Richard Scott has been a key figure on both the UK improv and modular synthesis scene for many years, including the seminal Sines & Squares festival held at Manchester University. With a background in post-punk and the joys of improvised saxophony, Scott took to the modular synthesiser as his preferred instrument and also runs the Sound Anatomy label.

Richard Scott has been a key figure on both the UK improv and modular synthesis scene for many years, including the seminal Sines & Squares festival held at Manchester University. With a background in post-punk and the joys of improvised saxophony, Scott took to the modular synthesiser as his preferred instrument and also runs the Sound Anatomy label.

Interviewed by Freq as part of the ongoing cross-pollination with Philippe Petit‘s Modulisme sessions, Scott reveals he he was drawn into the world of modular synthesis and what can be learned by both practitioners and listeners from its particularities.

When did you first become aware of modular synthesis as a particular way of making music, whether as part of electronic music in general or more specifically as its own particular format, and what did you think of it at the time?

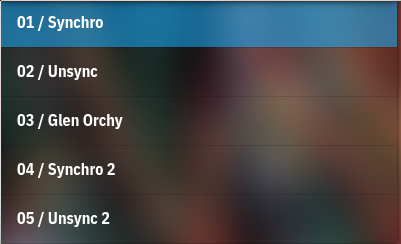

I had a Korg MS-20 when I was a teenager which had a patch bay, so the idea of patching was always there. I never had much interest in the keyboard aspect; generative patching seemed obviously truer to the idea of what a synthesiser was. But I never really understood the potential of patchable synthesis in any depth in those days. Much later I bought a Clavia Nord Micromodular and joined the Nord Modular mailing list — which at that time was an extraordinary resource full of much cleverer people than me. That is really when I started to learnWhat was your first module or system?

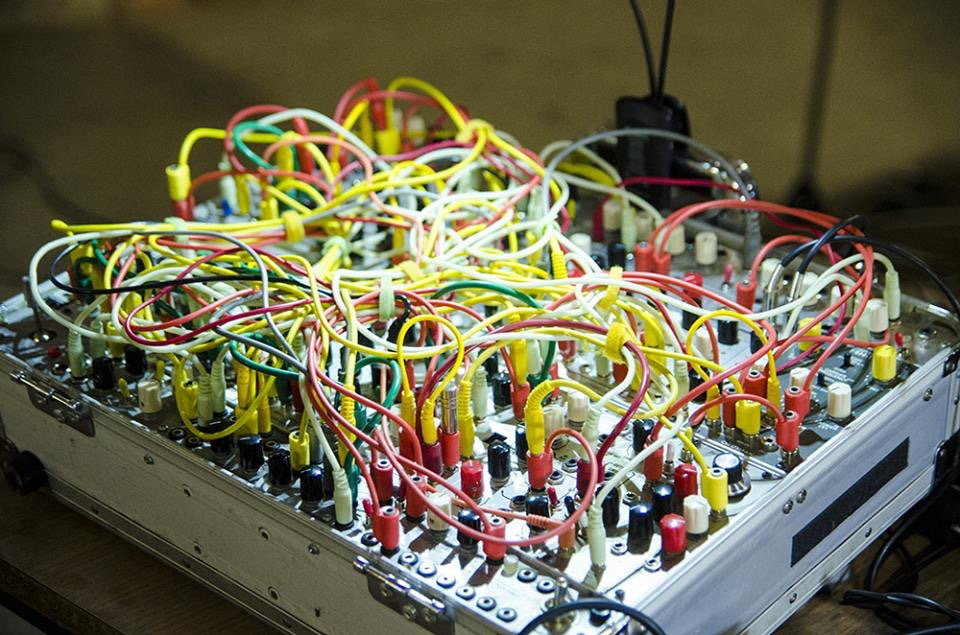

I then picked up a DIY Analogue Systems/Analogue Solutions setup with a dodgy power supply which was for sale ridiculously cheap – someone’s unfinished DIY project. It cost £300 and he was almost apologetic about selling it to me. This was a few years before the modular scene started reviving in the rather unexpected way that it has. So again I was reaching out in the dark mostly — I hadn’t played or even seen a true analogue modular synthesiser before and so I had no real idea what I had or what to do with it.

