descended over me. After all these years, I was finally about to listen to Silver Apples. Yet what if it wasn’t any good? Up until now I had been so absorbed in the mechanics of the quest that I had not even stopped to think about whether it would be worth the wait.

I put on the headphone, lay back on the grass and pressed ‘Play’…

*

Freq: In the period before Silver Apples, can you tell me about moving from New Orleans to New York in the mid 1960s?

Simeon Coxe: It wasn’t due to music at all. I wanted to be a famous artist and at the time, New York was the happening scene as far as I was concerned. People like Robert Rauschenberg, Jasper Johns and those guys were making waves, doing new and inventive art, and I just wanted to be a part of it. So I left school in New Orleans, left home and caught a train to New York. I arrived at Grand Central Station with $25 in my pocket, I didn’t know a soul, I just took it from there – you can do that sort of thing when you’re 19 years old. It doesn’t matter because you can sleep on a bench for a while.I tried to find coffee houses and bars where artists were hanging out, and I met them, and talked with them, and eventually got myself a job and got started on a painting career. And I found that there were about 5,000 other people from all over the United States that were trying to do the same thing, and it was a lot rougher than for some guy from New Orleans to go to New York and crack that. I went from feeling hugely confident to feeling hugely scared. But I did find work down in The Village as a carpenter, I had some carpentry skills, and I eventually started sitting in with bands, just more for a lark than anything else, playing tambourine, singing back-up and passing the hat. I even started to make a little bit of money as a musician, just on the side.

What sort of music were you involved in?

It was folky, jazzy, that kind of thing. Nothing rock. More like a jugband kind of a feel. I played washboard, I even picked up a jug and started learning how to play that. I could play some nasty bass licks on the jug…

I took a job as a dishwasher in a ski camp up in Connecticut one winter, and the guys who worked the tables and worked in the kitchen and washed the dishes were bluegrass musicians. They used to sit out on the back porch of the dining hall in between meals and play bluegrass, so I kind of fell in with that. I started singing back-up, I mean I have sort of a bluegrass background being from the South, so it was a natural feel for me. I got into the music, and that group of bus boys and waiters and bartenders gradually became The Random Concept. We eventually got amps, an electric guitar and a set of drums and started working gigs in the local area. Eventually we got quite a name for ourselves. This is between about 1963 and 1965, possibly pushing on into 1966 aways.

The Random Concept became quite a phenomenon up in Connecticut and in the New York club scene. We got a booking agent and started playing clubs in New York and living in hotels down there as a band, you know, everyone piled into a couple of rooms, that kind of living. We were in the Albert Hotel along with The Mothers of Invention, The Blues Magoos, The Lovin’ Spoonful and tons of other bands that were playing the same places that we were. We all got to know each other. It was that kind of a scene. And it was through that scene that I eventually got a job singing with The Overland Stage Band, that had Danny Taylor as the drummer. That’s how I met Danny, in the Greenwich Village scene of the mid 1960s.

What were The Overland Stage Band like?

The Overland Stage was strictly covers – they didn’t have one, single original tune. I kept pushing for them to write material, as I had written lots of songs with The Random Concept, we played lots of original material. Many of our most requested numbers were original material as opposed to covers of The Beatles or The Rolling Stones, all the things that you had to play in order to get gigs. But The Overland Stage just weren’t interested, even though I kept showing them songs that I had written for The Random Concept and saying “Look, here are ready-made songs, let’s do it, it’s popular.” No, they weren’t interested.So that was the kind of mental attitude when I broke an oscillator out and started playing it on stage with them – you can imagine the hostility.

Why on Earth did you start playing an oscillator?

Well, we were the house band at the Café Wha? That meant we played four sets a night. You just run out of material – there’s not enough material in any band’s repertoire to cover four sets. And so what they would do, towards the end of the evening, rather than start to repeat themselves, they would play these long, endless guitar improvisational blues jams. So as a singer, I got nothing to do! I’m just standing there, trying to look interested. I was very awkward, and I didn’t feel good doing that, so one time I brought an oscillator up onstage just to give me something to do and, started making all kinds of beeps and whoo-whoo sounds. I tried to play along with them, as I had done that before in my apartment, playing along with records, and I liked it. One night onstage I plugged into my PA amp and started doing it.

The band absolutely hated it, but they had to sort of go along with it because the manager of the Café Wha? thought it was the best thing he’d ever heard. He’d said he was going to fire us because we were getting repetitious and people weren’t staying, but once he heard [the oscillator] he said he’d keep us on. That made it even worse among the personnel in the band, they really didn’t like it. One by one they drifted off and found other gigs and other bands that were more conventional. Then one day it was just me and Danny sitting there looking at each other. We said “What are we going to do?” We decided, on the encouragement of a guy called Barry Bryant, who was an artist. He said he would put us up in his art studio and let us rehearse if we would develop some kind of a sound with just the oscillators and the drums.So we did that for about six months – we didn’t listen to the radio, we didn’t listen to other bands, we didn’t go out and play music – we just sat in Barry’s studio, Danny with his drum kit and me with my oscillators, and we worked out how to make this thing make music.

Did you have an interest in electronic music before that?

Absolutely none. I had never even heard of some of the people that I now know were contemporaries. I’d never heard of them, or had any interest in them. I was strictly just a rock and roll singer, just a street kid in New York. I had no musical qualifications or electronic engineering skills. I had no idea how that stuff worked.

