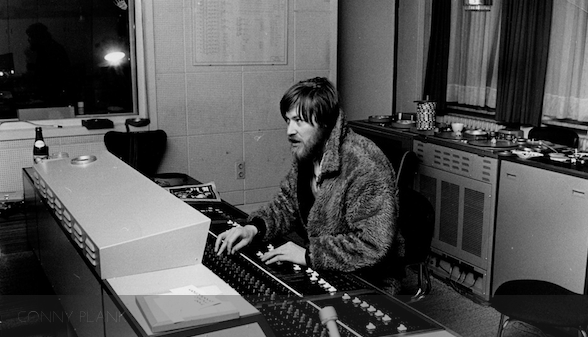

Grönland released their epic four-disc tribute to legendary producer Conny Plank in February 2013. Leon Muraglia of the Kosmische Club looks back at the man, his music and some of the artists whose distinctive, revolutionary sounds he helped create.

Grönland released their epic four-disc tribute to legendary producer Conny Plank in February 2013. Leon Muraglia of the Kosmische Club looks back at the man, his music and some of the artists whose distinctive, revolutionary sounds he helped create.

“Do you feel like a ride into the forest?”’ Conny Plank asked Brian Eno one warm autumn evening. After a short drive in Plank’s old Merc, they parked in a forest clearing and sat talking, surrounded only by the birds and the breeze. “Do you want to hear something on the radio?” Conny asked. “Why not?” Eno replied. He switched on the radio – and it broadcast the piece they’d been working on all day. Conny had set up a transmitter at the studio so that they could hear the day’s work in his car.

History

Konrad Plank, as producer and musician, inventor and pioneer, had a massive influence on modern production techniques and all electronic music that was to follow. Influenced by Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry as much as Karlheinz Stockhausen and Mauricio Kagel (both of whom he worked with as assistant), in the summer of 1974 Plank opened his own recording studio in Wolperath, 35 kilometres south of Cologne. There, in the 1970s, he built his legendary studio. Germany has had more than its fair share of legendary studios: Inner Space, Kling Klang, Hansa – but Plank’s was “the most important meeting point for groups and artists who were somehow new and “important,” according to Holger Czukay of Can (also a big fan of Stockhausen and Perry).His vision was that shared by many in 1970s Germany: to create a new future through uncompromising exploration, through inventing NEW music that was of it’s own time and place. Capably supported by his partner and “spirit at his side” Christa Fast, he worked in a wide range of genres including progressive rock, avant-garde electronics and krautrock. Cluster, La Düsseldorf, Kraftwerk, Eurythmics, Les Vampyrettes (a duo of Plank and Czukay), DAF, Brian Eno, Holger Czukay and Can all worked there. You can hear Plank’s influence most clearly on Bowie‘s ‘Berlin Trilogy’ (Low, Heroes, Lodger) and in early Public Image Limited.

Plank’s innovative techniques found favour with an ever-increasing number of artists during the ’80s. including Devo, Ultravox, Freur, The Tourists, Eurythmics, Ideal, Phew, Hunters+Collectors, Scorpions, Clannad, Killing Joke, Play Dead and Gianna Nannini. His ’80s work with – amongst others – Dieter Moebius from Cluster – is widely recognised as the first forays into what became techno.

Brian Eno remembers Plank being “healthily opinionated.” “Craziness is something holy,” he once declared. Plank wanted “to be surprised, to hear something new.” Tall and physically powerful, his imposing frame and strong opinions belied a “friendly and warmhearted” person, says Hans-Joachim Roedelius of Cluster. “He believed strongly in what we did and he supported us a lot.” He was a patron to Cluster, putting them up in his house in Hamburg. Moebius and Roedelius saw him as an occasional third member of the group, also touring with them.Plank was also a very versatile musician: he played guitar and keyboards on three Guru Guru albums, Cluster’s self-titled debut album, guitar and percussion on two Roedelius solo albums, and contributing guitar, keyboards, and vocals to the short lived band Liliental. Plank was a master of blending startling electronic soundscapes with conventional sounds, and was one of the first European producers to explore the possibilities of studio-as-instrument. Plank worked on Kraftwerk’s early material; he was also the man who added the delay to the synth bassline of “Autobahn” whilst Kraftwerk were absent from the studio. Imagine it without that delay.