At the time I thought it was all a bit crappy and unstable, which turned out to be due the unsuitable DIY power supply, but also due to me not really knowing what I was trying to do. I eventually added a new power supply and got hold of all the Plan B modules and eventually Cwejman modules. I sold the Analogue Systems modules eventually and I still rather regret this.How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

It depends; patching didn’t take any time at all to learn. Patching in a way that facilitates live performance and improvisation is another thing. It took me five years before I felt confident to get onstage. Now its second nature. And I am still learning, of course.

Do you prefer single-maker systems (for example, Buchla, Make Noise, Erica Synths, Roland, etc.) or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs.

For the studio I like to work with single maker systems; Hordijk, EMS, Serge, Nord, Oberheim Xpander. Onstage I need what I need – and I need to be able to carry it — so it is nearly always a mixture of eurorack stuff. For a specific project, and if there is budget, I sometimes perform with the EMS or Hordijk – I can’t travel with so much stuff otherwise.Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

As modular as possible usually, though I often have a bunch of extra boxes and mixers, I am trying to give that up.Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

Both, all, whatever.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

100% pre-patched in performance. I have a version of a basic performance patch on all my instruments. It is hugely flexible, took years to figure out, and to be honest it hasn’t changed that much in the last seven years. I am not that interested in the predictability of the patching from zero “live-coding” approach that some people enjoy – although I do that in the studio all the time, there are parts of my brain I don’t want to be at all involved with performance. I’m all about speed and flow in performance; music moves more quickly that my brain thinking about patching does. So I need to catch up with it, not weigh myself down with modular administration.Which module could you not do without, or which module do you use the most in every patch?

Some kind of resonant filter, some kind of frequency shifter and some kind of delay. There are whole universes there.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

They teach me to listen and to work with sound itself; and that teaches me that my ideas about music are not that important. So I have to converse with this instrument, not simply dominate or be dominated by it. Many other instruments and tools don’t really encourage that kind of interactive relationship.Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

I studied Max/MSP but hardly ever use it. I like the Clavia Nord Micromodular, but rarely turn it on. I don’t seem to have any interested in screen-based programming at this point. It is just that I spent some years doing it, but I didn’t enjoy those years much. That technology doesn’t get me to the space of audio perception where I want to be: which is a plateaux of flux, flow and listening.

Which modular artist has influenced you the most in your own music?

Most of my musical influences come from elsewhere; Ornette Coleman, musique concrète, African music, Hindustani music, dub, early Cabaret Voltaire, etc. Joker Nies also reintroduced me to the idea of modular synthesis, years after the MS-20 days; he also introduced me to Rob Hordijk, which was an incredibly fortuitous meeting. I became one of the first to get a Blippoo Box from him, closely followed by a Benjolin and since then we have spent many hours together over the years. He is one of the greatest patchers and modular-thinkers alive, and of course, he is hugely skilled technically too. More than any composer, Rob’s design work was really the crucial link me personally.The thing is that I don’t think there are many masterpieces. The last few years are really the first moment when more than a handful of people really get to work with these tools in real time and so I think most of the musical history has yet to be written. The instrument is still young, most players are still finding their way and there is no set path to do that. You have to make you own path and what you want to get out of — it is all very personal, or it should be. It is all just a collection of electronic functions which can be as musically or unmusically useful as you like. The gear itself is just a container for these functions. Personally, I feel like I am responding very much to the functions as expressed within the context of the instruments themselves, rather than to the history or what other people did with them.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

Of course, Covid-19 has pretty much emptied my performance diary, although I didn’t get the chance to create a solo performance for the Moers Festival in June in the middle of the lockdown, which was quite an experience. I have a vinyl album release with Clive Bell and David Ross as Twinkle3 on the excellent Marionette label coming very soon. I would like to follow up my Several Circles double LP (Cusp Editions), but it is hard to find a label to commit to something like that these days, and I’d also like finish the second two Bastard Science albums on my own Sound Anatomy label.