Against the backdrop of a 2023 which brought a BFI retrospective, and what looks to be his late career masterpiece, EO, comes this release from Second Run of three of Polish auteur Jerzy Skolimowski’s key early works. They show a truly forward thinking director, whose work from this era remains relatively under-seen compared to his contemporaries, despite it containing some true classics of the European new wave.

Against the backdrop of a 2023 which brought a BFI retrospective, and what looks to be his late career masterpiece, EO, comes this release from Second Run of three of Polish auteur Jerzy Skolimowski’s key early works. They show a truly forward thinking director, whose work from this era remains relatively under-seen compared to his contemporaries, despite it containing some true classics of the European new wave.

Having already been a published poet and co-written two of the Polish new wave’s great films by his mid-twenties (Roman Polanski’s Knife In The Water and Andrzej Wajda’s Innocent Sorcerers), Skolimowski was already something of a prodigy by the time Walkover (Walkower), the first film in the boxed set and his second feature, was released. The film acts as a loose sequel to his debut Identification Marks, following the same character of Andrzej Leszczyc, an alter ego for the director, as he navigates his mid-twenties, buffeted about by a society he and his generation is increasingly at odds with.

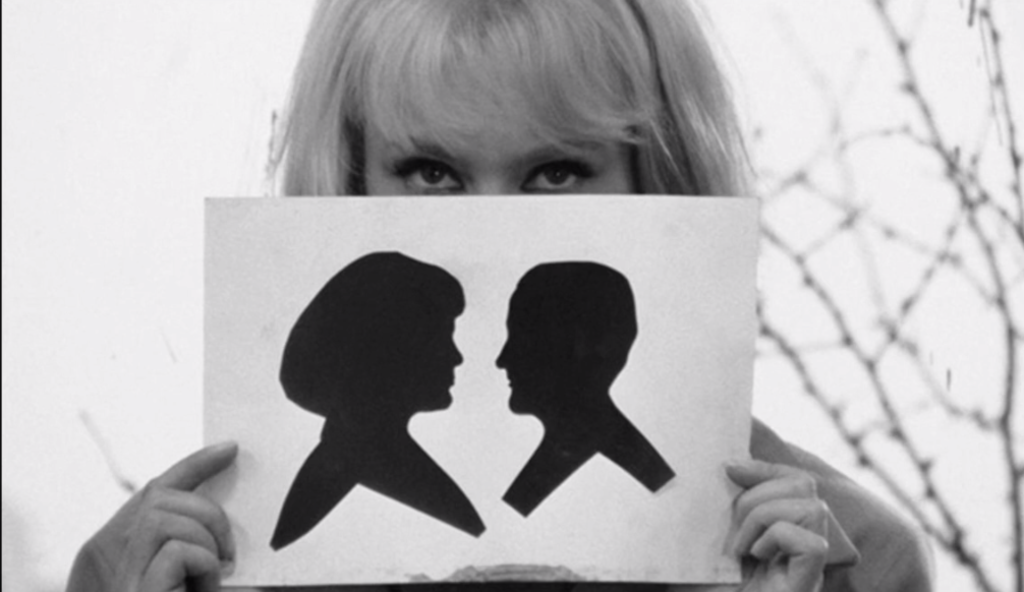

While this doesn’t make for a captivating synopsis, like much of Skolimowski’s work the film’s joy lies in its style. It largely consists of long takes, but rather than any sort of Slow Cinema-style meditative pacing, Skolimowski constantly fills the frame with little visual details and sly jokes. It creates a brilliant wonky tension. There is a formal energy trapped, as the characters are, in this grey landscape of factories and confusion. This central tension, and his presentation of the fundamental tension at the heart of youth in the Warsaw Pact countries, is what made him a key figure in Polish youth culture, but it is with his next film that he perfected it. Barrier (Bariera) remains after all these years Skolimowski’s masterpiece and his most recognised work. It found him energised by his time at film festivals with Walkover, and this engagement with the contemporary explosions of invention across European cinema pulses throughout. It is a work that contains a formal joy to it and excitement for the potential of the form that few films can match, no second allowed to pass without a narrative left turn or a trick of the camera. However, miraculously, it never grates, never becomes showy, resisting the directorial jazz hands that many films inspired by the European new wave fall into. The narrative is slight, an excuse for a constantly upended series of incidents, more like sketches than scenes, but with a kind of cumulative giddiness that makes it an incredibly affecting work, worth getting the boxed set for alone.A special mention must go to Michael Brooke’s commentaries on both Walkover and Barrier, which he presents at such breakneck pace and with such density of information that they manage to mirror the experience of watching the films. Your head is spinning by the end with the full life stories of people who have one line and insightful social histories of the era Skolimowski was creating in. He also provides a key bridge between the short films on offer and the later work, detailing how Skolimowski went from the interesting, but clearly far from spectacular works he was making in the early sixties, to these later masterpieces.

Dialogue 20 40 60 (Dialóg 20-40-60), while not to the standard of the solo features he was releasing around the time, makes for invaluable context for Skolimowski’s place amongst his contemporaries. The film’s central conceit consists of the same dialogue, spoken by couples of three different generations, and helmed by three separate directors.Skolimowski’s role as spokesmen for the youth led to him directing the first segment, and if anything rather upending the film. His breakneck style stretches and mangles the potential of the script more than any other filmmaker. As such, the rest of the film feels comparatively lifeless. Co-directors Peter Solan and Zbyněk Brynych do a perfectly engaging job but the film, but their sections can’t help but feel staid once the freewheeling energy Skolimowski brings is replaced by their more traditional approaches. It ends up feeling rather like a joke told backwards.

The censoring of the 1967 film Hands Up! for its examination of Stalinism led to Skolimowski moving away from making films in Poland for the next few decades. There are great examples from his time in more commercial films, particularly the magnificently peculiar The Shout, but none contain the era-channelling energy of his early works. These three features make for a strong reminder, or potential revelatory experience, of the brilliance of the early works of the European new wave’s true underused talents.-Joe Creely-