Even in this age of Tunng, Espers and countless assorted other groovy out-there New Folk outfits who are busy fusing ancient melodies and instrumentation with samples, beats and all the trappings of hip urban coolness as fast as their little hands can programme, for most people the word ‘Folk’ still brings to mind images of worthy acoustic sing-a-longs, beards and real ale as relentlessly as driving rain on a Bank Holiday dowsing trip to Wessex. Let’s face facts, ‘Folk’ still too often struggles to shed the ‘hey nonny nonny’ and ‘all around my hat’ fuckery of its rather tiresome mid 20th Century incarnation. Don’t get me wrong, I love ‘Folk’ music, and its quiet but considerable influence in ‘Rock’ is often cruelly overlooked in favour of the more gritty and credible – and sexier – ‘Blues’ (…go out and play Traffic’s awesome “John Barleycorn (Must Die)”…), but it’s just so damned…nice. Isn’t it?

Even in this age of Tunng, Espers and countless assorted other groovy out-there New Folk outfits who are busy fusing ancient melodies and instrumentation with samples, beats and all the trappings of hip urban coolness as fast as their little hands can programme, for most people the word ‘Folk’ still brings to mind images of worthy acoustic sing-a-longs, beards and real ale as relentlessly as driving rain on a Bank Holiday dowsing trip to Wessex. Let’s face facts, ‘Folk’ still too often struggles to shed the ‘hey nonny nonny’ and ‘all around my hat’ fuckery of its rather tiresome mid 20th Century incarnation. Don’t get me wrong, I love ‘Folk’ music, and its quiet but considerable influence in ‘Rock’ is often cruelly overlooked in favour of the more gritty and credible – and sexier – ‘Blues’ (…go out and play Traffic’s awesome “John Barleycorn (Must Die)”…), but it’s just so damned…nice. Isn’t it?

Roger Wootton, however, always had other ideas. Forming a band with several compadres in 1968, he took their name from a lesser-known 1634 work by John ‘Paradise Lost’ Milton – commonly known as Comus – in which the titular character is a malign, debauched necromancer intent on having his wicked way with the female protagonist, ‘the Lady’, and slaking his considerable libidinous appetite. For those paying attention at the time, the clue was really all in the name; that and the fact that their early rehearsals centred around acoustic jamming to Velvet Underground numbers.

Wootton and his fellow malfeasants, finding too much that was soft, cosy, cloying and false in the contemporary Hippy movement instead took the left-hand path, constructing a sound that was aggressive and confrontational, with lyrics that dwelt deep, deep in the woods, all brutal imagery of mental rage, abduction, violence, violation and murder. Wootton sublimated his difficult relationship with his mother into the band’s twisted approach, and though it doubtless made Sunday lunch a rather uncomfortable affair, it enabled him to enter fully into his jet black stage persona, their singular take on ‘Folk’ music making the band much more akin to the Punk movement of later years than to any of their Hippy peers. One key early champion was David Bowie, then beginning the early phase of his post-Space Odyssey ascent to the Rock firmament, who gave the band both an early residency his Beckenham Arts Lab and a support slot at his prestigious South Bank gig in November 1969. Legend has it that he was more than slightly aggrieved when Comus proceeded to blow him offstage. Ungrateful sprites.

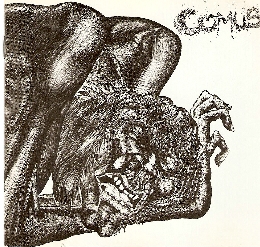

The band’s first album, First Utterance, duly appeared in 1971. The sleeve featured a stark, black biro drawing by Wootton, a hairy, twisted Comus, all jutting ribs and priapic leer; it looks more Rudimentary Peni than Pentangle. The music contained within the grooves was, for the simple Hippy folkie, no nicer than the cover, seven original compositions of woodland Paganism and violent physical communion. This was no ‘getting it together in the country,’ no peaceful rural backdrop for a sunshine dream of self sufficiency and dilettante agriculture. This was the dark, evil spirit of the forest coming to defile you, slit your throat and dump the body deep amongst the trees where it would never be found. Perhaps unsurprisingly, hostile critical reviews and general public revulsion soon terminated the band’s existence, with their last live performance taking place in 1972. Two years later the rump Comus did reunite, with assistance from members of Henry Cow and Gong, but the resulting album To Keep From Crying fared no better than its predecessor. And that, as they say, was the end of that. Except, of course, that it was not.

The band’s first album, First Utterance, duly appeared in 1971. The sleeve featured a stark, black biro drawing by Wootton, a hairy, twisted Comus, all jutting ribs and priapic leer; it looks more Rudimentary Peni than Pentangle. The music contained within the grooves was, for the simple Hippy folkie, no nicer than the cover, seven original compositions of woodland Paganism and violent physical communion. This was no ‘getting it together in the country,’ no peaceful rural backdrop for a sunshine dream of self sufficiency and dilettante agriculture. This was the dark, evil spirit of the forest coming to defile you, slit your throat and dump the body deep amongst the trees where it would never be found. Perhaps unsurprisingly, hostile critical reviews and general public revulsion soon terminated the band’s existence, with their last live performance taking place in 1972. Two years later the rump Comus did reunite, with assistance from members of Henry Cow and Gong, but the resulting album To Keep From Crying fared no better than its predecessor. And that, as they say, was the end of that. Except, of course, that it was not.

