London

22 June 2017

Hindsight can be a famously cruel opponent.

Hindsight can be a famously cruel opponent.

On the freezing New Year’s Eve of 1961, The Beatles drove all the way down to London from their native Liverpool amidst swirling snowstorms and treacherous roads. The following day, whilst the nation sipped delicately at some Alka-Seltzer and nursed its collective sore head, The Fab Four fired up their Vox amplifiers and belted out a fifteen-track demo at Decca Studios in the youthful hope of catching the label’s attention. Soon afterwards, though, Brian Epstein received their professional verdict – a curt rejection explained with the now immortal words “We don’t like their sound. Groups of guitars are on the way out.”

Thankfully for the course of music history, Parlophone disagreed with Decca’s analysis and, as the rest of the Sixties would prove, the bulk of the world’s music-buying citizenry liked The Beatles’ sound just fine. The culprit for this stupendous critical misjudgement is usually fingered as Dick Rowe, Decca’s Head of A&R, who with these unlucky thirteen words damned himself forever as a commercial schmuck of truly Biblical proportions. Magnanimously, on listening to the demos many years later, Paul McCartney commented that “I can understand why we failed the Decca audition. We weren’t that good, though there were some quite interesting and original things.”1

Fourteen years later, on 5 September 1975 (three days after Rod Stewart’s blockbuster tartan-scarf-wave-a-long “Sailing” hit the Number One spot), Kraftwerk kicked off their début tour of the UK, playing to a Spartan audience at Newcastle’s Mayfair Ballroom. A week later, Melody Maker ran a sidebar review giving their verdict on the Newcastle show: “Spineless, emotionless sound with no variety, less taste and considering the barrage of equipment on stage, damn little attempt to pull off anything experimental, artistically satisfying or new.”2 And so, with this little burst of opprobrium, did reviewer Keith Ging take his place forever on the podium just beside Dick Rowe.The rest of the tour would roll on through the major metropolitan cities of the UK – Manchester, Glasgow, Birmingham, London, Yeovil (Yeovil!) – with the Liverpool show on the 11th being a particular highlight. Four days later, the aforementioned McCartney would return to his hometown, bringing his Wings Over the World tour to the Empire Theatre, and the vast majority of the music-obsessed locals were allegedly saving themselves for that show, revelling in the chance to welcome back their conquering hero. Only a doughty few seized the opportunity to make a night of it at the Empire in order to see Kraftwerk’s fifth ever UK show (by most estimates only around 300 of the venue’s 2,400 seats were occupied).

One of those that did was Andy McCluskey, soon afterwards the main man behind Orchestral Manoeuvres In The Dark, who recalls with evangelical fervour sitting in “seat Q36”, and that “It was the height of long hair, flared denim and lead guitar solos, and they came out looking like four bank clerks with electronic knitting needles and tea trays. It was like an alien spaceship had landed.” The fact that, decades later, McCluskey can still remember his exact seat number, attests to the life-changing nature of what he saw that night. “They were utterly inspiring… they’d made a conscious decision to invent a new European rock ’n’ roll music…”For Kraftwerk themselves, this was still something of a transitionary period, propelled away from their early improvisatory, avant-garde incarnation by the sudden blockbuster success of the 1974 “Autobahn” single, yet only just at the very beginnings of a decade during which their magnificent output would come to rival that of The Beatles or David Bowie. With this tour, as with The Sex Pistols’ show the following year in Manchester, the paradigm had changed decisively, even if scarcely a handful were actually there at the time to witness it.3