So where did you get the equipment?

It belonged to a friend of mine named Harold Rogers. He was a composer of what I guess you would call ‘serious music’, Julliard-style music as opposed to pop music. He was a very-forward thinking and avant-garde guy, and he had this oscillator that he had found some place. He used to drink vodka and play his oscillator along with Beethoven and Mozart, get inspired that way, write it all down and then try and get orchestras to accept it. But no-one would pay any more attention to him than they would to anyone else who was playing ‘vodka music’.

One day I was in his apartment, and he was messing around with it. He took a break, and I put on a rock and roll record and started playing the oscillator along with that. From that moment on, I was hooked. I just thought that was the best thing I had heard in a long time, and I was determined to make that work. That’s what inspired me to bring it to the band and plug it in there. I thought that they would be wowed and amazed and thrilled, the same as I was – but all it did was piss them off.What did that six month period initially rehearsing Silver Apples entail?

Well, we didn’t feel like we were doing anything brand new, we were just trying to figure out how to do something with what we had that would be acceptable. We knew we that we wanted to go out and play gigs in front of people, so we knew that for that reason it had to be kind of upbeat and danceable, otherwise people would be bored. And so most of our songs were drum oriented, and because I had no keyboard experience, we weren’t playing anything that resembled a synthesiser or a keyboard of any kind. I was playing push buttons on a piece of plywood, keying in different oscillators.

Eventually, I ran out of fingers, there weren’t enough, so I made a footboard so that I could play bass notes with my feet, one button at a time. My feet, not being trained to do any music either, I was just going ‘boop boop boop boop boop’, just one note after another. Danny found that rather than trying to play a regular backbeat rock and roll sound from his drums to that, it was better to try and play some sort of a repetitive, tribal drumbeat that would complement the rolling bassline, which in today’s language is ‘looped’. What I was doing was looping because I couldn’t do anything else. It wasn’t because I said “Hey, this is a brilliant music concept, let’s do this,” it was because it was all I could do – ‘boop boop boop boop, boop boop boop boop’ over and over and over again with my feet. And so Danny picked up the drums and put a little syncopation in there. He would basically keep the same loop going, and so we built our songs around very, very simple structures like that, very simple melodies. My childhood influence by Fats Domino was a lot to do with that – simple melodies, simple beats, simple song concepts. That was where we went with it, more out of necessity, my limitations, than some brilliant musical idea.So, it seems that those limitations forced you to create something it took the rest of the world decades to catch up with.

Yeah, that seems to have been kind of what happened. I mean we had success with our live music at the time, but we couldn’t seem to make much headway as far as getting major record label support was concerned. We knew we had something because the audiences were reacting very, very well to we were doing.

What kind of venues were you playing live in?

Oh, the standard rock venues, but usually behind big names acts. We played behind Procul Harum, we played behind Jethro Tull, we played behind Blue Cheer, we played behind all the West Coast bands – The Airplane and The Dead – as a sort of a curiosity thing. Our label – Kapp Records – was part of the Decca family, and so they had some promotional money. They got us on these gigs with name bands, the idea being to attract audiences to the stage to see the name band, and then they got to hear us, after which they would go out and buy our records. But what you do when you play for a Grateful Dead audience is that you’re just annoying them if you do something not like them, or is in a completely different ballpark. They haven’t come to hear that. It didn’t really work. Kapp never really understood our audience. They didn’t realise that our audience was much more into a new sound, not the standard old blues-based thing that was going on, and was so popular at the time.Once people got the idea of it being tribal, and danceable, they were on our side. But we never could really get that going. The band eventually went their separate ways not because of the music, but because of legal stuff and things like that.

Where was your first ever gig as Silver Apples?

It was an ‘In the Park’ concert in Central Park in New York. It was highly promoted, an all-day festival, and there were about 15 bands that played that day. We were one of them. The newspaper estimated that there were about 30,000 people in the audience. The first gig! I was absolutely scared to death. I have absolutely no idea what I did. It was a blur. I just remember looking out and seeing a sea of faces. I’d never seen so many people in one place.How did you then get involved with Kapp Records?

During the time that were in that six month ivory tower situation, trying to invent something that was acceptable, that guy I mentioned, Barry Bryant, who owned the apartment, he would go out and go to bars and say “Hey, I’ve got these guys, these weird musicians doing really wild stuff in my apartment. Man, you ought to come and hear them!” He would bring poets up, other musicians, anybody who would listen, and the occasional record company executive, usually some really low level guy who would then tell somebody who would tell somebody. Most of the people who came to see us thought “Jesus, this is just too off the wall,” and they would not respond. The guy from Kapp Records just kept coming back, and kept saying “There is something there. I can’t really put my finger on it, I have no idea if it’s commercially marketable, but there is something going on here, and there is something different.” He eventually talked the people at Kapp, the people in the suits, into doing what started off as a one record deal. But Barry insisted that if we were going to do anything, it had to be two records. It had to be a two record deal. So that is what we ended up with. Fortunately they were hooked up with Decca, and we got that international distribution through Decca Records. It was in fact a major label.

