London

23 October 2015

Can you imagine how hard it was being Gary Numan in 1989? A decade earlier, shortly after “Are Friends Electric?” had been released in May 1979, Tubeway Army made their triumphant appearance on Top of the Pops, and the sound of a generational gasp could be heard all the way from Truro to Inverness. Punk’s white light had burned away so much dead wood, reinvigorating youth culture and opening the door for those with the boldness of vision to step through it. Now, a new dream of futurism seemed completely embodied in Tubeway Army’s woozy Polymoog synth wash and Numan’s cold, android stare. Like the Apollo space programme earlier in the decade, Numan’s emergence into the musical firmament promised a new dawn that felt so close you could almost reach out and touch it.

And that dawn needed Numan. The new electronic music had been bubbling away for some years, through Kraftwerk and La Düsseldorf, Bowie, Eno and Daniel Miller. More recently, Ultravox (both with and without their exclamation mark) had conjoined raw punk guitars with a rudimentary blueprint of electro-pop, even doing so under the masterly tutelage of Conny Plank. Yet, to make the next step in its viral evolution, to truly break the mainstream, the new electronic music needed someone to take this sound of the underground and fashion it into solid gold blockbusters, ones which could shift units and insinuate itself into the ears of more than a small coterie of cool music-savvy heads in the rock avant-garde.And Gary Numan was the synthetic humanoid for the job. Bowie may have been peeved – famously having Numan chucked off The Kenny Everett TV Christmas Special and commenting to Record Mirror that “I never meant cloning to be part of the Eighties” – but the gleaming chromium truth was that Numan was out-selling his former hero four to one. And whilst the mainstream music press might have followed Bowie’s line, sniffily distaining Numan’s output as that of a mere arriviste, John Peel, the touchstone of the era (of several eras), knew better, stating that “I must confess I do allow myself the occasional snigger when I consider that Tubeway Army are at number two in the charts because their records have been almost universally slagged off by the critics and we’ve always played them on these programmes. How smug we get on occasion.”

At the end of the decade, he was a faded memory of a future that never was, filed away alongside the silver spacesuits of the Mercury 7 or the bionic eye of Steve Austin. If the media mentioned Numan at all, it was to sneer at his youthful enthusiasm for Mrs Thatcher or relate with acid schadenfreude the tale of him crashing his airplane on the motorway near Southampton (erroneously in fact, as Numan had only been the passenger, not its pilot). And despite his love of planes and stunt pilot qualification, his wealth too had evaporated, Numan later recalling to the Guardian that “I was in big trouble. I needed to make some money quick, but at that time no one liked what I was doing. The radio stations weren’t interested, my record company thought I was rubbish, and the media hated me. I released one single that sold just 3,000 copies. You really have to adapt to that.” Rock bottom. The man who had so represented the future seemed to have none of his own left.

For Numan, the Nineties began more or less where the Eighties had left off, forced to propel his tiny kayak around Shit Creek using only his hands. 1992’s execrable album offering Machine + Soul seemed to confirm only that there was no way back. Marty McFly might have made it back in a gleaming DeLorean, but not so Gary Numan. Yet, almost imperceptibly, a change had begun to happen, and the mile-thick layer of permafrost that had settled over Numan’s career began to melt. New black-clad American stars such as Nine Inch Nails, Foo Fighters and Marylin Manson began to sing his name in praise a key influence and invite his participation. More amazingly still, dance and pop also began to get in on the action, raising high the Numan standard once more: Basement Jaxx sampled The Pleasure Principle on their 2002 smasheroo “Where’s Your Head At?” (I remember that damned gorilla being everywhere), and – Christ – The Sugarbabes’ 2001 “Freak Like Me” cover used “Are Friends Electric?” as its RSJ underpinning. Let’s rebuild the past, as the future won’t last. Suddenly, like Dracula risen from the grave, Numan was back. And in that renaissance, not only has he clung on, he has flourished.*

