London

21 September 2013

It is a mild, early autumn Saturday night and Upper Street is the very picture of modern urban revelry. Outside the doorways of fashionable bars and clubs, the pavements are clotted with thick knots of drinkers and smokers, the ‘dun-tsch, dun-tsch, dun-tsch’ beat of anonymous dance music bleeding out from their dimly-lit interiors into the warm evening air.

There is scarcely a free chair around the outside tables of the chi-chi restaurants, every surface groaning under cornucopia of plenty: pan seared scallops, herb roasted pork tenderloin and quinoa-crusted plaice, chilled Chablis and Blue Mountain double espresso. Everywhere stand men with casually unbuttoned striped shirts and hair thick with extra-hold gel, whilst women with glowing blonde hair and micro-skirts totter atop their high heels. An enormous shocking pink stretch Hummer glides past, one of its darkened rear windows lowered as a girl clutching a precarious flute of champagne yells “I’m getting fucking married!”, startling unwary passers-by whilst her friends cackle their encouragement from inside.A doorway. Just to step through it allows the entrant immediately to become a time traveller, hurtling backwards decades in time, centuries even, to an almost vanished world, one that to the majority of the modern metropolitans outside is now almost as remote as that of Watt Tyler leading the Peasants’ Revolt or the sight of the Roman Legio IX Hispana (Ninth Spanish Legion) encampment in Lincoln. Yet for one night only, those of us lucky enough to step inside can lift the lid and look into a strange and wonderful box of delights.

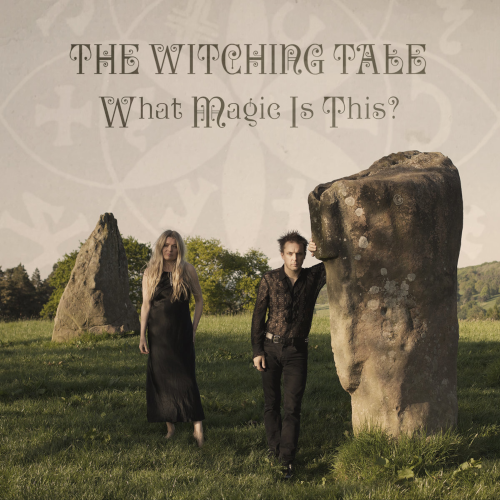

Drifting striations of dry ice hang across the interior space of The Assembly Rooms, everything suffused with a delicate red glow of illumination and a hushed atmosphere of expectancy. Taking the stage is the duo of Stephanie Hladowski and Chris Joynes, their unenviable task to open the proceedings before the later emergence of two veritable legends of British music. Given quite how desperate the majority of the audience is for even a glimpse of those that will follow, that this is no small (t)ask. Yet with the crystal clarity of Hladowski’s voice and the lovely ringing chimes of Joynes’ guitar, the audience are quickly and convincing won over.Performing eight “traditional English tunes,” there is nothing revelatory about the material or their presentation of it, yet the austere beauty of the songs, and the passionate devotion of the players more than breach any over-familiarity or cynicism. “Greensleeves,” a Morris tune by Gloucestershire fiddler Stephen Baldwin (said by him in 1950 to be “one of the oldest there is; my father said it was an old tune in his time”) is utterly exquisite, whilst “The Dark Eyed Sailor,” an old East Anglian tune, relates the sorry story of a young lady whose virtue is undone by the allure of a jolly Jack Tar. The highlight though is arguable “Bold William Taylor” (dating back several hundred years and covered by such luminaries as Martin Carthy and June Tabor), which tells the enormously fun tale of a young girl who, when her true love is taken away to go and fight in the navy, dresses up as a man and sets off to find him. A somewhat unfortunate wardrobe malfunction in the heat of battle rather exposes the fact that she’s not quite the sort of fellow that everyone took her to be yet, after having shot the titular Taylor for consorting with another woman, Bold William’s commanding officer (in an unprecedented act of gender equality some 150-odd years before the Sex Discrimination Act 1975), overlooks this and makes her his new field commander.

The only fly in the ointment for the duo – who are clearly and disarmingly cognisant of their place in this special event – is Joynes’ trouble tuning and retuning between songs. With the heat and the light and the audience’s stare of expectation, the sharpest ear can occasionally have trouble working from EADGBE to DADGAD and back again – even Davy Graham himself tripped up on this one from time to time. Joynes might take a tip from an audience member sitting attentively a few rows from the front: Thurston Moore always has a sufficient stock of tuned guitars on hand to keep exactly this kind of technical intrusion to a minimum. That is small beer really, though, for in such a high-pressure situation Hladowski and Joynes have delivered a joyous performance.