*

Some forty-two years on, posterity has been rather kinder to Kraftwerk than it has to Mr Ging – their status in the musical firmament assured, their already-towering legend growing in increments with each passing year. A passable analogy might be with Stanley Kubrick: a catalogue compact in scope, yet each entry a complete and peerless redefinition of the medium; a lore in which tales of obsessional attention to detail seem only to magnify the effect of the creative output yet further; a fanatical fanbase which replicates with each new generation.My own introduction to Kraftwerk came via that tried and trusted staple of pre-internet music transmission: the older brother. My brother Geoff had bought the “Autobahn” single in the mid-70s, and aged seven or eight, I had sat on the chair in his bedroom one Sunday morning, listening to it through headphones (in those long ago pre-earbud days, headphones were reserved for “serious music” only…) Submerged beneath the enormous luxuriously-padded earpieces, way too big for my childish head, I had immersed myself completely in its unbelievably futuristic sound-scape: the propulsive beat, the Doppler effect simulation of passing cars, the mysterious and under-played German lyrics. The middle section, dominated by an insistent electronic pulse and a sound collage of German cars roaring past at enormous speeds on the autobahn – even for an eight-year-old, a noticeable contrast to my father’s untrustworthy Austin Princess which would practically disintegrate over speeds of 40mph on the A40 into Oxford – was undoubtedly the most incredible and fascinating thing that I had ever heard. I can still hear my mother shouting up the stairs, trying vainly to call me down to Sunday lunch.

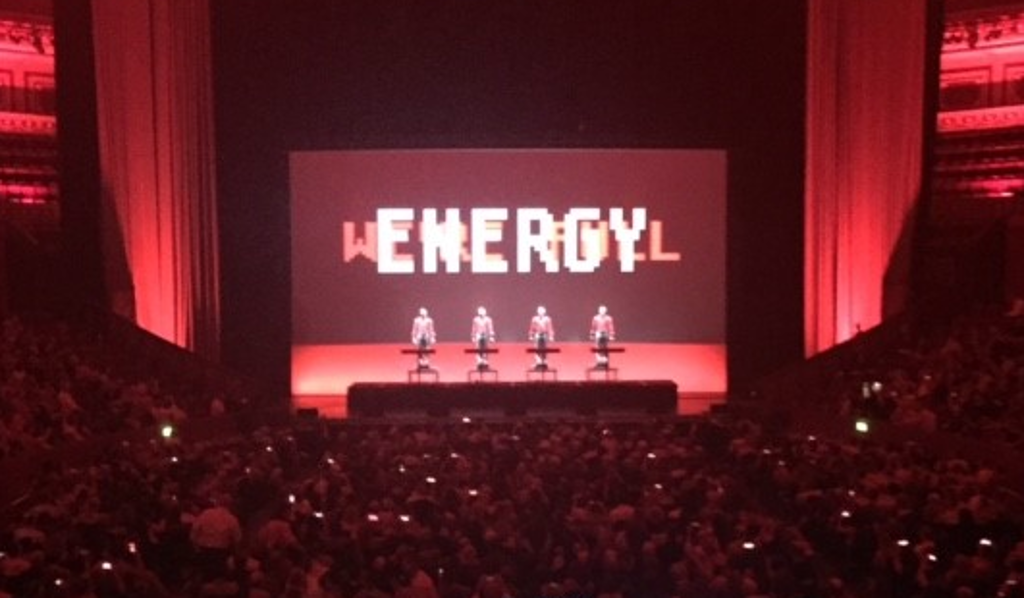

Decades later, I am sitting in the Royal Albert Hall with my own son Raul, now thirteen, and here for his first ever gig. Some years ago, when driving down that same A40, I had The Mix playing in the car (where else) and looking back in the rear-view mirror, I noticed his head bobbing along in time to the music. That was, for him, the beginning of his first serious musical love, and tonight I feel absolutely privileged to be able to share this experience with him.The current tour, the band’s most extensive of the UK since the early Eighties, brings their 3D show (premiered in 2011), across the green and pleasant lands of happy Albion. Clutching the small paper sleeve containing our 3D glasses, we take our seats early, and I feel as though I, too, am thirteen, so giddy with excitement am I. This is Raul’s first time at the RAH, and the scale of the plush red Victorian grandeur, so full of pomp and circumstance, seems stunningly memorable in its own right. As the crowds filter slowly in (security is tighter tonight than the vault at the Bank of England, with extensive bag checks and photo-ID the order of the day), we soak up the atmosphere, egging each other on in enthusiasm, and constantly checking the enormous muslin screen that encloses the stage like a silk cocoon.

