Ever since discovering electronic music while at university, Ian Boddy has immersed himself in the world of synthesis, becoming a renowned exponent of the form, particularly active in ambient electronica as well as specialising in sound library creations and sound design.

Ever since discovering electronic music while at university, Ian Boddy has immersed himself in the world of synthesis, becoming a renowned exponent of the form, particularly active in ambient electronica as well as specialising in sound library creations and sound design.

Working with collaborators including Robert Rich, Chris Carter, Markus Reuter, Erik Wøllo and Nigel Mullaney, as well as with Mark Shreeve as ARC, he has been busy both live and on record releases through his own DiN label over the last few decades. For the latter, he has curated four volumes to date of the Tone Science compilations, which showcase some of the brightest names in modular electronic music today.

Interviewed for Freq as part of our ongoing collaboration with Philippe Petit‘s ever-expanding Modulisme series of synthesis sessions, Ian explains the hows, whys and wherefores of his unstoppable electronic music adventure.

When did you first become aware of modular synthesis as a particular way of making music, whether as part of electronic music in general or more specifically as its own particular format, and what did you think of it at the time?

Well, from a listening point of view I first got in to the music of Tangerine Dream via Phaedra and Rubycon as well as Klaus Schulze with albums such as Timewind around 1975. These were revelatory experiences as I simply hadn’t heard music like this before. It barely sounded as if it was made by humans, so of course I investigated the sleeve notes to find out what it was all about.

From a playing point of view, during my first year at Newcastle University in 1978 studying biochemistry, I was creating screen prints in my spare time down at an open access arts workshop called Spectro. A friend of mine who also loved the music of these German Berlin School artists mentioned that there was a sound studio upstairs which had some of the gear these guys used. So up I went and through the studio door into another world to be confronted by a VCS3 and AKS, as well as several reel-to-reel tape recorders. Many folk forget that just because those EMS machines don’t use the usual patch cable way of creating a sound, but rather their unique (at the time) pin matrix board, they are still essentially modular synths.What was your first module or system?

This would have been the Roland System 100-M. I got my first five-unit rack in 1982 as well as the four-voice polyphonic 184 keyboard. I still have both of these in use in my studio to this day, and over the years I have collected another 2 x 5 191-J racks of this excellent system.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

The Roland 100-M is a really easy system to use. Classic subtractive synthesis with a really nice ergonomic design. Most of the modules have inputs / outputs at the top and modulation inputs at the bottom, leaving the centre of the modules relatively unencumbered. To be honest, I’d already learnt basic synthesis on the VCS3, so the 100-M was far easier to use and certainly was more more stable tuning-wise. I used it all over my first vinyl release, The Climb, which came out in 1983.

Do you prefer single-maker systems (for example, Buchla, Make Noise, Erica Synths, Roland, etc) or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs.