Technicalities

Plank invented a system to photograph the mixing console from above with a specially developed camera lens which also doubled as a projector, through which he could project previously-taken photos onto the same desk and match up the settings from previous sessions. He also routed channels on the same mixing desk in order to “pan an instrument left and right, as well as dry and wet (reverbed), with only one fingertip, thus making a guitar solo fly through time and space.” (Guru Guru’s producer Petrus Wippel)

Plank would record loops of different notes onto multitrack tape so that each fader on the desk would control a different note, essentially turning the desk into an early kind of Mellotron. Plank’s drum sound was a very open, natural sound as opposed to the close-mic’ed, heavily compressed drum sound that dominated rock recording in the ’70s. Check the début NEU! album, which has the best drum sound ever. Michael Rother cannot overstate Plank’s influence on NEU!, often calling him the third member. “You end up with the backwards and forwards flying guitars that you hear in “Hallogallo.” That was a stroke of genius from Conny,” he says. “Without Conny we wouldn’t have managed a lot of things, and not just the NEU! albums.”Although he was sometimes financially forced to work with bands he was not into musically, “he liked to work with people he liked,” says Moebius. “And so he worked with many different people and in many different styles.” Plank was also due to produce produce the U2 album The Joshua Tree, but turned down the job (“I cannot work with this singer,” he said).

An immense workload combined with heavy smoking – entering his studio was often to walk into a wall of smoke (of all kinds) – eventually took its toll on his lungs and Conny Plank left the planet in 1987. Twenty-five years after his death, his records haven’t dated – and even though you can hear the master at work, he never stuck to one signature sound but experimented all the time.

Who’s That Man?

And so to the boxed set released in tribute to Plank. Whilst this compilation covers a lot of ground – you couldn’t expect it to cover everything – there are some surprising omissions. No C/Kluster, Kraftwerk, Ultravox, Kraan…but it does actually introduce you to some of his work you might be LESS familiar with (Ibliss, Psychotic Tanks, Fritz Müller). The music on these CDs is quirky, sometimes sublime, sometimes epic, sometimes harsh, adventurous, always full of character and often with a sense of humour (Moebius and Plank’s “Conditionier,” Psychotic Tanks’ punky “Security Idiots” and Conny’s own “Weinachtssong,” for example). These recordings are a testament to the subtlety that can be achieved by the perfect symbiosis of man and machine.The remixes on CD 3 are largely pedestrian and in one case, truly abysmal. Notable exceptions are the gorgeous Jens-Uwe-Beyer remix – a great, driving reworking of “Broken Head” by Automat – and the streamlined modernisation of “Conditionierer” by Fujiya + Miyagi. The real surprise is CD4: Moebius recently found a cassette whilst staying at a friend’s house containing previously unreleased material from a concert in Mexico in 1986. The audio is as patchy as you would expect and imperfect, but listen hard and you can hear some machines working hard, speaking of the future. This was one of Plank’s last public appearances.

Legacy

After Plank’s death in 1987, Conny’s studio was used until his wife’s death in 2006, when it was knocked down to make way for flats and his collection of excellent and often custom-made equipment sold. Five 24-track mutitracks have recently come to light, with Plank’s name next to Stockhausen’s. Who knows what they might contain?

His legacy? A passion for creating something NEW!, through technology or pure invention that some still share. The ability to surprise Brian Eno. That and some of the finest records ever made. You have them all, right?

-Leon Muraglia-

Visit the new Conny Plank website, source for many of the quotes used here; except from Roedelius, which were given directly to Freq.

2 thoughts on “Conny Plank – Who’s That Man?”

Leon from Kosmische writes about Conny Plank’s place in musical history http://t.co/9my2cjXJjT

Good article .

His studio was knocked down and replaced by flats .Speechless .

They did something similar with EMS .left their equipment to rot in a cellar .