Suddenly, the cocoon is illuminated with the red rectangular Kraftwerk cartouche, and whilst the four animated figures within it dance and play gently at their musical work stations, an ambient wash of pings, clicks and sub-bass swells slowly up, rolling around the circular auditorium like a Mexican Wave. This is it. We’re almost there.

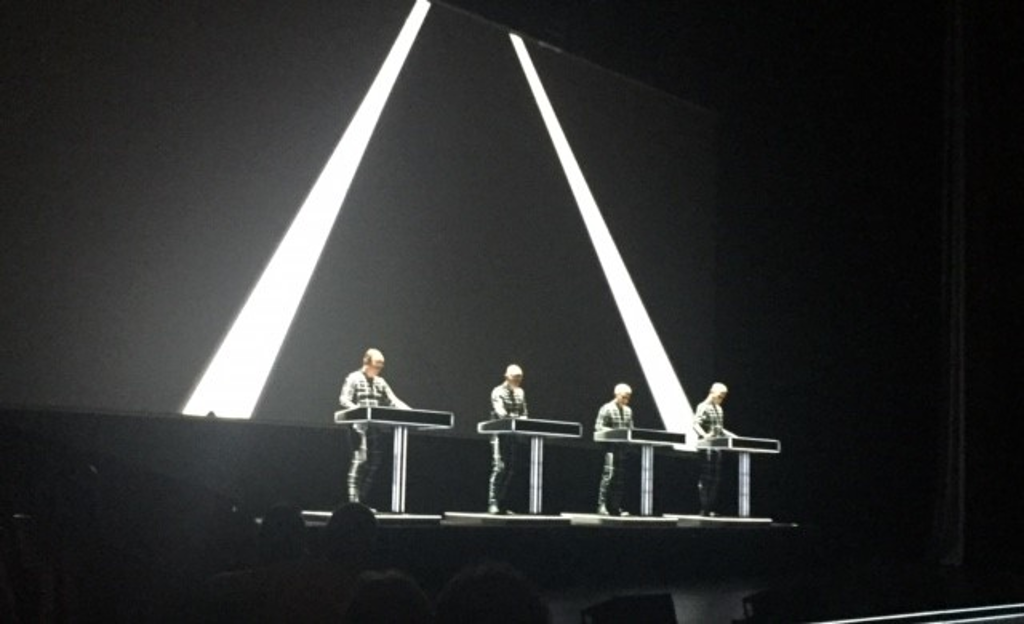

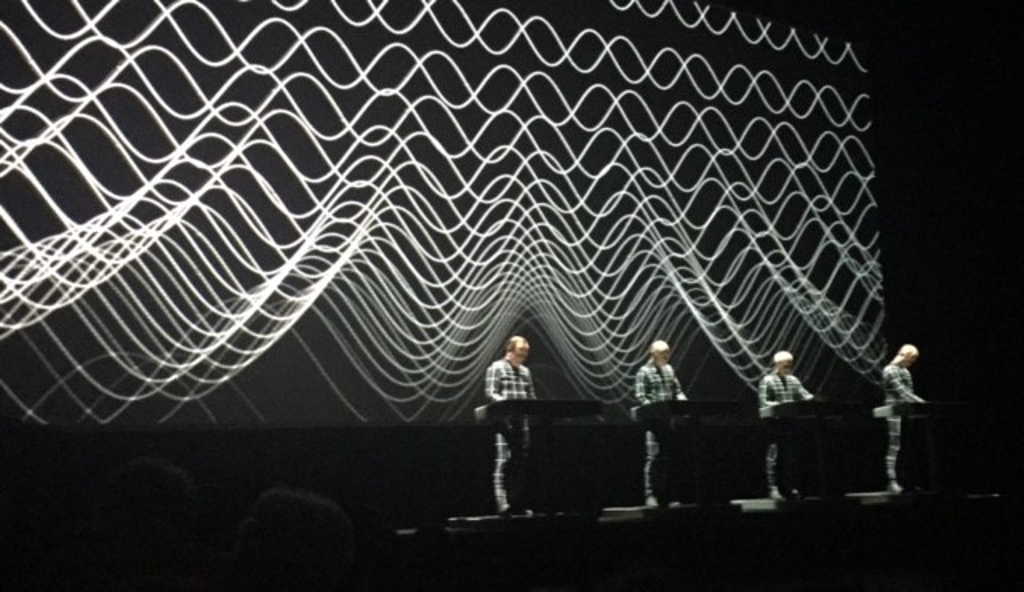

To deafening applause, whistling and calling, the cocoon rises majestically, revealing only an inky and impenetrable blackness. Swiftly, though, this is punctured by Kraftwerk’s signature vocoder vocals – “Ein, Zwei, Drei, Vier, Funf, Sechs, Seben, Acht” – and the klanging beat to “Numbers” bursts out of nowhere to shake the foundation of the hall. The linear-four music work station formation suddenly illuminates a glowing, Unix green, and there they are in their UV-reflective Tron suits. We’re off. Enormous, illuminated digits fly through the air towards us, whilst others roll across the screen like ocean tides, a choir of polyglot, digital voices guiding us through the elements of base ten. Then, with four simple notes, we move into “Computer World”, the hall’s collective feet already tapping away ten to the dozen, and an audible gasp sounding as a gigantic Hazeltine 1500 computer terminal materialises and seems to hover in the air above the band. Hollywood had a tortuous time in the past decade trying yet another attempt to interest the movie-going public in the awkward delights of 3D, only to find their hopes dashed once more on the rocks of public agnosticism.4 This, however, is what it was made for. Where Dreamworks foundered, Kraftwerk triumph.Even saturated with computer technology as we are, this feels utterly fresh. “Communication, time, medicine, entertainment”, a description of the connected present, written decades ago, by a band that saw the shape of things to come. Mark Zuckerberg may now be closing in on his dream of realising the world’s first trillion dollar company, but it is Kraftwerk’s vision of the of world that he is doing it within. What a shame that Acorn, Chris Curry, Clive Sinclair et al didn’t have the same longevity.5 A new dawn fades.