They had absolutely no idea what to do with us. They had artists like Eartha Kitt, but absolutely no rock bands on the label at all. I think one of first things we did on their sponsorship (they put us out to go and play and promote the record), was to play a high school auditorium with The 1910 Fruitgum Company. Do you remember them? They did that song that went “Yummy, yummy, yummy, I’ve got love in my tummy”? That’s the audience they thought was for us.So how did you go down there?

Ah, they were kids, they didn’t care. They came, they squealed, they peed in their pants, you know? But they didn’t buy any records. Kids don’t have any money.

How did the first album get made?

Kapp had a little studio that they use to record Roger Williams and Eartha Kitt and crooners and singers and people that sat at pianos. They had a four track deck and they had an engineer that had never even heard rock music before. He sat down with us and showed us the limitations of the board – what are we going to do? We’ve got a massive drum set and we’ve got oscillators all over the place, plus we want to do vocals, and we only had four tracks! How are we going to do this? He came up with the idea of recording on all four tracks and then bouncing down to one, freeing up three and then bouncing down to two, and then two and then one. So we basically, once we got all four tracks filled up with, say, drums, we would then mix them down without even hearing a bass line to go with it. So it was difficult to get any kind of satisfactory sound qualities.

Kapp had a little studio that they use to record Roger Williams and Eartha Kitt and crooners and singers and people that sat at pianos. They had a four track deck and they had an engineer that had never even heard rock music before. He sat down with us and showed us the limitations of the board – what are we going to do? We’ve got a massive drum set and we’ve got oscillators all over the place, plus we want to do vocals, and we only had four tracks! How are we going to do this? He came up with the idea of recording on all four tracks and then bouncing down to one, freeing up three and then bouncing down to two, and then two and then one. So we basically, once we got all four tracks filled up with, say, drums, we would then mix them down without even hearing a bass line to go with it. So it was difficult to get any kind of satisfactory sound qualities.

It really was not the ideal thing, but it belonged to Kapp Records and they gave us all day, every day. They gave us an engineer and they gave us practically an unlimited amount of time to go in there and do it. They did assign us a producer, but he refused to do it. He felt that if he was connected with us, his reputation as a producer was over. So he faked an illness and went into a hospital and just stayed there. I’m not kidding. I’m not making this up. He faked mononucleosis. He went into the hospital and hid under the covers the entire time we were in studio so that he wouldn’t have to be associated with us.

How long did the first album take to record?

It took a little over a month, about thirty five days. If we had been paying commercial rates it would have cost a fortune. We could not have done it.

What about the second album?

By the time that we were doing the second album, we had already been out on the road promoting the first record. We had a two record contract, and so we started recording the second record when we were out in California, at Decca Studios, where they had a 24-track board. It was a regular size studio, where you could baffle the drums, and you could put different things on different tracks. It was like being in Heaven. The freedom! So we recorded almost the entire of the second record, Contact, on a 24-track board in California. We then took the unfinished material to Apostolic Studios in New York and finished it off there when we got back.

What kind of reaction did you get to the first album when it came out?

It was very mixed. We had already developed a following New York, so we were pretty well received there. Oddly, we had a big following in Cincinnati. In Philadelphia, “Misty Mountain” I think it was, or maybe it was “Whirly Bird”, went into the Top 10 on radio play. But then in California, we couldn’t play a bar, we couldn’t play an empty parking lot. There was just zero response in California. Of course they were promoting their own brand of what they thought music was, the new sound, so they weren’t interested in some New York guys coming up there and doing some weird thing. And in Toronto we had a big audience and a good following. We played behind Jethro Tull and maybe we were attracting just the right sort of people, looking to hear something a little different. We were invited back to the same place in Toronto as headliners within six months. So here and there, there were little hot spots. I remember Minneapolis being another one. We played in the Guthrie Auditorium, which was like the Carnegie Hall of Minneapolis, a sit-down, very formal place, like a theatre. We had them out in aisles, jumping up and down on the leather seats.

Every now and then we’d catch an unexpectedly really good reaction, and other times people would just stand there and stare at us like we were insane. We never knew. Danny and I just did our thing. Backstage before we went out we would say “Here we go, we’re going our stuff, and somebody out there will appreciate it, even if we don’t know about it. We just have to go out and play.” We just tried to go out and have a good time playing music, like we’d done all our musical lives.Were you ‘upgrading’ your Simeon musical instrument during this time?

