Yes, I confess, during my early teenage years I badly wanted to be David Sylvian. I spent a lot of time standing around nonchalantly beside neo-classical façades, trying to look as though I was on the cover of Oil On Canvas.

Yes, I confess, during my early teenage years I badly wanted to be David Sylvian. I spent a lot of time standing around nonchalantly beside neo-classical façades, trying to look as though I was on the cover of Oil On Canvas.

In retrospect, I blame Ruth Asher. She was several years older than I, and back in the early Eighties was often to be seen around town sporting a distressed black leather jacket with Japan’s distinctive red shūji logo emblazoned striking across the back. I thought she was the coolest thing I had ever laid eyes on. And I was desperately in love.

As a result, and looking for some conversational “in”, I quickly decided that I had better acquaint myself with the band and their oeuvre PDQ.i Not knowing my Japanese arse from my elbow at the time – and this being the days barely of the ZX Spectrum, let alone the internet – I plumped for the first album I could find which featured the aforementioned logo on the cover. It turned out to be Quiet Life,ii the band’s transitional, magnificent third album. And so, whilst my initial motivation for engaging with the band was, to be sure, rather shallow, I very quickly developed a genuine love for them. Going backwards from Quiet Life took me into the raucous cross-genreiii post-glam of the first two albums, whilst their more contemporary material proved to be strange, deconstructed Far Eastern-inflected electronic melancholia. Japan’s catalogue was truly a bounty of riches, yet, sadly, the clock was already ticking towards their (slightly acrimonious) demise at the end of the year.

Following’s Sylvian’s nascent solo career, the next couple of years would prove to be intriguing ones. First came the next instalment of his on-going collaboration with Ryuichi Sakamoto, the utterly beautiful and captivating “Forbidden Colours” from the soundtrack to Nagisa Oshima’s film Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence (and it went top twenty, don’t you know…) and, the year after, his first solo album proper, the utterly glorious Brilliant Trees. The album, together with the single “Red Guitar” (which I had on a picture disc (!) so thick you could use it for tractor wheel) were played, quite literally, to death during the summer of 1984. In an era when the paradigm shift in studio equipment engineering techniques often seemed to be sucking the life out of even the most creative musicians, Brilliant Trees sounded thrillingly vibrant, sophisticated and at the same time somehow off-kilter. And across it all was Sylvian’s haunting, tremulous vocals, like a cool breeze playing through the leaves of the trees on the cover photo. Jesus, even Smash Hits rated it eight out of ten!

The roster of names on the album was, to put it mildly, impressive: former band-mates Steve Jansen and Richard Barbieri, Sakamoto (natch), Danny ‘The Bass’ Thompson, trumpets legends Kenny Wheeler and Jon ‘Fourth World’ Hassell, and crème de la bollocks, Holger Czukay. It wouldn’t be until early the following year, though, when I forked out the requisite £3.29*iv for an Our Price copy of Soon Over Babaluma that I would start to absorb and understand Czukay, Can and their respective place in firmament of musical legend.

Over the following successive years, three more inspired solo albums appeared on the bounce, this time with the likes of Robert Fripp and Bill Nelson also chipping in. Looking back, for a man sometimes sniffily dismissed by critics as a cut-price Beckenham David Johansen only six years previously, Sylvian was already far-outpacing their limited understanding, staking out a hugely unusual territory at the edge of the pop avant-garde and collaborating with those whose own monumental talents he could somehow manage to successfully gild his lily with. As Euripides said, a man is known by the company he keeps…Sylvian’s transition from eyelinered glam rocker to wandering sage was not entirely unexpected to the faithful, though. As the decade had progressed, Sylvian – often decidedly awkward with the trappings of fame at the best of times – had spent ever more time in contemplation and spiritual reflection. And inevitably, as his interior life began to change, so too did his musical one. As Sylvian himself later commented, “…when you get older and realise the hollowness of the whole thing, you think you might as well do something of value or not bother”.

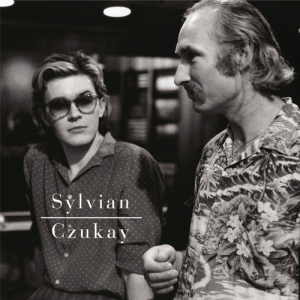

Yet in early 1988, a release appeared which managed to wrong-foot even the most seasoned Sylvian-watchers.An avant-garde collage of improvisation and found sound? Two lengthy tracks, each over fifteen minutes? And no vocals? Yes, all of the above. Again, I say yes.The genesis of Plight & Premonition had actually come two years previously when Sylvian had pitched up at the Can studio – a former cinema in Weilerswist, on the outskirts of Cologne – ostensibly in order to record a vocal for Czukay’s forthcoming album Rome Remains Rome. On a freezing midwinter night, as Sylvian was improvising on the various instruments lying around in the studio, Czukay would surreptitiously record his playing, stopping when he began to consciously shape his playing into formal pieces: “…[Czukay had] only wanted the process, the uncertainty, the ambiguity of searching out new ideas”. With Czukay playing orchestral samples through the studio’s foldback, Sylvian reported falling into a near trance, and far away, in his strange near-hypnogogic state, Sylvain produced a truly extraordinary performance. It was this automatic peregrination which would form the piece “Premonition”: raw, spontaneous and unedited. It was, said Sylvian, “…a form of music that seemed to have been created whilst we were absent by instruments abandoned to the earth and the woods, surrounded by coarse winter elements”.