Whilst packing up his guitar Joynes calmly tells the audience “In 15 minutes it’ll be Shirley Collins, which is a sentence I never expected to hear myself say,” and it’s difficult to disagree with him. A sense of the audience’s excitement is palpable as they await the entrance of the woman that Billy Bragg once memorably referred to as “without doubt one of England’s greatest cultural treasures.”

And so, after a very brief turnaround, the grande dame of English folk music duly saunters onto the stage and takes her seat at stage left, whilst simultaneously the actor Pip Barnes sits across on the other side. Now scarcely two years shy of eighty, Collins, as well as the beauty and ferocious talent of her youth, can now add gravitas and dignity to her résumé. The sheer scope of her recorded discography, the tales of her incomparable vocal virtuosity, the vast treasure trove of English song that resides within her are almost tangible in the audience’s reverence for her. When she speaks, her voice is rich like port wine. Yet tonight, to the surprise of much of the audience, Collins will not be singing.Instead, accompanied by Barnes, she presents I’m a Romany Rai, an illustrated lecture about the Gypsy singers and songs of southern England. At first it’s hard to stifle the creeping tendrils of disappointment (like seeing Scott Walker sitting in the control room at his Drifting & Tilting event and having to pretend that you really don’t mind not seeing him sing the songs himself), but it quickly obvious that this is really something really very special and intimate, and that those in the room are privileged to have one of the most important British singers of the last 100 years guide us through a tour of a closed and secret world.

The lecture focuses on the songs collected by Peter Kennedy and Mikes Yates for the BBC in a period from the 1950s through to the 1970s. With Collins narrating and Barnes providing accompanying voices, we move from the old lavender street cries sung by Janet Penfold in Battersea to Louie Fuller’s tales of hard seasonal labour in “Hopping Down in Kent” to Jasper Smith singing “Hartlake Bridge,2 the tragic story of the death of 30 of the aforementioned hop pickers in 1853 when their horse tripped as it was crossing the side of the bridge, their wagon collided with the side, and the bridge collapsed into the river below, already swollen with floodwater and now a malignant whirlpool of strong currents.

The audience sit in rapt attention listening to the scratchy recordings, lost in time for several minutes and immersed in the hard, crazy, joyful life of the Romany, whilst gazing at the photographs of the singers that Collins projects. There are moments of hilarity, as when Cecil Sharp, folk collector supreme, is aware enough to realise the danger of being caught alone with the wife of an approaching Romany man (possibly under the influence of strong drink), and chooses to diffuse the situation by greeting him with the cheery words “Merry Christmas. Stop a minute! I’ve got your wife’s voice in a box!” There are also moments of amazement, as when Collins relates the story of Phoebe Hessel, who famously disguised herself as a man and joined the British Army in order to be with her lover Samuel Golding and was only discovered when she undressed in order to be whipped for a disciplinary infraction. Hessel lived to be 108, and still has both streets in East London and a Brighton bus named after her.The contrast between what we seeing and hearing in here, the lives of hardship, forbearance, longing and hope, and the relentless – and thoughtless – leisure consumption happening only feet from the door of the venue are hard to miss and this, perhaps, is no small part of what Collins is trying to ask the audience to consider. There are lessons to be taught to us by these sepia ghosts of our collective past, if only we are smart enough to listen to them.

Though there remained a twinge of sadness at not hearing Shirley Collins herself sing, I felt profoundly grateful to have witnessed this. And the sight of Thurston Moore, alternative guitar hero of American noise music, listening attentively as six year old Sheila Smith sings the little ditty “Sweet William” is surely one to be treasured forever.