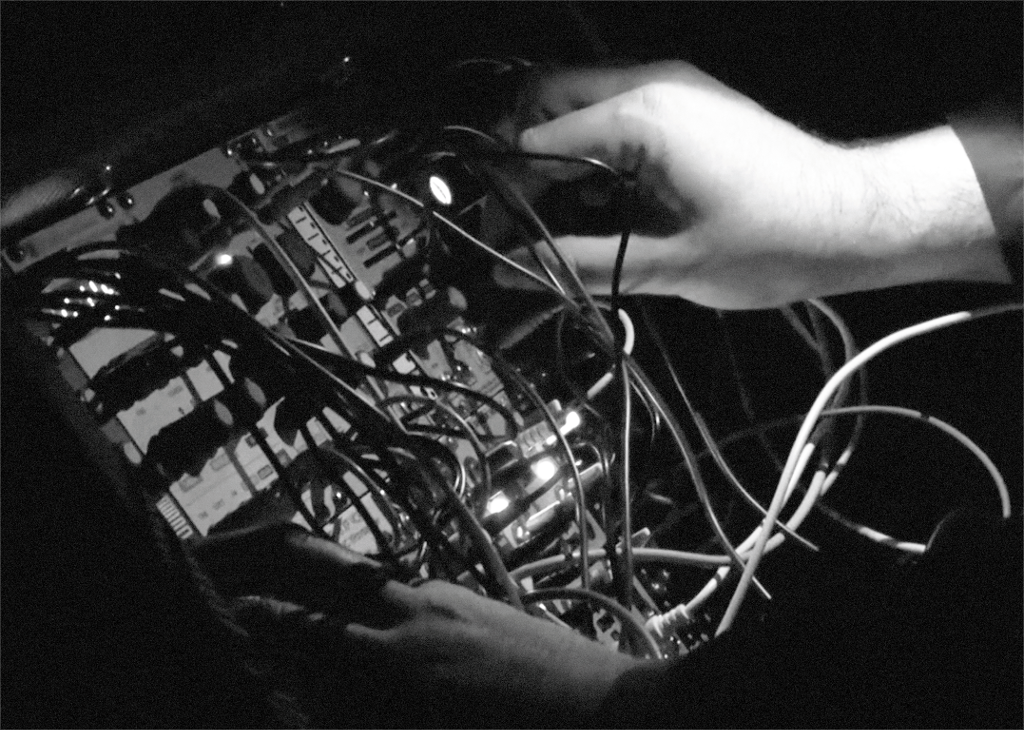

It was never the same thing from gig to gig. People would give me stuff, or I would find stuff, or discover something, and I would add it. Or something wouldn’t work and I would subtract it. It had a basic, modular format. I would carry it around in the plywood boxes that the various oscillators and the other electronic toys were mounted in. They would all sort of hook together with an old-time switchboard where you would plug in the jack into a maze of holes. So I kind of had it worked out that way. It was never the same.

It was never my idea to call it ‘The Simeon’, to name it after me. That was Kapp Records, it was a promotional thing they came up with. I would much rather not have been associated with it. It was this horrible, monstrous, untenable, unmanageable…thing! I mean, I could have just played a keyboard! [pullthis id="junk"]It was just pile of electronic junk. Stuff that we found in surplus shops in New York, mostly just in cardboard boxes sitting out on the sidewalk marked “Anything for $1”, that kind of thing.

Not knowing anything about electronics was probably a good thing. I didn’t know what I was buying. I would buy radio circuitry and telephone circuitry and anything that I could afford. I would take it home, put a positive lead on one side, and a negative lead on the other side, and see if it made a weird sound. I would see if it distorted the sound enough to make it interesting. And so I was able to come up with distortions that nobody else was into, simply because I didn’t know what I was doing. Many times the thing would just burn up, just go up in a cloud of smoke. Ha!

You played the recorder as well?

Yes, a recorder, a simple little wind instrument. I played it on “Seagreen Serenades.”

You were – are – often classed under the banner of ‘psychedelic’. Did you have any conception of that yourselves?

We were trying to play rock and roll. We didn’t know what psychedelic was. To this day I don’t know what psychedelic is. I guess it’s some kind of a mental attitude, I don’t know. Danny and I experimented with acid, but you wouldn’t have called us acid freaks. We didn’t ever play under the influence of even pot. We just found that when we went out on stage, if we had had a few glasses of wine, or a few tokes on a joint, we would think we were doing fine but if someone was taping us and we got to hear it later, we realised just how sloppy and how awful it sounded, even though we thought it sounded good. So we weren’t like many bands who would get completely ripped and go out and play with abandon.

Danny and I had to play a very clean and precise way or the music didn’t come off. It didn’t make it. So we always performed straight. We would get into party mode afterwards, but the music wasn’t drug-based in any way. I sort of think of psychedelic as people who play music on acid or make music to be heard while you’re on acid.That never occurred to us. I don’t know why we got the psychedelic label. I’ve never understood it. About 10 years ago a label in Chicago was putting together a compilation of psychedelic music, and wanted me to contribute something for it. I didn’t have a clue where to start. I didn’t know what psychedelic is, I mean, what is it? So I just wrote a children’s song, and they accepted it. They paid me. So I guess psychedelic is kind of child-like. I never have understood it.

What about Stanley Warren – how did he hook up with the band?

During the six month period when we were trying to figure out what to do, Barry got the bright idea of putting a notice up on the local bulletin board at Max’s Kansas City where all the artists and musicians in town were hanging out. It was the place, mainly because of the free chicken wings at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. I’m not kidding, that’s why the artists were all there. He put up a notice saying “Experimental rock band looking for lyrics. Poets invited to submit poetry.” We were swamped. We got 50 replies from various poets, who wanted their poetry made into lyrics and set to music.

One of them was Stan Warren. His stuff just lent itself to the rhythms that Danny and I were doing. I could easily sing “Oscillations, oscillations, electronic evocations” in a kind of loop-y way, it kind of fitted. He also included a line in his submission that said “I hope you like the poetry and, by the way, if you need to change anything to fit the music, you have my permission.” That indicated that he was willing to work with us. So we brought him around and let him listen, and he wrote a few poems after hearing us and let us use the stuff that he had written. So we kind of got into setting his poetry to music, along with others. There were several others, maybe five or six other poets. But Stanley Warren – this accountant-like guy from Queens, married with kid, he was anything but your idea of psychedelic, he didn’t look or act the part at all – but his poetry was very much workable. That, and the fact that he was willing to work with us, he didn’t have this huge ego attached to it, “You can’t change my poetry,” like some of them.