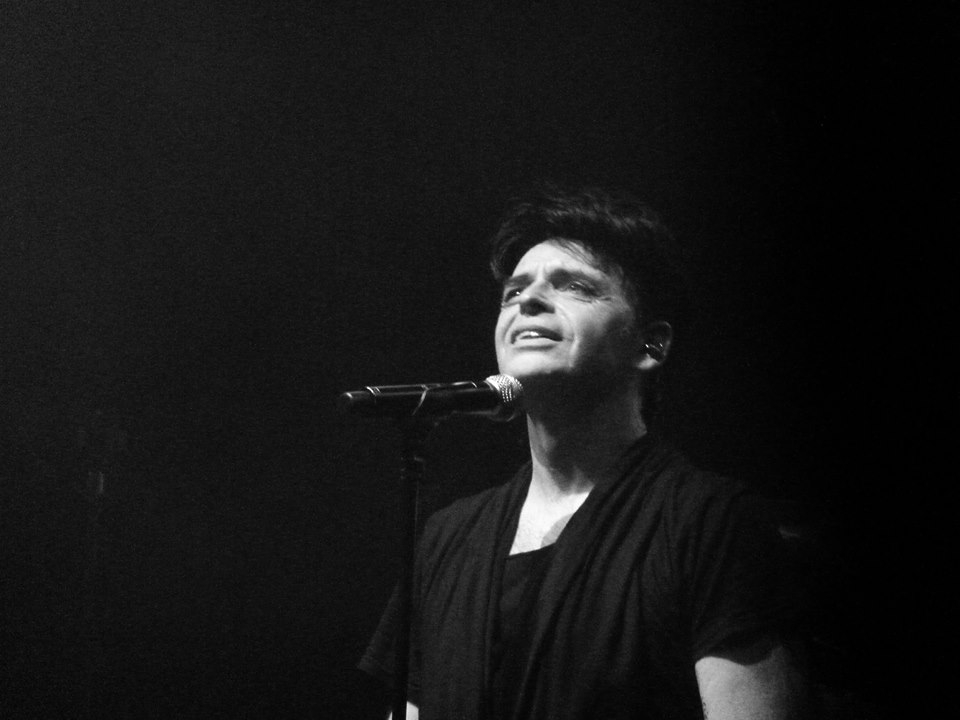

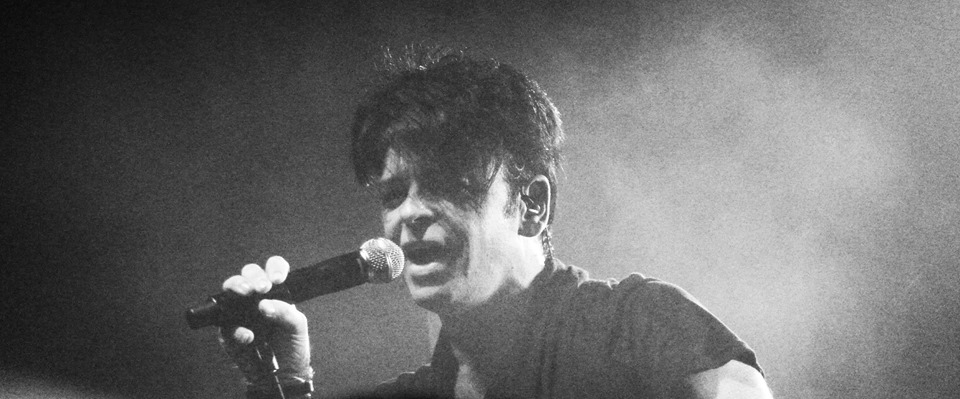

And so, here in Kentish Town, Numan finishes his run of three evenings revisiting the glorious albums of his first, meteoric Machine period in all their newly re-adored beauty. Tonight it’s the turn of 1980’s Telekon, for many the high watermark of his (early) career. Kicking off with the gloomily inappropriate single “This Wreckage”, Numan and the band fair tear through the dystopian dreams of Telekon’s material like their lives depended on it. As a picture of the youthful Numan’s gazes down at us from a white light triangle set within flashing the neo-Constructivist red stripes of the album’s cover, we are treated to every one of the album’s delights, from a sublime “Sleep by Windows” to a ferocious “The Joy Circuit”. Additional gems such are thrown in at no extra charge: “We Are Glass”, “I Die, You Die”, “Cars”, “Metal”.

