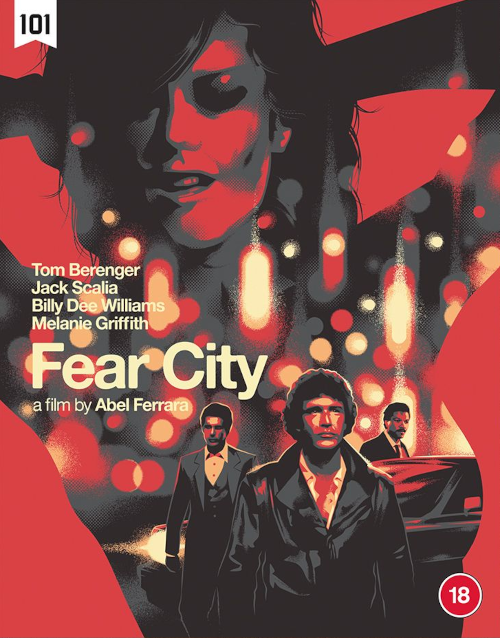

A re-release of Abel Ferrara’s Fear City finds the cult classic from 1984 as interesting in its flaws as ever.

A re-release of Abel Ferrara’s Fear City finds the cult classic from 1984 as interesting in its flaws as ever.

It’s the mid-’80s, New York is pre-clean up, still a landscape of neon, sex and hovering violence. Former Boxer Matt Rossi (Tom Berenger) and his business partner Nicky (Jack Scalia) run a management company for Manhattan’s best strip club dancers.

Then the women start to be brutally assaulted and killed by a mystery assailant, bringing the attention of hard-nosed Detective Wheeler (Billy Dee Williams) and Matt’s own investigation into a mire of violence, misogyny and paranoia. Complicating things further is Matt’s on-off relationship with his star performer Loretta (Melanie Griffith), as well as his guilt from a fight gone wrong that ended his career.

As much as that sounds like a film noir, the film is never a mystery. We know early doors who the killer is; we watch him do his absurd naked martial arts and hear the ramblings of his diary in a performance that has a real pang of Buffalo Bill nearly a decade prior. If there’s one thing director Abel Ferrara isn’t really interested in it is plot, narrative being only part of the picture in making a grander, all-consumingly salacious urban tableau.

It was Ferrara’s first film for a major studio, but the clash between the studio’s desire to make an exploitation thriller and his desire to make something more shows pretty heavily. For every piece of formal daring that is employed there is a decision that comes completely out of nowhere. You can almost see the producer, cigar in mouth over their shoulder going “Get back in the club! Show them the girls! Y’know what would’ve make that Taxi Driver movie less boring? Samurai Swords!” It’s a Ferrara film and even at his best he is not a film-maker who makes films you ever exactly enjoy. Bad Lieutenant is still an incandescent horror, even as its cruelty truly unlocked Ferrara’s baroque brilliance. But this is no Bad Lieutenant. It’s shoddier in pretty much every aspect. The characters are more formulaic, the plotting more predictable, its screenwriting lazier. The performances run the gamut from hammy to uninterested.Berenger’s face is perfect for the role; he’s got movie star appeal but is rugged enough that he’s a viable low-level heavy. But, crucially, when he’s meant to carry any emotional weight, it falls down. His perennial frozen expression isn’t a Bogartian blank canvas that seems to hold a multitude of hidden sorrows; it’s just vacant, verging on gormless. Michael V Gazzo on the other hand (his second 101 Black Label release in a row) is basically born to play a callous strip club owner, more worried about his takings than his murdered dancers, and does so perfectly.

But despite all this, the film does have something about it. The world Ferrera’s usual screenwriter Nicholas St John writes is a cruel one; racism and misogyny abound and even our heroes are a long way from heroic. Matt is emotionally non-existent and pretty vile to Loretta, and Williams’s cop has a vengeful piety, while just about every other word out of his mouth is an anti-Italian slur. Its nihilism is ferocious, but, like Ferrara’s later films it has a point beyond pure exploitation.On the one hand there’s a horror of the city itself: its shadowy alleys, its streets littered with smashed bottles and rain-soaked newspapers all throb with violence and hopelessness. But it’s a film that understands that there is a seductive power to the city too. Fear City spends a long time in the clubs, it’s obsessed with bodies and pleasures of the flesh, and paralleling them with uncomfortable, vaguely fetishistic violence. It uses this exploitative quality to interrogate itself and the viewer, to question complicity.

It’s the kind of thing Harmony Korine was getting called a visionary for years later, but more committed to its genre trappings and with none of the smug irony. In its frequent nods to religion, Fear City looks at the clash of depraved humanity with divinity, whilst containing an acceptance of this as an inevitability, that this conflict is essential to the human experience. It is a point Ferrara would make time and again throughout his career, usually with far better films, but it is interesting to see it in such embryonic form.Perhaps I’m giving it the benefit of the doubt because of Ferrara’s later work, but it feels like a film slightly out of time. It’s too late for the scuzzy nihilism of ’70s New York, too early to be the underbelly of Yuppiedom. The Ferrara and St John team is far from the finished article at this point. It’s not that they ever really made a perfect film together (St John famously opting out of Bad Lieutenant on religious grounds), but here they are yet to hone their ideas and execution to what would make the pair so endlessly interesting.

Yet the film still retain a certain something, a curious clashing of styles that makes it strangely captivating despite itself.-Joe Creely-