Anyway, so a lot of the songs on the first record, because we were so heavily involved in trying to develop a musical sound, we couldn’t really get into writing songs like we’d have liked to, so we used his stuff, along with Eileen Llewellyn, she wrote “Misty Mountain”. At any rate, by the time that we got around to writing the second record, we were more into “OK, here’s how we play our music,” so I started writing songs: “You and I,” “A Pox on You” and a few things. I became more involved in the musical creative process, and by the time of the third record I don’t think we were using any poets at all.

That was just an experiment on Barry’s part to bring in poets. He had no idea that there were so many poets out there. A truckload of poets.

Were you pleased with the two albums?

The first album I thought didn’t really reflect how Danny and I played live. I thought it was toned down quite a bit by the record label. They shortened some of the songs to make them more radio friendly. I don’t know, Danny and I had a more free-form, more expressive style when we played and we wanted to get that out there, but they wouldn’t let us. They just said that there was nothing commercial there, that maybe that could come later. I always felt empty. They wouldn’t even let us do one track. They let us extend “Dancing Gods” to about seven or eight minutes or so, that was as close as we got to how we played music live. Sometimes we would play for 15 minutes, and one song would blend into another without stopping. We’d go into an improvisational, electronic thing that was actually akin to what you’d hear at a noise concert now, a wall of sound barrage, and bleed that into another song. I kind of felt like that element of the band was missing, but c’est la vie. At least we had a record out. There were a lot of bands that didn’t have records. We didn’t complain.I still to this day have no complaints about Kapp. They did everything they thought was right. By putting us with the 1910 Fruitgum Company they weren’t trying to sabotage our career, they just had no idea what to do with us. So they were trying anything and everything to try and find an audience.

I’m much happier with Contact than I am with the first record. I think Contact gets closer to the rawness that we had. It’s a little more what you might say was getting punk-ish, which is kind of where we were. We weren’t hippies at all, we were kind of anti-hippie – we were New York street kids. We didn’t dress in hippie clothes, we never had flowers in our hair, none of that peace and love stuff.Is there any footage of the band at that time?

I don’t think so. I’ve seen stills, but I’ve never seen a video. Andy Warhol shot several things of us in our studio, but I don’t think he even had film in his camera. I think he just used that to open doors. He would go around with his camera and say “Do you mind if I shoot 30 minutes,” and people would let him and let him do whatever he wanted to do, but the stuff he was filming never saw the light of day. I don’t think he had film in the camera. He was kind of cheap. He wouldn’t spend money on anything, that was the reputation that he had. He wouldn’t even buy a drink.

Did you ever cross paths with the Velvet Underground at that time?

In a peripheral way. They used to come to Max’s Kansas City to hear us play, especially Moe Tucker. She thought Danny was just the most amazing thing she’d ever seen. She would come in and just sit in rapt attention, staring at Danny playing the drums. He almost got a little uncomfortable with her staring at him like that.

I remember seeing one Velvet Underground concert live. It was at one of those Exploding Plastic Inevitable things that Warhol did to promote the band. It was done in an armoury and there were about eight people in the audience. There was the band in the middle of the floor pretending to shoot up and singing “Heroin.” It just droned on forever. After about twenty minutes of the same song over and over again, we didn’t think that there was much going on and we left.

I do remember watching Lou Reed get down on his knees and pretend to tie off and look like he was shooting up on stage. We just sort of said, “Drugs? Why does it have to be associated with the music?” We never understood that, and never got into it.

What was the reaction to the second album, Contact, when that appeared?

It went over quite well, and advance sales were pretty good. A whole new tour was built on that, and then, all of a sudden, came the law suit because of the photograph on the back cover. Pan Am didn’t think it was funny at all and got an injunction against the sale and promotion of the material, including the music. So the album was taken off the shelves, and our tour was cancelled. It eventually lead to the demise of Kapp Records, and the break-up of the band.On the front cover there’s a Pam Am logo, above Danny’s head. They put it there in order to get some free publicity through what they thought was going to be a big record. They didn’t look at the back, or they never even thought about the consequences of us being superimposed on the wreckage of an airline crash. So they cleared it – their legal department cleared it, the advertising agency that did it cleared it, Kapp Records cleared it, Decca cleared it. Everybody OK’d it. It wouldn’t have gone into manufacture and distribution if it hadn’t had complete clearance.

It was just a month later, after it was already out there, some higher executive from Pan Am said “Wait a minute! Look at the back!” So they got their legal staff to get an injunction. They sued Kapp Records for an enormous amount of money, they sued us as a band, and us personally. It was $100,000, which in 1969 was like a million. It was more money than I had ever contemplated. It was just one of those things – all possibility of us growing after that point was gone.

The record never had a chance to do anything. I always thought that was a better record, which more explained what we were all about and was more like what we were like live than the first one.

What about the intended third album, The Garden?

