The Klinker

The Sussex, London

20 September 2001

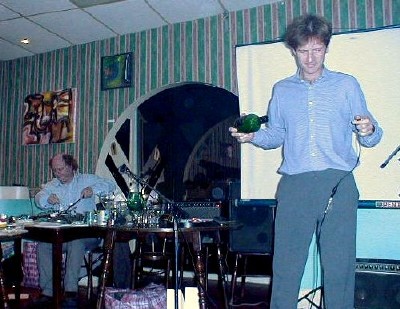

Well, The Klinker was its normal inchoate self: the irrepressible Hugh Metcalfe yelling “We start in ten minutes” as a half dozen apparently unrelated machine operators tinker with toy tape recorders, laptops, bits of wiring, large wineglasses, violin bows and Super 8 projectors. I concieve a momentary connexion between autism and the avant-garde – the unconnectedness, the lack of affect, it’s all here tonight at The Klinker.

But behind this buzz of overgrown childsplay there stand devices rarely seen at this venue: a full drum kit (without ethnicky extensions or innovative modifications), big Roland guitar amps, a Strat copy and a Westone bass. Tonight Tony Hill plays at The Klinker – former guitarist and mastermind of classic doomy Acid-Folk-Rock act High Tide. Largely unknown outside psychedelic anorak-dom, High Tide have a small but loyal following amongst those-who-know. The Klinker’s curator-general Hugh Metcalfe is one of those-who-know: It is difficult to imagine him as a young freejazznik in the Sixties as ready to rock out to High Tide’s tortuous, complex melodies as to stroke his chin to the discordant parp of Evan Parker et al. The Klinker regulars eye Hugh’s indulgence with amused tolerance – guitars are usually played with teaspoons here and the heavy grinning gap-toothed bassist is somewhat at odds with the faded middle class Bohman brothers, all neuroses and intellectual tics.

But behind this buzz of overgrown childsplay there stand devices rarely seen at this venue: a full drum kit (without ethnicky extensions or innovative modifications), big Roland guitar amps, a Strat copy and a Westone bass. Tonight Tony Hill plays at The Klinker – former guitarist and mastermind of classic doomy Acid-Folk-Rock act High Tide. Largely unknown outside psychedelic anorak-dom, High Tide have a small but loyal following amongst those-who-know. The Klinker’s curator-general Hugh Metcalfe is one of those-who-know: It is difficult to imagine him as a young freejazznik in the Sixties as ready to rock out to High Tide’s tortuous, complex melodies as to stroke his chin to the discordant parp of Evan Parker et al. The Klinker regulars eye Hugh’s indulgence with amused tolerance – guitars are usually played with teaspoons here and the heavy grinning gap-toothed bassist is somewhat at odds with the faded middle class Bohman brothers, all neuroses and intellectual tics.

And somehow, incredibly, The Klinker starts up. First up are Blind Plastic, a quartet of international twentysomethings who make buzz and glitch noises from their primary coloured toys and microprocessors as a bespectacled Japanese kid enacts a long and difficult relationship with a pink inflatable alien. The rock’n’roll band retire to the bar but the native Klinkerites follow every twist and turn of the ensuing pathetic drama. The pay-off is a fight between the players who throw firecrakers at each other’s feet – the lanky geek behind the laptop hides behind his coat and they somehow win our approval.

After a short interval the Bohman brothers emerge. Tall Bohman looks like an English professor while squat Bohman is a balding eccentric uncle. Their opener – a creaking squeaky door odyssey goes down well enough and the twin poetry anti-recitation that follows it is funnier than you might think. It is then that the boys launch into their landscape of tuned wineglasses – “nothing quite like a wineglass” squat Bohman observes. There is something genuinely touching and otherworldly about the sound they tease from what looks for all the world like the leftovers after a heady debauch. Tall Bohman stoops and jitters and puts on his dark glasses several times to inspect two objects that I cannot identify – we stray far into the territory of the obsessive compulsive.

After a short interval the Bohman brothers emerge. Tall Bohman looks like an English professor while squat Bohman is a balding eccentric uncle. Their opener – a creaking squeaky door odyssey goes down well enough and the twin poetry anti-recitation that follows it is funnier than you might think. It is then that the boys launch into their landscape of tuned wineglasses – “nothing quite like a wineglass” squat Bohman observes. There is something genuinely touching and otherworldly about the sound they tease from what looks for all the world like the leftovers after a heady debauch. Tall Bohman stoops and jitters and puts on his dark glasses several times to inspect two objects that I cannot identify – we stray far into the territory of the obsessive compulsive.

Their final number, an interpretation of a text written by a schizophrenic travelling by greyhound along the East Coast of America, is clever and at times feels close to revelatory. The brothers simltaneously read alongside a tape of other voices, sounds and psychic disturbances. It goes on a little too long but I cannot begrudge them the applause they earn at the end of the set.

Their final number, an interpretation of a text written by a schizophrenic travelling by greyhound along the East Coast of America, is clever and at times feels close to revelatory. The brothers simltaneously read alongside a tape of other voices, sounds and psychic disturbances. It goes on a little too long but I cannot begrudge them the applause they earn at the end of the set.

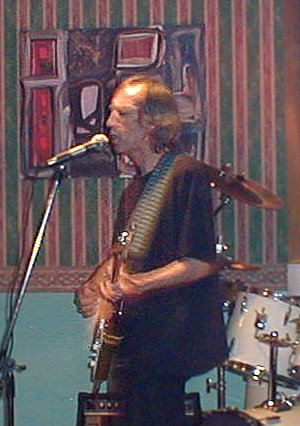

After a short film of mudflats and sea air from Hugh Metcalfe’s collection the rock’n’roll band arrive. Tony Hill has lost none of his touch in the three decades since the Sea Shanties album of yore – it’s a complex Bluesy fuzzwah sort of sound, abily backed up by Dean Holt‘s fluent bass playing and Sid Farrell‘s powerful drumming. They’ve become something of a four-to-the-floor power trio without the original High Tide string section of Simon House and Pete Pavli and I find myself comparing them to early Sabbath: perhaps it’s the trademark doominess of Tony Hill’s vision that drove him into decades of drug-fuelled depression. Hill is a weathered stick of a man, grey haired now, clad in the simple black jeans and t-shirt of a working guitarist. Sometimes you feel that he’s squeezing just too many notes into each bar but that’s what you listen to Tony Hill for. The Klinker proprietor is elated and most of the audience leave. High Tide’s early Seventies Puddletown period with the remains of Arthur Brown‘s Kingdom Come led them into free improvisation and Bartok, but this current incarnation only hints at their avant-garde roots.

A disappointing show? Well, no. it’s good to see Hill playing again even without High Tide – it’s an unmistakable sound even if incongruous in this setting and something I never thought I’d see live.

-Iotar-