David Wrench received an epiphany while trapped in the worthy nu-folk purgatory of the Green Man Festival last year. Surrounded by polite and twee young indie kids who had discovered acoustic instruments and woolly jumpers, he despaired at how a once radical and iconoclastic social force had been reduced to yet another lifestyle and fashion choice. As synchronicity would have it, at that very moment he received a call from Julian Cope inviting him to record a solo album as part of Cope’s Black Sheep project. Seizing the opportunity to restore traditional folk’s lost edge and to reshape the genre in a manner befitting the 21st century, Wrench immersed himself in texts from previous centuries, eventually settling on a handful of songs that he deemed as resonant today as at the time they were written.

David Wrench received an epiphany while trapped in the worthy nu-folk purgatory of the Green Man Festival last year. Surrounded by polite and twee young indie kids who had discovered acoustic instruments and woolly jumpers, he despaired at how a once radical and iconoclastic social force had been reduced to yet another lifestyle and fashion choice. As synchronicity would have it, at that very moment he received a call from Julian Cope inviting him to record a solo album as part of Cope’s Black Sheep project. Seizing the opportunity to restore traditional folk’s lost edge and to reshape the genre in a manner befitting the 21st century, Wrench immersed himself in texts from previous centuries, eventually settling on a handful of songs that he deemed as resonant today as at the time they were written.

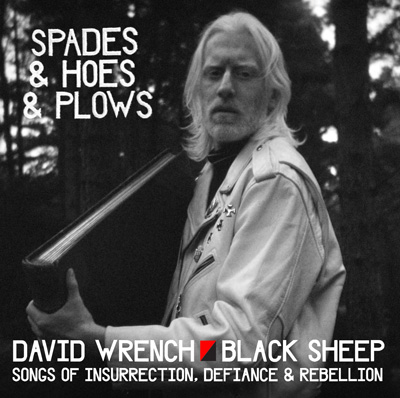

With aid from fellow Black Sheep Michael O’Sullivan, Fat Paul and producer Julian Cope, Spades & Hoes & Plows achieves a deceptively simple soundworld, at once uncluttered and unsettling, Wrench’s ominous voice dry and upfront just so you’re in no doubt that it’s you that he’s addressing. Black Sheep conjure up an appropriate sense of dread, discarding guitars and fiddles in favour of less traditional instruments such as the Mellotron 400 and the Wurlitzer electric piano. The contemporary folk scene’s misplaced notion of authenticity, where surface authenticity overrides authenticity of intent – using hand-crafted 17th Century lutes taking precedence over inciting social insurrection – is completely overturned, resulting in probably the only truly authentic folk album of the century to date.

The dark heart of British folk music has been recontextualised before, most notably by Current 93 and the neo-folk movement they inadvertently spawned. While Spades & Hoes & Plows certainly shares the same apocalyptic sense of foreboding as Current 93, Wrench completely eschews the esoteric mysticism of the neo-folksters’ texts, opting instead for a hyper-direct and unambiguous approach that leaves the listener with absolutely no doubt as to which side he’s on.

Opening number “A Radical Song,” dates from 1816 and does what it says on the packet – a call to violent uprising invoking the relatively recent inspiration of the French Revolution and understandably omitted from the trad-folk revival canon, its lyrics presaging black metal by a good 170 years:

The priest must be hanged and the bibles all burned,

Under your feet your enemies tread

For fear qualms of conscience from them should be learnt.

Now is the time for blood to be shed.

The song inches forward at a glacial pace for almost ten minutes, and is the shortest track on the album, leading as it does into an epic 24-minute version of the more well known “Blackleg Miner.”

It’s a sign of how much folk has been emasculated in recent years to remember that as recently as the mid-80s, Steeleye Span – a group who had chart hits and were never considered exactly radical – performed this song in front of an uncomfortable Nottingham audience at the time that the local miners had just broken the national strike and done a deal with Thatcher. With the song’s call to “Catch the throat and break the spine of the dirty blackleg miner,” it’s a testimony to how committed even the more populist end of the folk world used to be that they didn’t flinch from playing the song in the very home of the song’s targets.

Wrench again takes the song at funereal pace, singing the entire song acappella before introducing a repetitive distorted electric piano riff that wouldn’t be out of place on an Earth album. The song is then repeated over Mellotron and glockenspiel. Another interlude, this time of dissonant accordion atmospherics leads into a third reading of the verses, this time to swirls of electronic noise and a simple reiteration of the vocal tune on the Wurlitzer. A disquieting coda of harmonious Mellotron chords disturbed by creaking effects and rasping cello brings the song to a close. After 24 minutes, you can tangibly feel the weary yet undiminished resolve of the miners to stand together.

A reading of proto-Marxist Gerrard Winstanley’s “A Diggers Song” from 1649 follows – a call to arms again advocating violence against clergy, lawyers and gentry. The song is driven by Cope’s 26” marching bass drum, with Wrench and the rest of the Black Sheep exchanging call and response vocals. Detuned Mellotron interludes unsettle the mix and ensure that the song doesn’t degenerate into the kind of inane rabble-rousing anthem so beloved of Winstanley’s other contemporary fans, the loathsome Levellers.

The album ends with “Helyntion Beca,” a group-penned instrumental in tribute to the Rebecca Riots of 1839-1843, where south Wales’ tenant farmers rebelled against paying tithes to the Church of England, while dressed as women. A narcotic piano riff slowly unfolds, weaving through sinister rumblings, the tension building incrementally for a full fifteen minutes before exploding into thunderous percussion as the toll gates are smashed to the ground.

It is perhaps no coincidence that Spades & Hoes & Plows‘ arrival coincides with that of a new Tory government – never has there been greater need for a re-radicalisation of popular culture. In much the way that Fairport Convention reset traditional British folk to stand up for itself in a culture dominated by The Beatles and Jefferson Airplane, David Wrench has managed to make a traditional folk album that sits happily alongside Sunn O))), Acid Mothers Temple and Burzum. As such, Spades & Hoes & Plows is the most important folk album since Unhalfbricking.

-Alan Holmes-