It was before Kapp Records went under. They allowed us to go into the Record Plant in New York, and on spec they allowed us to cut the tracks for the third record. But then, during that period, that’s when Kapp went under. They couldn’t pay the bills. They couldn’t pay for the tracks and so we never were able to take them with us. The Record Plant kept them, and when the Record Plant itself went belly up, all of their assets were frozen, and auctioned, and all of our tapes were probably just bulk erased and went to some recording studio to be used as fresh tape.

It was before Kapp Records went under. They allowed us to go into the Record Plant in New York, and on spec they allowed us to cut the tracks for the third record. But then, during that period, that’s when Kapp went under. They couldn’t pay the bills. They couldn’t pay for the tracks and so we never were able to take them with us. The Record Plant kept them, and when the Record Plant itself went belly up, all of their assets were frozen, and auctioned, and all of our tapes were probably just bulk erased and went to some recording studio to be used as fresh tape.

What we found, twenty years later, in Danny’s attic, in a cardboard box, was the two-track dubs that had been given to him to take home and listen to in order to see if there was anything we wanted to change.

That’s what the original Whirly Bird release of The Garden was, it was off of those two-track tapes. We took them to a recording studio in Atlanta and had them cleaned up, the hiss taken out of them, that kind of stuff. Then we issued them, and then Bully Records reissued them, and now Enraptured Records has done it again.

After the law suit, how did the end of the band finally happen?

We just went our own ways. I got a job as a DJ in a nightclub. Danny got a job working behind the counter in a deli. We just kind of stopped playing live music. Our feelings were that we didn’t want to go back to playing regular music. If we couldn’t be Silver Apples, we didn’t want to play anything – once we had that little piece of candy, we didn’t want anything else. It was a very rewarding artistic experience, just going out and playing covers was not. Neither one of us really wanted to pursue a musical career if we couldn’t be Silver Apples, so we went our separate ways.

Was there no prospect of carry on as Silver Apples?

We were poison. We had a $100,000 lawsuit hanging over us. We had been partially responsible for the demise of a major record label. We were untouchables. Probably if we’d been The Rolling Stones someone would have said “Yeah, we’ll take a chance on you,” but we weren’t. We didn’t have a proven record of a million sales, you know? We were still growing, so that just never gelled. We couldn’t get anyone to give us the time of day.I reformed the band as a trio, and wrote all new material. We played one concert at The Village Gate, behind Larry Corryell. I introduced Silver Apples as a trio – bass player, drums and me. But it just wasn’t Danny. Danny came to the concert, sat there listening to it, cheered us on. He liked it, but I said to him, “Man, if I can’t play with you, it just ain’t Silver Apples.” I couldn’t do it anymore. That was around early 1970, and it was the last time I ever played as Silver Apples until the 1990s.

So what happened for you both after the band ceased?

I have no idea what Danny was doing. I bought a sailboat. I sold my amplifiers and bought a sailboat and sailed it down the Atlantic Coast, around Florida, up in the Gulf Coast. I was heading towards New Orleans, but I stopped in Mobile, Alabama, because my brother was there. I never left, I never carried on to New Orleans. I just thought Alabama was a great place. I’d never even really known that there was a coastal Alabama. I thought of it as being red mud and dirt and Birmingham firehoses and stuff like that. It had a bad reputation, but the southern part of Alabama is just an absolutely beautiful, unclaimed and uncharted little piece of real quality living. That’s where I am now, it’s where I’ve stayed.

Did you play any music during that time?

No, nothing. I worked in just about every odd job you can think of. I started with an ice cream truck, selling ice cream. I worked as a bartender, literally every job you can think of. I did some carpentry work, that’s always been my fall-back.Then I got a job as a film editor at a television station, and worked my way up. I started doing actual on-air reporting, as a news reporter. That was crazy, the bizarrest shit. I actually did that for about ten years because it paid well, for Channel Five in Mobile Alabama – “Simeon Coxe reporting live for Channel Five Action News.” It was the same as I did with the electronics; I just dove right into it and did it.

I eventually just moved to a different market, I moved to Virginia and was there for a couple of years, and then to Baltimore, Maryland, and was there for a couple of years. Then I got fired. And the reason I got fired was for telling the truth. So that’s why I got out of television, I said to myself “Man, if I’m going to get fired for telling the truth, what’s my future here?”

And you had no contact at all with Danny during this time?

No. None whatsoever.

During that whole period, were you keeping up with any music? Were you aware of what had happen in Germany and UK, with the rise of electronic music?

Not a thing. It was pointed out to me when I came back in the 1990s. People were saying, “Do you know what’s happened? Well listen to this!” and it was Kraftwerk, and it was Can, Suicide, bands all over the place that were picking up the ball and running with it after we had broken up. It was astounding. I was just floored. I had no idea, absolutely none, that it was going on.

What is truly amazing is that not only can you see the footprint of Silver Apples in those bands, but also in what happened in the 1990s as dance music and house music – “Velvet Cave” sounds almost like techno, in 1969.

Yeah, I’ve always loved “Velvet Cave.” I do it every set. It’s one of my favourite ones.

What was the story behind the 1994 TRC re-issue?

I’ve been asked many times what I think of that German bootleg, and I have absolutely no argument with them whatsoever, even though I’ve never received a dime for it, it was a complete rip-off. They didn’t even bother to try and clean it up; you can even hear the needle going across the record. They just dubbed off the record and issued it as a CD out of their basement or kitchen or some place. The quality is not all that great.

