There are few creatures more misunderstood than the fox.

There are few creatures more misunderstood than the fox.

Wankers hunt them, city-dwellers either leave food out for them or moan about them getting into the bins, dogs love to anoint themselves with their shit, we name attractive people after them, we name sly and devious people after them, rockers like Rob Zombie name songs after them and on the internet they name browsers after them.

Hell, Kojima loves them, and Kojima doesn’t love ANYTHING that’s simple. Because the fact is, people are very fond of saying “things are not what they seem”, but it’s not really true, is it? The vast majority of things are indeed what they seem — it’s just that very few of them are ONLY what they seem.Take John Nettles, for example. You, like me, may mainly think of him as Bergerac, or Steven Toast’s flatmate, or, if you’re VERY like me, or even more so if you’re literally, like, me, as Peter de Leon in Robin Of Sherwood. Or someone off Midsomer Murders (idk, I never watched it). And all of those things have a certain campness to them — in the case of Toast it’s deliberate, in Bergerac and Robin it’s an inevitable function of nostalgia — but the truth at the heart of it is that you don’t get any of those gigs unless you’re actually good at your craft.

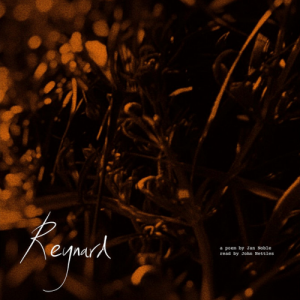

Bergerac was the prestige TV of its day, and the entire joke in Toast of London was that Nettles was a quality performer arguing with the self-aggrandising Toast over breakfast. Which is why he’s an excellent choice to read Jan Noble‘s latest long-form piece, Reynard. I say “read”, but this is a performance. It’s something more than narration, and it’s a world away from that godawful “poetry voice” shit so popular on Radio 4. Nettles inhabits not only the fox himself, but the land in which he runs. (And he runs quite a lot. I mean, he’s a fox).For this is to some degree a retelling of the old European folk tale cycles of Reynard The Fox (see also Julian Cope‘s 1984 classic of the same name — you know, the one that ends with him screaming “AND HE SPILLED HIS GUTS ALL OVER THE STAGE!!!”). Only this time Reynard’s not having shenanigans with the Lollards. This is a thoroughly modern fox, though carrying with him all of history. As anyone who lives in a major city will know, the fox lives alongside us, neither friend nor foe, but mainly a cocky little bugger, a “dog hardware running cat software”, as they’ve been described. Everyone has their trickster figure, whether it be the coyote or the tanuki (otherwise known as “those Japanese racoons with the magic bollocks) and the fox is Europe’s.

Noble’s Reynard is as wise, playful and tricksy as ever, but there’s a noirish modernity to the proceedings, putting one in mind of TS Eliot or Iain Sinclair, with Reynard as the ultimate flaneur, shifting effortlessly from the green of the countryside to the greys and neons of the city, from the terror of the hunt to the tedium of the office. “Let me tell you about Reynard. Put you straight”, the second movement begins, with an air of pub backrooms and dodgy dealings. The ancient lives within the modern, and the fox is at ease with both.

The piece is split into three — we open with Reynard running, setting the scene, then becomes more introspective and abstracted as it goes on. As befits the subject, we leap from location to anecdote to observation, tail wagging and teeth flashing. For all his seeming brashness, Reynard is as subject to human emotion as the rest of us, shedding a tear at death — “Rey was running when the heartache stung / But its poison oiled his vowels… running from the gaining grief” — and ever aware of the precariousness of his existence.

I’m not gonna get into the nuts and bolts of the writing — like music, I tend to think the minutiae of creation are far less interesting than the evocation of feelings, and once you’ve dissected a butterfly you may have a far better understanding of how it works, but you’re never gonna get that fucker to fly again. Suffice it to say there is enough of a strong narrative thread to link all its disparate elements, and the wordplay is excellent, with some lovely imagery: “So long had it been raining / I’d expected the colour to be washed from my coat / to be washed out” — all of which Nettles performs with, and this is not a word I use lightly, or even “at all” in the normal course of things, gusto.I’m loath to use the old cliché of “this is x for people who don’t think they like x”, because it’s usually just basic fucking snobbery, but poetry has a largely undeserved reputation for being something arch, something Roger McGough reads in an annoying voice on a Sunday afternoon, something you were forced to study in school. The problem isn’t that people don’t think they like poetry, it’s that they’ve been taught not to. And this is a perfect example of a piece that anyone could get something out of. As, of course, is most good poetry, if we could only be arsed to look.

Highly recommended. It’s fun, it’s dark, it’s thoughtful, and most of all it’s BEAUTIFULLY written and performed.-Justin Farrington-