Stopping only at dawn, the process was repeated the following night, inevitably as a more consciously constructed piece, Czukay working on the Can bricolage model of assembly, and adding piano and flute samples. The fruits of this labour became the opening half, “Plight”.It is surely no co-incidence that, more or less in parallel, Mark Hollis, another wounded veteran of the early Eighties New Romantic wars, was also seeking musical sanctuary in exploration. Driving his band Talk Talk relentlessly out against the stultifying centrifugal forces of the music industry, almost as an act of will, Hollis took them from opening for Duran Duran at the decade’s start to, by its end, producing two albums (Spirit Of Eden and Laughing Stock) that today many people regard not only as amongst the decades’ finest, but as amongst rock music’s finest full stop.

Two years later, at the very end of 1988, Sylvian returned to the Can studio to collaborate with Czukay once more. In the intervening years, though, things had changed considerably. The studio itself had undergone a something of a modernisation, being refitted with both a new mixing console and all-new lighting. Sylvian’s inner life had endured something of a refit, too. During his first solo live tour, an eighty-date international colossus that straddled the globe from Los Angeles to Tokyo, an incipient personal crisis had begun to gain momentum within him. After such an exhausting and, in his own words, “dispiriting” period, the return to Weilerswist allowed him some measure of escape, freeing his creative spirit again. He shared the burden with Czukay, his two erstwhile Canmates – Michael Karoli on guitar and percussion legend Jaki Liebezeit on hand-drum and African flute – and trumpet player and composer Markus Stockhausen, son of the fabled Karlheinz, on flugelhorn. With this stellar cast onboard, Sylvian then recorded two further extended fifteen- to twenty-minute pieces, “Flux” and “Mutability”.

And make a compelling package they do. Plight & Premonition, though contained in terms of decibels, feels wild and free. From low drones and skeletal piano, to found sounds and distant voices, it feels both timeless and at the same moment, like some mutant product of a Cold War Radio Free Europe, Czukay’s Morse code overlays reminiscent of a NATO short-wave broadcast.vi Being both a self-contained world of its own and, in retrospect, a marker of a historical juncture between times – the fag-end days of a wintery, pre-unification West Germany and the brave new world of the Wiedervereinigung – hearing it again it reminds me now of Chris Petit’s luminous masterpiece Radio On, made a decade earlier in 1979 at the tipping point of the social democratic model into the market-driven frenzy of the Thatcherite 1980s. It would be interesting to see Petit’s film with Plight & Premonition overlaid as the soundtrack – I have a suspicion that they would work immensely well together.

Whatever one chooses as a reference point, if anything at all, this is a deeply gripping album, one to listen to on a February train journey from Bremen to Nuremburg. Knowing the inner crisis which Sylvian was experiencing at the time, one cannot help but hear something of his discontented predicament reflected within the grooves. An aura of spiritual searching permeates the two pieces, “Mutability” feeling at points almost like a lament.Flux & Mutability, whilst sharing its sibling’s creative locus and overall sensibility, possesses a more structured and muted atmosphere. That’s not to sound critical. Far from it. To have made merely a Plight & Premonition Part 2 would have devalued both albums. Instead, Sylvian and Czukay took their original inspiration off into a different direction. As so often within the musical explorations of Can, Liebezeit’s elegant, subtle percussion provides the fulcrum around which the others can pivot. His playing is neither loud, nor complex, nor showy. He does just enough to anchor the piece. Karoli’s delicate bursts of guitar provide little marks of punctuation, again doing just enough and no more, and reminding why his was a special, if often overlooked, contribution to the narrative of the guitar.

In the end, I never did get to go out with Ruth Asher. Instead, though, as a result I developed what was probably a far longer-lasting relationship with David Sylvian. For that, I will be forever grateful.

-David Solomons-

i Pretty damned quick.

ii As a result of seeing Sylvian on the album’s cover, for years afterwards I wore a two-colour tie, leather box jacket and a set of thick plastic bangles purchased for about £1.50 in Dorothy Perkins.

iii “Rhodesia” from the second album, Obscure Alternatives, is one of the few examples of rock successfully incorporating reggae into its construction.

iv Complete with Nice Price cover sticker. The sad demise of Our Price Music was protracted and painful, the final branch to close being the Chesterfield one in 2004. The chain’s remaining stock was then sold to Oxfam.

v In truth, Sylvian’s perhaps more than Hollis’s. With Talk Talk disintegrating before the third part of their contractual trilogy was complete, Hollis recorded his eponymous 1998 solo album to fulfil the legal obligations. Save for a handful of very minor excursions back into music (his piece “ARB Section 1” was used in the Kelsey Grammer television series Boss), he has since been silent. His truly splendid isolation continues to intrigue, though it is said on good authority that he will not discuss his musical past in any way. This is no remote Greta Garbo-like seclusion, though; he is more than happy to have a pint and chat about Spurs.

vi Czukay referred to his signature use of short-wave radio extracts as “radio painting”.