But even though I’ve never received a dime, I have no quarrel with it because, as in your case, it reignited the band, and got my career back on track as musician and not as a bar-tender and all the other stuff that I was doing. So even though several publishing agents have tried to track them down, I’ve never actively pursued them because I’ve always thought that they did me a tremendous favour really.

So what happened after the TRC bootleg came out?

Well, I started getting offers to come and play, to put the band together. The Knitting Factory just wouldn’t leave me alone. This one promoter said, “I’ll put you on with some of the bands around who were influenced by you. There will be a great support group. You will be honourably treated. Just put together something, I don’t care if you just come out and play a tambourine. Come out and be Silver Apples and let us see who you are, and if you can play an oscillator, bring it.” I thought, well, if I’m going to do this, I’d better do it right.

So I was on the bill with Suicide and I accepted the gig. It was three months away, so I had three months to build the band. I contacted some musicians I knew from the art scene in New York and asked them to help me put it together. We rented a rehearsal space, found a drummer and brought him in. We played him Danny’s recordings, and he started to get into how Danny was playing. I found an oscillator here and an oscillator there, at flea markets or whatever, and started learning the lyrics over again.Little by little, with a keyboard behind me to fill in the holes, we eventually put on a show at The Knitting Factory. It was unbelievable, people were standing in sub-zero temperatures, with snow coming down, in a line that went around the block and down the street, just in order get into The Knitting Factory. Movies stars were there, Ric Ocasek was there I remember, Johnny Depp, people just came out of the woodwork, and wanted to see what Silver Apples was all about.

I still wasn’t getting it. I still didn’t realise that the influence had gone that deep, and it took several performances like that, and several reviews by institutions such as The New York Times and New Yorker magazine to convince me that this was real, that this wasn’t something that was going to come back and burn me like Kapp Records before.

So I finally committed to it, re-launched Silver Apples and went on a quest for Danny. I started touring, I took it seriously again, and I haven’t stopped since.

So how did you find Danny again?

He was in upstate New York, in a little town called Kingston. He was working for the telephone company. He had no idea that it was going on, any more than I did. Because I had been out promoting, I had been going to radio stations and doing interviews, and every time I did an interview, I always said “And by the way, if anyone out there in the audience knows where Danny Taylor is, please contact this radio station.” I did that at every radio station I ever went to.

One day, a DJ at a little station in New Jersey was playing a Silver Apples song at a time when Danny happened to be taking a break and eating a baloney sandwich in his truck with the radio on. He heard himself. He couldn’t believe it. So he called the radio station and said, “I just wanted to thank you for playing my music. I had no idea anyone ever knew who we were.” And the DJ said, “Surely you’re not THE Danny Taylor, missing in action since the end of Silver Apples?” He said, “Yeah,” and the DJ said “My God! Simeon has been trying to find you for two years!” Danny just said, “Well, I’ve been right here. I haven’t been hiding.”That’s how it happened. This DJ called me in my house in Maryland, which is about 400 miles away, and told me that they had found Danny. He gave me the address. I just dropped what I was doing and drove all night. I was there the next day. We hooked up and practised, and played some gigs together. But then he got sick.

It’s the one part of the story that is a real tragedy.

Yeah, he was 55 I believe when he had the heart attack. I do continue to play his samples. I didn’t go out and get another drummer. I decided that we had been electronic since day one, so heck, let’s continue with it. I just sampled every sound I could find from him. Whenever I put together a drum beat behind a song now, it’s all from Danny. I think he would think that was just a hoot. I think he would love that I was doing it that way instead of another drummer trying to learn what he was doing. For one thing it wouldn’t be fair to the drummer. A new drummer would always be compared to Danny, and it would be totally unfair to any young kid coming in there and trying to be Danny.So it was either drop it, or continue on with this idea, sampling Danny and having Danny there electronically. I mulled it over in my head, and wondered whether an audience might think it was weird, or would they go along with it. The first couple of times I did it, they just loved it, so that was all I needed to hear.

Danny was an absolutely brilliant drummer. He was the reason that people would stay and listen to us, I believe, and take the time to try and figure us out – at least they could hear some good drumming, which they understood. It would take them a while to figure out what the Hell I was doing, but Danny would keep them glued to the band until they did figure it out. And once that happened, they would realise, “Hey, look what’s happening here. We’ve got music, but no guitars! That’s astonishing,” and then they would be into it. I think there’s no question that Danny was the glue. I was the thing that, I don’t know, floated around and was unpredictable. Danny was the solid rock, the glue, that held the band together.

The period in 1990s when you re-emerged and found a whole world waiting for you must have been really thrilling?

I was always pinching myself, saying “Like everything else in the pop music thing, this is bubble is going to pop.” But it never has. It’s been years now, and, if anything, it’s getting more solid as time goes on. Bands like Portishead and Spiritualized were at my last London concert. They just sort of are fans. They keep coming around. New bands keep coming and they offer their services. Jeff Barrow told me this last time around that anytime I wanted to come and record in his studio, just to come on down! It just keeps getting stronger and stronger. Maybe Silver Apples is not just a flash in the pan after all, maybe Silver Apples is more a slowly building cloud of smoke or something. It keeps getting under your skin, I don’t know. I’ve got some new material, so we’ll see if I can’t make something of that.What do you still feel you need to achieve?

