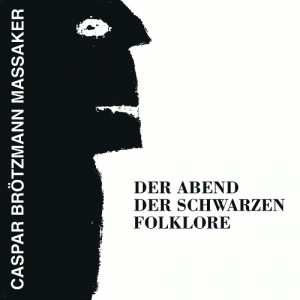

Next up in Southern Lord‘s Caspar Brötzmann Massaker re-issue series are albums three and four, and once again on album three, the line-up has changed a little. Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore was originally released in 1992, three years after Black Axis, and Frank Neumeier had made way for Danny Lommen on drums. The intervening years and the final track on Black Axis must have caused Caspar Brötzmann to review his ideas for the band, because Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore contains only four songs in forty minutes, and Koksofen contains only five in an hour.

Next up in Southern Lord‘s Caspar Brötzmann Massaker re-issue series are albums three and four, and once again on album three, the line-up has changed a little. Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore was originally released in 1992, three years after Black Axis, and Frank Neumeier had made way for Danny Lommen on drums. The intervening years and the final track on Black Axis must have caused Caspar Brötzmann to review his ideas for the band, because Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore contains only four songs in forty minutes, and Koksofen contains only five in an hour.

Interestingly though, Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore is not just about bludgeoning repetition. The album opens with a simple metronome cymbal sound, a gentle awakening combined with an early surge of guitar. The sound is desperate and obsessed as Caspar’s fingers run up and down the fretboard with no obvious thought in mind, but when his growled vocals arrive, all other noise shuts down apart from the tap of the cymbal and the sly squeal of the strings like angry dogs on leashes awaiting the opportunity to tackle whatever comes before them.

The vocals are whispered and threatening, and it feels like an attempt at torture. When the dreaded message is being revealed, so the guitar abuse stops — but as soon as the words are uttered, the howl of guitar continues with no obvious chords, just a relentless noise like that scene in North By Northwest where Cary Grant is being bombarded; except here, the planes are endless. At points, as in “Bass Totem”, the guitar sounds like a dragster ticking over, an exhaustless V8, wild and untameable. SunnO))) must have been listening to this, because the overloaded strings throb with a power and vibration that is disconcerting. A single strum reverberates through Hell and the resulting feedback is just tonal glee. After six years at the helm of the Massaker, for Caspar it was still about throttling sounds from the guitar, pushing it to see what it can do and revelling in the results. As well as playing bass, Eduardo Delgado Lopez is listed as playing ratchet here, and you can here the metallic creep grinding in the background. The vocals are guttural, like a drunk with a cut throat, and the solemnity and sincerity of delivery make Nick Cave sound lighthearted in comparison. The tension runs high when the guitar is silenced and Danny Lommen shuffles in a basic cymbal pass at the these queit moments; but it is all about the guitar and Caspar Brötzmann’s struggle to silence it, if only for a moment, before it tears itself free. I don’t even know if chords are being played here, but when a track reaches a point that might be considered a song structure, at least the rhythm section has something to do and takes the opportunity to gallop headlong into the distance.More whispering on “Sarah” is accompanied by the ghost of feedback, the struck strings resonating and bending wickedly, descending into the abyss, wailing like a tormented thing, a hideous police alarm while the bass shudders heavily in the background. It is interesting that these tracks would have been produced at a time that would have put them as contemporaries with Swans and Sonic Youth, but where the Massaker differs is the abject frustration and fury that seem to pour from the grooves. The album ends with the guitar not even sounding like a guitar, and you find that it has been quite a tense listen. You never quite know what form the songs will take and how long the creeping inertia of the quiet sections will last. It frays your nerves a little, so to sticking the fourth album on straight after might no be so good for your health.

*

Koksofen was released only a year later and essentially builds on the themes of Der Abend Der Schwarzen Folklore. A gentle intro, the scrape of the strings, the swirl as things progress and the shriek of feedback once it is unleashed. The guitar sounds even less patient and the brutality of an intense power trio is here from the outset.Danny Lommen is back on the drums and here he has a greater part to play, the evil metronome to Caspar’s diabolical vocals. The tracks are structured more to gain benefit from the rhythm section, and the bass is really tasty on fourteen-minute opener “Hymne” and the track revels in its obsessive repetition and malevolent acts of suppression. The creak of a ship at sea — or is it the creak of an ancient cradle? — dominates proceedings on “Wiege”: you are awaiting an explosion and once again the group is playing with your nerves, waiting, waiting until it crashes over you like freezing cold water, the high-pitched squeal, the angry voices, the dominance of the bass and drums.

The only trouble with all this is that it can become too much at times, the galloping fret-board madness, the grinding rhythm section battering you into submission; it is as if they don’t know how to stop once they start, and even the pretty (within reason) intro to “Kerkersong” descends eventually into helter-skelter craziness. After the Langston Hughes-injected “Schlaf”, I was becoming weary and I never thought I would tire of long bursts of single note feedback — so when the distant explosions and earth moving noises of “Koksofen” appeared, it caused me to sit up and for sixteen minutes, and this atmospheric, slightly hysterical, industrial landscape completely changed my notion of the band. Huge machines move slowly across a broken landscape. The ground creaks under the weight as the machines growl and groan, but without overwhelming the uneven rhythm, random blasts of bass strings and subterranean bellowing. It keeps us on edge, waiting for what comes next, but it differs so much from what came before that it is hugely welcome. The groans and creaks are relentless, and while there is space here, the atmosphere is toxic. Although “Koksofen” feels calmer somehow than the previous tracks, as everything draws to a close, you feel as though these will be the last sounds you will ever hear.These two albums push Caspar Brötzmann’s idea of the Massaker further into uncharted territory and as such are extraordinary documents of one man’s guitar vision; but it is the last track on Koksofen that could have opened another realm for them. Unfortunately, this was the last proper Massaker album before 1994’s reworkings on Home, and so they left behind a perfect legacy of primitive guitar abandon that has never been equalled.

-Mr Olivetti-