All through the shock and awe of the Punk years, the Eighties alternative and the Nineties million fractured sub-genres, Comus’ reputation grew steadily attracting audiences drawn by their unforgiving musical danse macabre. When Current 93 covered “Diana” on their 1990 Nurse With Wound/Sol Invictus split LP set, Comus’ status as neglected British experimental progenitors was complete.

In Sweden too, the legend of Comus had done nothing but prosper like a strangling vine over the intervening decades, spearheaded by the unflagging patronage of Mikael Akerfeldt, leader of progressive Death Metal outfit Opeth. Then in 2007, Akerfeldt’s friend and promoter Stefan Dimle decided to take proceedings one step further, and, with huge amounts of cajoling and pleading, persuaded the slumbering homunculus of Comus to awaken from its long sleep in order to perform at his Melloboat Festival. Finally, in March 2008, over thirty five years after their last performance, Comus once more appeared live, leading their deathly chant across the Melloboat, which took place over 40 hours onboard the Silja Symphony, a 204m luxury cruiser, and the largest ferry on the Baltic Sea. East of Sweden captures the band’s set, as uncompromising in 2008 as it had been almost forty years beforehand.

Kicking off with “Song to Comus” in which our eponymous anti-hero enjoys some unabashed maidenhead puncture in the forest (“Naked flesh, flowing hair, her terror screams they cut the air”), the band follow with “Diana,” another threatening tale of chastity meeting with lust under the woodland canopy and coming off a distinct second best. Featuring some wonderfully evocative violin from Colin Pearson, “Diana” is pure Wicker Man, a cheery sing-a-long for a pleasant evening spent the lounge bar of the Green Man as a virgin policeman blazes away merrily outside. At the track’s end however, instead of a stentorian “You’ll simply never understand the true nature of sacrifice…” the band instead greet and acknowledge the audience, “You are amazing. Thank you. What a welcome.” It is a brief moment, but genuine and truly heartfelt. Comus may have been curled up asleep in his verdant woody bower these last thirty six years, but now he’s back, and his followers have at last gathered to worship and give praise.

“The Herald” follows, a beautiful and gentle respite from the business of depravity, sung with ageless grace by Bobbie Wilson, her voice belying the years with its clarity and purity. Still, after that brief moment of quiet contemplation it’s time to return to the business of the day once more; primeval explosions of lust amongst the trees. “Drip Drip” is truly Comus’ most demented piece of work, nine minutes of pure musical psychosis in which Wootton gives vent to every last piece of primitive evil dwelling within him, “Your lovely body soon caked with mud, as I carry you to the grave, my arms your hearse.” When he repeats “I’ll be gentle” over and over in a voice that sounds like it has cloven hooves, it is, quite frankly, difficult to believe him. Drip, drip from your sagging lip indeed.

Leaving the forest temporarily, “The Prisoner” is a tale of electro-shock therapy conducted on a mental patient confined to an institution and praying for release from the living Hell being endured. Clearly, even when Comus leaves his woodland lair for the city, nothing endured is any sweeter. Returning to the band’s very early days, “Venus In Furs” takes the Velvets’ magnum opus and runs it through the dark folk filter, turning Lou Reed’s tales of urban NYC sado-masochism into a natural descendant of traditional British murder ballads such as “Pretty Polly.” Finishing off with an encore reprise of “Song To Comus,” the CD ends with the band basking in the adulation that had been denied to them decades before, “Bloody Hell have we enjoyed it.” And why not? There can be fewer sweeter victories to savour than having been far ahead of the curve, and the opportunity to come back much later and be vindicated for it.

Coming only a week after a Justice Secretary has faced raging volleys of approbation for his comments on the nature of rape and the sexual exercise of power, doesn’t the music presented on this CD tread a much more ethically dubious line? Indeed it does, and no band recording their first album today could expect to produce such material and find any level of mainstream musical acceptance. Yet it has always been the business of traditional folk music to delve into the darkest recesses of the human psyche and explore the horrors that lurk there. Like myth in its wider sense, such folk songs were the framework in which the darkest human perception and behaviour were explored, codified and handed down as both example and warning. The music of Comus forms a seamless part of that continuum, as if it had been written in 1671 rather than 1971, and sounds as troubling, evil and thrilling as at any time since.

Just stay out of the woods, OK?

-David Solomons-

2 thoughts on “Comus – East Of Sweden”

Hi David/Freq magazine,

Thanks so much for this amazing review! And so well written and referenced.

Whereabouts are you? We’d be pleased to give you a free ‘in’ to a show if you are in the UK?

B.

Thank you David. The best review of my friends Comus and one that really gets it!