Oh, new material I think. I enjoy playing the older songs, but I am really challenged and interested in playing the new material. And I’ve had an offer from a small record label to do another full length album. I’ve got enough material if I can just get myself organised and put it all together and clean it up. I think I’ve got enough material to do something like that. I think that’s what I’ll do this winter. I’ll put together enough material to get the thought processes going about releasing a new, fourth record. That’s where I’m at now.

What kind of technology will you be using?

To record I use Acid Pro on one computer, and Ableton on another. On Macs. I bounce samples back and forth between the two. I still use my old oscillators, but I sample them, and then assemble the recordings that way. I still try and stay true to the funky, old tube oscillator sounds, valve sounds. I’m sitting here looking at one now. I’m not using any keyboards still. Sometimes I’ll use a keyboard to test out a melody on and to try and sing along to, like in harmony. I’ll use a keyboard to try and work out where I should go with it, but that’s as far as I will get. I mean, I will never attempt to play one live or anything like that, or on record. I’m still just not Mr Nimble-Fingers. I can twist a dial back and forth like nobody’s business, but I can’t play the keyboard.Is that a physical result of the injury resulting from the accident in the late 1990s [when Simeon was seriously injured following a crash of the tour bus]?

Yeah, I’m not as nimble as I was. Every now and then I’ll drop a cup of coffee, because I just can’t feel it right. It just doesn’t have the same presence as it used to. But basically I’m cured. I’m very lucky to be walking around, so I’ll take what I’ve got, I don’t care. As long as I can still play, I’m fine.

Does Silver Apples allow you the financial freedom to be a full-time musician now?

Pretty much, yeah. I have the occasional odd job here and there that I still do, but basically I tour twice a year, once in Europe and one in the United States, and based on the income of those two tours, plus whatever small record royalties I still get, that works. I live very modestly, very simply – a little shack here in Alabama…

So we can expect to see you back in Europe before too long?

They’re already talking about building a tour around this new record I was talking about, so I’ve kind of got to get moving on that and get the record done. Then they will work the tour around it. I’ve got a tour coming up in the spring [2013] in the States, and so I imagine a tour in Europe will be in the summer, or even fall. I would like it to be festival-oriented, so maybe it will be summer. I love to do those outdoor festivals.

Do you have a working title for the new album?

Absolutely no idea. The single that I did this tour around last time was called “The Edge of Wonder.” I don’t know, but maybe “The Edge of Wonder” would be on that record. I imagine it would be, and we may end up calling it that. I really haven’t given it any thought yet.

Absolutely no idea. The single that I did this tour around last time was called “The Edge of Wonder.” I don’t know, but maybe “The Edge of Wonder” would be on that record. I imagine it would be, and we may end up calling it that. I really haven’t given it any thought yet.

Well, it would be an apposite title, given the story of the band.

I guess so. It’s just what happened.

Looking way back, what came to Silver Apples from your youth in the South?

Well, I was born in Tennessee, but when I was quite young my father moved the family to New Orleans because that was where he could find work. So I grew up in New Orleans.

I never really got into that funeral jazz thing that is sort of recognised as the ‘Sound of New Orleans’, for tourists anyway. My experience musically in New Orleans was the sort of music that they used to call ‘Race Music’, later it became R&B. It was the black scene. I thought that was where the real music of New Orleans was taking place, not in those fancy clubs for tourists on Bourbon Street. It was several blocks away on Rampart Street, where streetlights didn’t even work, where there were holes in the street, where black people went to hear people like Big Mama Thornton, Joe Turner, Fats Domino, that stuff.I would go. I would tell my Mom and Dad that I was going to a basketball game or a dance, and I would catch the streetcar down to Rampart Street and go into these clubs. I would often be the only white kid in the whole joint, and I was 15 years old. But nobody cared. Everybody was there for the music, and to have fun and to dance. So I would just stand at the back and watch Fats Domino dazzle those keys with his stubby little fingers. He would play these simple melodies and people would just go nuts! I thought that if I ever became a musician, I wanted to play like that!

I guess that’s where the seeds germinated, in those teen and pre-teen years in New Orleans, being exposed to Big Mama Thornton sing “You ain’t nothing but a hound dog, come around my door.” Then I heard Elvis Presley ruin it, and I knew the difference right then and there between commercial pop –and the poisons of it – and the real deal. I’ve always tried to stay close to the real deal.

*

Lying on the grass, with the sun warming my face, the long-sought music of Silver Apples came flooding into my senses. And, like an amazed palaeontologist stumbling across a species previously unknown in the fossil record, what I heard that summer’s day in Highgate completely re-wrote the accepted chronology.

This was electronic music, techno music, dance music, but in 1968 – not in the style of Joseph Byrd’s United States of America, however lovely that was – but in a way that still sounded modern, an electronic mirror image of the influence that The Stooges exerted over generations of guitar bands that followed in the decades after their demise. To a reasonably educated musical ear, Silver Apples’ constructions, patterns and tonalities could be heard echoed down the years in dozens of subsequent genres from Krautrock to techno.

Despite the summer heat, “A Pox on You” made the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end and sent a cold shiver down my spine. To this day, it still does.

“The Edge of Wonder” and The Garden are out now on Enraptured Records. More information at www.silverapples.com

-David Solomons-