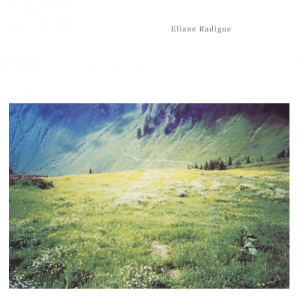

Éliane Radigue‘s Geelriandre / Arthesis loves time, luxuriates in it. Its frequencies gradually slip its grasp, or your perception, in that slow luxuriating bend to the goods that eats into your consciousness, subliminally cuts, the eerie exponentials creeping up on you like the textural dance of a Max Ernst painting. Solemn, solar, tumouring an odd timbre that percussively curls on tight jewels of Cageian prepared-ness from Gérard Fremy, with rubber-softened and plucked piano strings that solitary chime, cluster in doppleganging recoil to puncture the meditative continuum.

Éliane Radigue‘s Geelriandre / Arthesis loves time, luxuriates in it. Its frequencies gradually slip its grasp, or your perception, in that slow luxuriating bend to the goods that eats into your consciousness, subliminally cuts, the eerie exponentials creeping up on you like the textural dance of a Max Ernst painting. Solemn, solar, tumouring an odd timbre that percussively curls on tight jewels of Cageian prepared-ness from Gérard Fremy, with rubber-softened and plucked piano strings that solitary chime, cluster in doppleganging recoil to puncture the meditative continuum.

Recorded at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam in December 1979, this first track “Geelriandre” (realised seven years before) is blinding. A few coughs give you that all important live context, but don’t spoil the feast, as the sound sizzles with the spiritual, has you knotted in its infinite otherworldly expanse. A perfect antidote to the festive excess you might say, caught in the rubbed rim of a wine glass.

When most musicians were embracing the modular synth’s obvious sci-fi leanings, Radigue looked beyond, became seduced by the tonal possibilities of feedback most composers were trying to eliminate, searching for the great in the small, trapping its essence in lengthy tape loops. No doubt studying electroacoustic music with Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry had given her a firm foundation and opened her ears, to strip away the decorative frills and take things to a whole new Zen-like level. A deep listening aesthetic that directs you inward, blocks out external troubles, very much like the Buddhist doctrine she would later adopt, a slow unfurling of delicate harmonics that pull you outside of time’s grip — the ultimate reward of the drone. An iridescence the second track “Arthesis” (conceived somewhere around 1973) mutates into sinistral shapes. The yin to the other’s yang, a rumbling vibrancy, be-speckled in contrasty contours. Only up until recently have we actually heard the eeriness of the great beyond, sounds vibrating in the great vacuum of space, but this seems to have beat the scientists to it by a few decades. A mysterious vibe that would later (subconsciously) seep in the majesty of Coil’s “How to Destroy Angels”, or be re-explored in Steve Stapleton’s Soliloquy for Lilith. Like a short-wave radio signal from a dying star that here draws itself into the notching elastic of a grandfather clock’s mechanism, the reverberating ripples disappear into a deafening silence that created them.-Michael Rodham-Heaps-