I’ve never been one to be overly impressed by lightshows, but this evening’s is so artfully constructed – huge blocks of mono-colour pierced by sharp pillars of white light – that the swirl of colour and sound is hugely effective. It’s loud, but even the band’s amplification cannot mask the fanatical chanting of “NU-man, ‘NU-man” that starts up every time the merest sliver of quiet makes itself apparent. These are no Johnny-come-latelys, drawn on a curious whim by Numan’s influence on bands they like, nor ageing neophytes come to goggle at the man who shaped their vision of what the future would hold back in the days when flares and brown and brown flares still held sway across old Albion. No, these are the faithful, the hardest of the hardcore, those who have never lost faith in their hero, not even in his darkest hours. No Crass following could ever have been more devoted than this. NU-man! NU-man!

Predictably the audience greets this as though it’s an invitation all back to Gary’s and he’s laid on beer and Pringles. The faithful are in raptures, and I fear that finally, after decades of gig-going, after having survived Swans and My Bloody Valentine and Sunn O))) and – most terrifying of all – Pussy Galore, my long-suffering eardrums will finally be punctured not by Tower of Babel sized Marshall stacks and immensely overdriven Fender guitars, but by frenzied hoards of Numanites screaming “NU-man! NU-man!”

Numan himself first sings along, then conducts the chanting and finally stands, arms extended, messianic and back-lit, riding the moment and what must seem for him like the end of the longest road back, like real redemption. And when he’s ready to begin “Everyday I Die”, he is unmistakably wiping away tears. Maybe in 1989 he dreamed of one day crying like this.*

Back in the late 1970s and early 1980s, whatever levels of opprobrium Bowie and the music press might have tried to direct his way, Gary Numan made the most superior electro-pop, music that influenced more people – in ways large and small – than I could shake a stick atiii It’s easy to forget how completely and utterly burned out Harold Wilson’s empty promise of the white heat of technology was by the end of the 1970s. Gary Numan, even if only briefly, became a vessel in which, through which, such dreams could be heaped and enjoyed anew. He then spent decades in the wilderness trying to come to terms with that.

We live now in times when futurism seems as vanished and historic as Sopwith Camel biplanes or the BBC Light Programme – the promise of Apollo 11 shrunk to the next upgrade of Android or an app that can control your boiler thermostat from the bus home. What happened to our dreams of the future?Perhaps popular music sums this up as well as any other example. The old expectation was its endless exponential growth, a whole-regeneration change-and-renewal once every two or three years, The Beatles racing from innovation to innovation so fast even they could scarcely keep up. Such expectation now seems as unbelievable as Gene Cernan racing across the Taurus-Littrow valley in the lunar rover. One of the benefits of our newly-contracted musical hopes, though, is that those once condemned to wander the limbo of the musical past can be readmitted once more and re-admired for their previous, and authentic, contribution. And Gary Numan can now benefit from this more profoundly than most.

2015 may be more Basingstoke than Blade Runner, but there’s thankfully a place for Gary Numan in the collective heart once more, and space for him to demonstrate again why he deserves to be there.The future’s bright – the future’s 1979.

-Words: David Solomons-

-Pictures: Cheryl Booth-

-Video: Medwyn Jones-

i From An Ideal Husband.

ii Even in space any vision turned from exploration to militarisation, Ronnie Reagan’s revolting “Strategic Defense Initiative” being the prime inter pares example.

iii And I can shake a stick at a lot of Numan-influenced people.