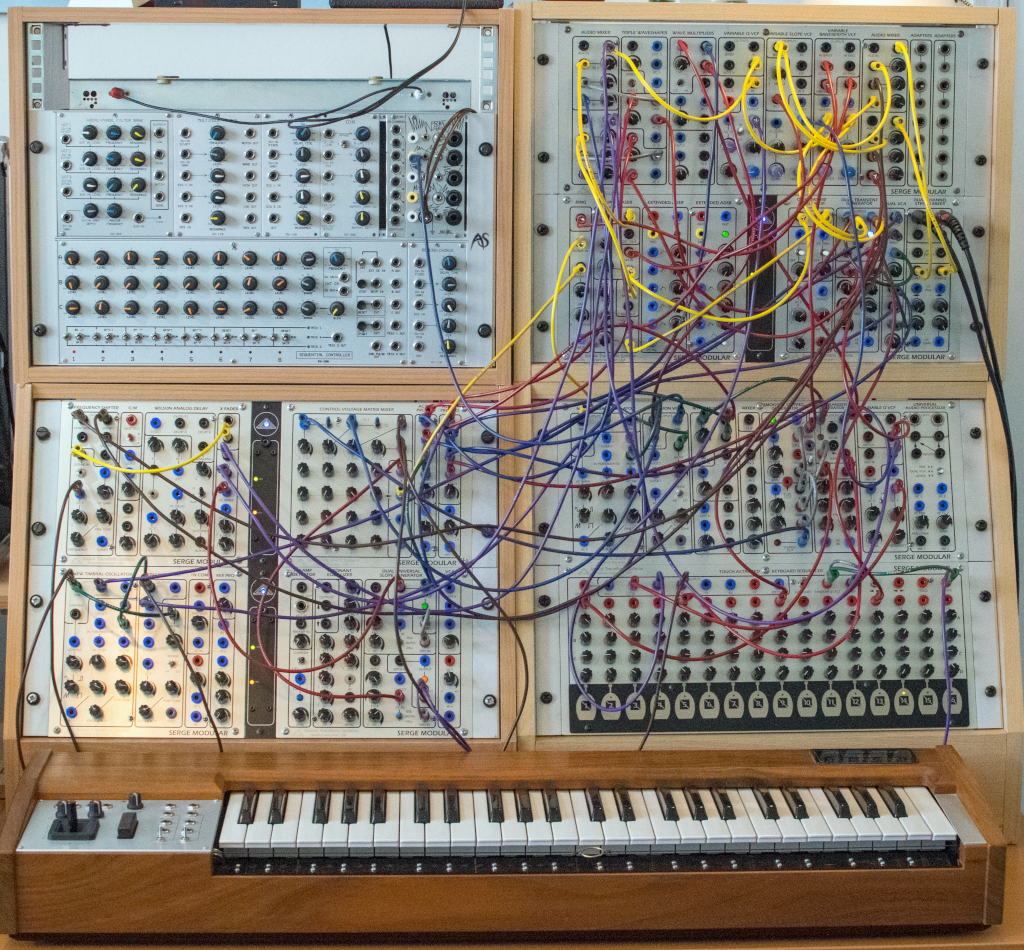

Both approaches have their advantages and disadvantages. As a musical instrument, I think I prefer the single maker system as it means the user interface is consistent and more predictable. So I have three such systems, with the Roland 100-M, VCS3 and my large 4U Serge system. The latter of these, the Serge, in particular is a beautiful instrument to patch and play. Having said that, there are some really interesting and unusual approaches to module design from the many artisan manufacturers we have today, and I have a large Eurorack system which I often treat as a sonic laboratory and quite often this works alongside my single maker systems.East Coast, West Coast or No-Coast (as Make Noise put it)? Or is it all irrelevant to how you approach synthesis?

It’s all irrelevant really. Ultimately it’s the music that matters and quite how you create the sounds that go up to make a particular composition are of secondary importance. And really apart from uber gear nerds, I don’t think most listeners really care — it’s the music that forms the emotional connection with them, not the gear.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

This all depends on what kind of work I’m doing. If it’s the more commercial library music world, I would tend to work more inside the box with a DAW (Ableton Live), with the modulars only being employed for some specific tasks. However, for my solo work, I often use the modulars as one large instrument, happily connecting between them all to get to where I sonically want to get to. Having said that, sometimes I limit myself to all-analogue sound sources, such as my original Tone Science album (DiN49), which was created with aleatoric self-playing patches, mainly on the Serge, but also with some Eurorack and 100-M. Here I would use solely analogue FX, such as the lovely pair of phasers in my 100-M, BBD delays such as the Wilson analogue delay in the Serge or spring reverbs via the Doepfer A-199.Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

Both — again, it depends on the music project. I often multi-track the modular gear and will usually record more than I think I will need of any particular patch and then later edit out the best sections. I’m very aware of the fact that each modular patch and performance is unique and can never really be repeated at a later date. But that’s OK, and in fact I think it helps you to be more creative and selective in what you do.

Also sometimes, such as my recent streaming performance for the Soundquest Festival, although it’s a live set, I recorded it to a multi-track HD recorder (using sixteen tracks), which gives me the option later of creating a much tidier, cleaner mix so that I can release this commercially. Although it’s nice to leave in some of the grit and dirt of a live performance, I don’t see the harm in trying to get the end mix sounding as best as you can, especially if it’s going to be released commercially.Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

I usually have it pre-patched with the option of a few tweaks that I can make with selected cable destinations. I’ll have some sequence lines and rhythms prepared ahead of time, but I often design some elements of randomness into these so that things are never quite the same twice. I’ll also do things like use scale quantisers that I’ll actually change live (like the Intellijel uScale) or CV sequencers from say the Malekko Varigate 8+, where I will manually change the sliders, knowing that the scale quantiser will keep it in key whilst I massage and adapt the actual range of notes played. This allows me a certain degree of solidity in the core of what I’m playing, whilst simultaneously making what is actually played a bit more random and varied.Which module could you not do without, or which module do you you use the most in every patch?

I really can’t answer this as that’s not the way I work.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

This depends on whether you’re just talking about hardware or software modular synthesis. These days, most of what can be achieved in hardware can also be mimicked in software in what potentially is a more convenient and cheaper form. However, that isn’t what hardware modular synthesis is about for me. It’s about the tactile approach where you are directly using your hands to control multiple parameters and modules simultaneously. This sense of immediacy, at least for me, is impossible to replicate in software. Not because it doesn’t sound good, but because you simply don’t have the same level of hands-on control that hardware allows.This leads to a whole paradigm shift in your thinking, whereby what you create on any particular day is a unique moment in time. Yes, I know software allows for 100% reproducibility and for some forms of commercial work that is essential, but from an artistic point of view I much prefer the unique sonic worlds that hardware modular synths can take you to.

Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

I’ve dabbled a bit over the years with Reaktor and it is truly capable of some astonishing sounds which I’d be happy to use and indeed have over the years. For me, it’s never a battle between what is best — software or hardware — they both have advantages and disadvantages. You as the composer, the artist, can choose which to use for your own personal reasons. If it works for you to help you express your musical ideas, then that’s all that counts.

What module or system you wish you had?

To be honest, I’m quite happy with what I have. If I had to pick one, it would be a Moog Modular, although I have worked with Mark Shreeve several times as the duo ARC and he has a large Moog system, so I’ve had access to one via that collaboration.

Have you ever built a DIY module, or would you consider doing so?

Nope, I’m terrible at anything to do with DIY. I really struggle to even use a soldering iron. I’m simply not interested. I’d rather just play these instruments and don’t care about the electronic components. I’m the same with cars — I have no idea how the engine works, I just want to drive it somewhere nice.Which modular artist has influenced you the most in your own music?

That’s a tricky one really, both from the point of view that I think you are influenced by everything you ever do in your life, but also because I wouldn’t say I have been particularly influenced by any artist who just uses modular synths. Right at the beginning of these questions I mentioned both Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze, who are certainly both electronic music artists, but who might not be considered modular synth musicians; but in many ways they have been more influential to me as a composer, probably because of the time when I discovered them, which was in my teens.

Can you hear the sound of individual modules when listening to music since you’ve been part of the modular world — how has it affected (or not) the way that you listen to music?

Well, musicians are probably the worst when it comes to listening to other artists’ work as they can be hyper-critical. And yes, certain instruments have their own sound, especially things like the VCS3, Buchla and Serge, to name but a few. But again, that’s not what is important to me — if the music speaks to me emotionally, then that is what I like. That makes you want to listen to that particular album again and again. Whilst modular systems are certainly cool, I think it’s important not to get hung up on the gear for gear’s sake — it’s the music that matters most.What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

I’ve already mentioned my performance at the SoundQuest Festival, which was very well received and certainly pushed what you can do with modulars for that style of music. This will be released on a CD later in the year. I’ve also just released Outland (DiN66) with my long-time musical collaborator Markus Reuter. The combination of his touch guitar and my modular work and French Connection Ondes Martenot-style playing has produced a beautiful album.

Then I am just about to release the fifth volume of the Tone Science series, with each volume featuring nine varied artists working with modular synths. Looking further ahead, I have created an album just using the VCS3 as the sound source, and with a little help from external CV such as a sequencer and envelopes I have multi-tracked the VCS3 to create a a record that I think will surprise many folk in quite what this venerable synth can do.Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

tI wanted to just use the Serge system for this, which is comprised of 6 x STS panels. Having said that, I did use my Echo Fix EF-X2 tape echo machine for some vintage feel on the output. For instance, the patch notes below describe the system used for the track “Diatribe”, which was based around the idea of having four VCOs all tuned to a diminished scale such as C, Eb, Gb and A. Each of these voices was then sent through a VCA which was randomly triggered by four looping AR envelopes from four unsynchronised DTGs.But there’s lots happening with the sound. There’s FM between each pair of VCOs, which I manually bring in and out. The pairs of VCOs are also cross faded and sent to two channels of the Triple Waveshaper that add extra harmonics via modulation. There’s also some ring mod in there, as well as the Frequency Shifter adding different tones and sounds. White noise is also coming through on the variable bandwidth VCF and phasers. So from a basic simple core idea with the tuning of the four VCOs, I am adding a lot of extra harmonic content and tons of modulation. One of the main things I’m controlling is the rate of modulation overall, as well as the shape of the AR envelopes, which is how the piece fluctuates from relatively calm, slow, organic swells to a couple of quite violent frenetic climaxes.

The tape echo, with its built in spring reverb, helps with the 1950s sci-fi B-movie soundtrack feel, which is what I was aiming for with this piece. And of course it’s a single improvised take that I’ll never be able to repeat.Who would your dream collaborator be for a Modulisme session or otherwise?

Well I’ve worked with many fine musicians over the years including Mark Shreeve, Robert Rich, Markus Reuter, Nigel Mullaney and Erik Wøllo, to name but a few. There are some other artists I am planning to work with in the future too, but I’ll keep those cards close to my chest for now. Every musician I’ve worked with so far brings something new and vibrant to the table, so I don’t go in for phrases such as “dream collaborator”. All these collaborations are very worthwhile exercises in creativity.

*