Right from its first publication in February 1911, the novel Fantômas was a phenomenon. In the words of post-modern New York über-poet John Ashberry it was “a work of fiction whose popularity cut across all social and cultural strata. Countesses and concierges; poets and proletarians; cubists, nascent Dadaists, soon-to-be Surrealists: Everyone who could read, and even those who could not, shivered at posters of a masked man in impeccable evening clothes, dagger in hand, looming over Paris like a sombre Gulliver, contemplating hideous misdeeds from which no citizen was safe.”

Right from its first publication in February 1911, the novel Fantômas was a phenomenon. In the words of post-modern New York über-poet John Ashberry it was “a work of fiction whose popularity cut across all social and cultural strata. Countesses and concierges; poets and proletarians; cubists, nascent Dadaists, soon-to-be Surrealists: Everyone who could read, and even those who could not, shivered at posters of a masked man in impeccable evening clothes, dagger in hand, looming over Paris like a sombre Gulliver, contemplating hideous misdeeds from which no citizen was safe.”

As Ashberry here makes explicit, the singular success of the novel – put together by two hack journalists Marcel Allain and Pierre Souvestre in response to a commission by publisher Arthème Fayard – was characterised by its complete transcendence of any notions of high and low culture. Not only was it a gargantuan popular hit, but the daring and fabulous exploits of sinister master criminal Fantômas also snagged the undying love and admiration of a truly incredible cross-section of the era’s leading artists and writers: Guillaume Apollinaire, Jean Cocteau, Max Jacob, Pablos Neruda and Picasso, James Joyce and René Magritte. Blaise Cendrars went so far as to call the series “a modern Aeneid.” In short, it was not lacking a powerful admirer or two.

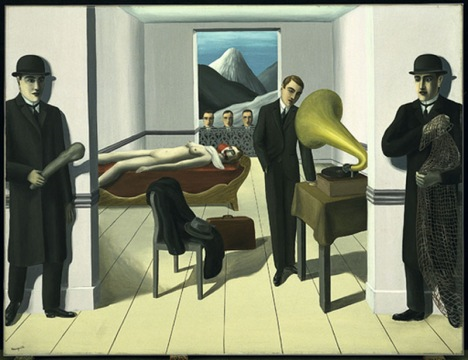

My own introduction to the cult of Fantômas came in the mid 1980s as a result of seeing Magritte’s 1927 painting “The Menaced Assassin,” in which Fantômas, under the seemingly-unseen scrutiny of five armed police detectives, casually listens to an old gramophone, the naked body of his victim mere feet away, a scarf wrapped around her throat and a hideous smear of blood oozing from the corner of her mouth. Fantômas may have been a violent sociopath who murdered with seeming impunity, but there was no doubting his nerves of steel.As it turned out, in this bold and startling canvas Magritte had actually referenced a still from the first of a series of five film adaptations made by silent film pioneer Louis Feuillade in 1913, not long after the novel first appeared. Now regarded as masterpieces of silent cinema, each one of the films ends with a nail-biting cliffhanger – could arch-foe Inspective Juve and tenacious young reporter Jérôme Fandor really have been blown to smithereens by Fantômas’ bomb..? And it was to a screening of the fifth instalment, Le Faux Magistrat, showing at the Théâtre de Châtelet in Paris on Hallowe’en 2013 as part of a celebration of the series’ hundredth anniversary, that English guitarist James Blackshaw was invited to contribute the live soundtrack, now being released here by Tompkins Square.

Although Blackshaw’s intricate style of acoustic finger-picking has, in the past, drawn comparison with the likes of Robbie Basho and John Fahey, his recorded output is significantly more varied than that might suggest; a single listen to anything by The Brethren of the Free Spirit (his duo with Dutch minimalist composer and lute player Jozef van Wissem) will attest to that. Here, ably assisted by composer and guitarist Duane Pitre, multi-instrumentalist Charlotte Glasson and Slowdive’s Simon Scott on drums, Blackshaw produces a beautifully-crafted score which moves freely and elegantly between a wide array of atmospheric and unsettling movements.From the moody, noir jazz of the opening segment, to the delicate, almost Rothko-like ambience of the second passage, to accomplished and unadorned bursts of acoustic guitar, there is a delightful interweaving of styles and textures and humours that never feels out of balance or threatens to overwhelm. Later, with drums pounding, quivering vibes and saxophone managing to remain just a hair’s breadth within the tasteful side of skronk, it’s a powerful palette with which to paint modern audiences a soundtrack to an early masterpiece of cinema, one now unbelievably a century in the past.

A fifteen minute section of the performance, filmed from the orchestra pit, is currently viewable online, allowing those who were not lucky enough to be in the Théâtre de Châtelet that night to see how Blackshaw’s musical vision matches up sympathetically with the film, bringing out its tensions, its Edwardian sophistication and its proto-Lynchian sense of Surrealist mystery.

As James Joyce might have put it, enfantomastic.

-David Solomons-