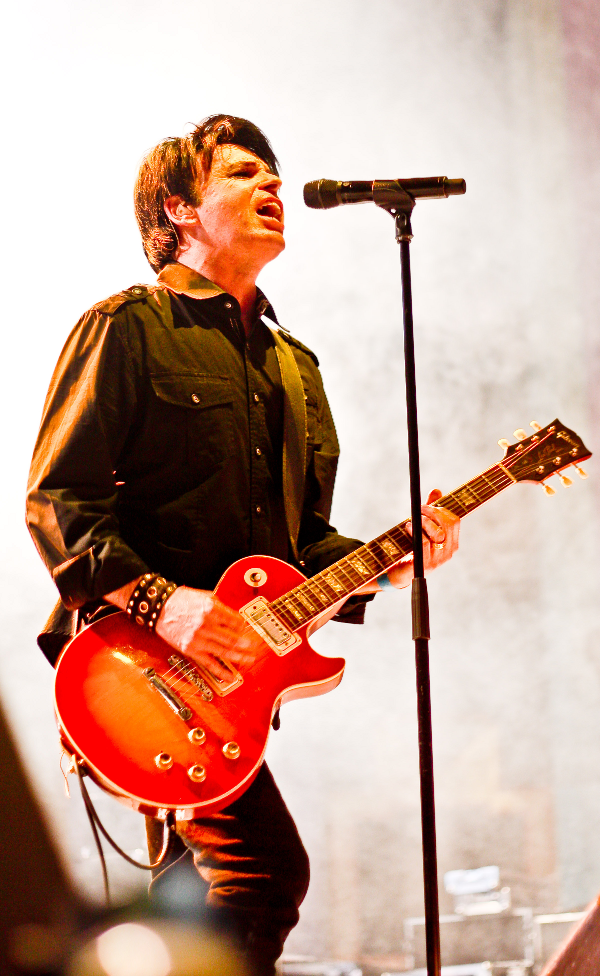

And so, the final course in this musical feast is served. Comus are here. Sitting at the back, David Tibet ceases drumming his fingers upon the back of the chair in front and sits bolt upright. Tonight we are to be treated to songs from 1971’s First Utterance album, interspersed with various oddments from the band’s extraordinary career. Now a six-piece comprising Roger Wootton, Glenn Goring, Bobbie Watson, Andy Hellaby, Colin Pearson and Jon Seagroatt, what is immediately apparent from the opening number, “Song to Comus”, is how tight and how powerful the band sound. Given that this is one of only a handful of shows that the band have performed since their awakening in 2008 (following the mere bagatelle of a 36-year hiatus), they could be forgiven for not being a fraction as intense and focussed as this.Yet intense was always Comus’ speciality, and as they work through “Diana,” “Out of the Coma” and “The Return” (played in tribute to Henry Cow’s fantastic Lindsay Cooper, who had played with Comus for a year, and who had passed away only three days previously), it is (thankfully) obvious for all to see that the years have done nothing to diminish Comus’ threatening force. True, Roger Wootton’s voice cannot rise to quite the same quivering levels of demented hysteria as in his youth, but this loss has been tempered by the gain of the resonance of age, the songs now acquiring an added layer of growling menace from his lower register.

Seemingly aware of this, when introducing the awesome “Drip Drip,” Wootton tells the audience “I’m a nice guy really – if I had friends they would tell you.” Watson, standing to his right, sympathetically corrects this, asking us to bear in mind that Wootton “just had a terrible mind when he was younger.” Wootton’s sublimated rage at his mother may have caused merry Hell to family dinner seating arrangements, but years later we can all still reap the reward of it. During the song, with its beautifully horrible (or horribly beautiful) refrain “As I carry you to the grave, my arms your hearse,” Bobbie Watson’s vocals prove to be as timeless as her appearance, so sharp and clear and beautiful are they. One can only imagine that, like that young Mr Gray, she must have a rather dark portrait locked away in her attic. “The Herald,” the epic second track from First Utterance features some absolutely haunting violin by Colin Pearson, before the closing song “The Prisoner” batters our by now decidedly delicate sensibilities with its pitch black narrative of a mental patient brutalised by electro-shock therapy. Given Comus’ isolation during their original incarnation, both musically and commercially, it is something to celebrated that the band have endured long enough to be able finally to take their rightful place on the left hand path of British music. One senses that the band would love to play on, but the time constraints of the venue (no doubt more restrictive for being part of Islington Town Hall) are against it. Sadly we will not be able to demonstrate our desire for an encore, or indeed several encores (just The Malgaard Suite would do…), but that too has its bright side; perhaps more by accident than by design on this occasion, leaving them wanting more is no bad tactic for any band and, given the incredibly rich experience of the whole evening, it has truly felt as though our cup has runneth over.On stepping back out of the doorway, back into an outside world that seems somewhat cheap and tawdry in relation to what we have just witnessed, there may have been disappointment, yet there is not. I walk home on a complete high.

-David Solomons-