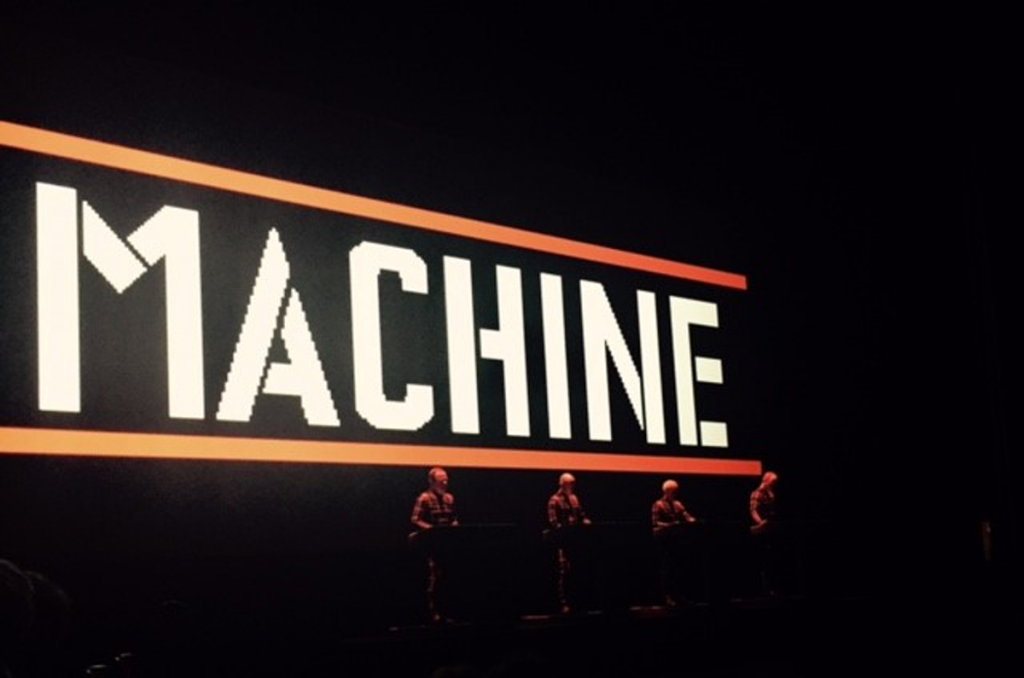

The setlist then weaves its way through all the big numbers from the Computer World album, “Home Computer”, “It’s More Fun to Compute”, “Computer Love”, before alighting on those of its predecessor. From numbers and printed circuit boards, the graphics shift direction into the arresting El Lissitzky-derived red, blacks and blocks of The Man Machine. The synchronisation between music and graphics is utterly spectacular, there is almost too much sensory information pouring into the brain to process properly. Yet in the clinging on for dear life, the exhilaration is tangible. I look over at Raul, who has not spoken, moved or hardly even breathed. He is absolutely rapt in the moment. “The Man Machine”, “Spacelab”, “Neon Lights” and “The Model” follow with the graphics going into overdrive. During “Spacelab” we find ourselves gently orbiting the Earth, the view akin to that of Dr Heywood Floyd en route to Clavius Base in 2001: A Space Odyssey. The whole Albert Hall seems to have gone into interstellar overdrive. As the proto-techno beats ebb and flow, a classic Day the Earth Stood Still flying saucer appears out of deep space, flying low over the Thames, past the Houses of Parliament (which draw a resounding boo) and landing gently in front of the Royal Albert Hall (which, conversely, draws a resounding cheer).When a map of the UK appears, with the RAH depicted by a familiar GPS inverted-teardrop tag, it is remarkable how iconography that is still considered modern and cutting-edge fits with such frictionless ease into that of Kraftwerk. One could almost imagine that they had foreseen or invented that too. For Germans of Ralf and Florian’s generation (born in 1946 and 1947 respectively), it is perhaps no surprise that looking back into the past for inspiration was far too painful, and it has become something of a truism that they, instead, had to look forward into the future. This temporal necessity, therefore, widened their hive mind to the possibilities and opportunities of that which lay ahead.

I can’t help feeling, however, that does them something of a disservice by way of the Hindsight Bias. Plenty of people had attempted amateur (not to mention professional) futurology, a Vision Thing™, and all manner of other efforts to peer clairvoyantly into the haze of the future. And a right pig’s ear they mostly made of it too. What is so impressive about Kraftwerk’s canon, catalogue, legacy, mythology, call it what you will, is how right they were, how realistic they vision was, and how it unfurled almost unnoticed around us, not in terms of Millennium Falcon hyperspace travel, but in the quotidian details of everyday life.6 There was nothing inevitable about that; they were just right.

The sound of a vehicle’s starter motor elicits an enormous cheer, and instantly I am eight years old again, utterly awe-struck, listening through my brother’s headphones to the sounds of German automotive travel. I brace myself for the Sehnsucht pleasure overload that comes when the electronic pulsing begins during the middle section. A modernised “Airwaves” is a truly unexpected treat, its lilting melody hanging in the air whilst the weaving visualisations on screen exert a hypnotic pull like Kah the Snake on the defenceless Mowgli.

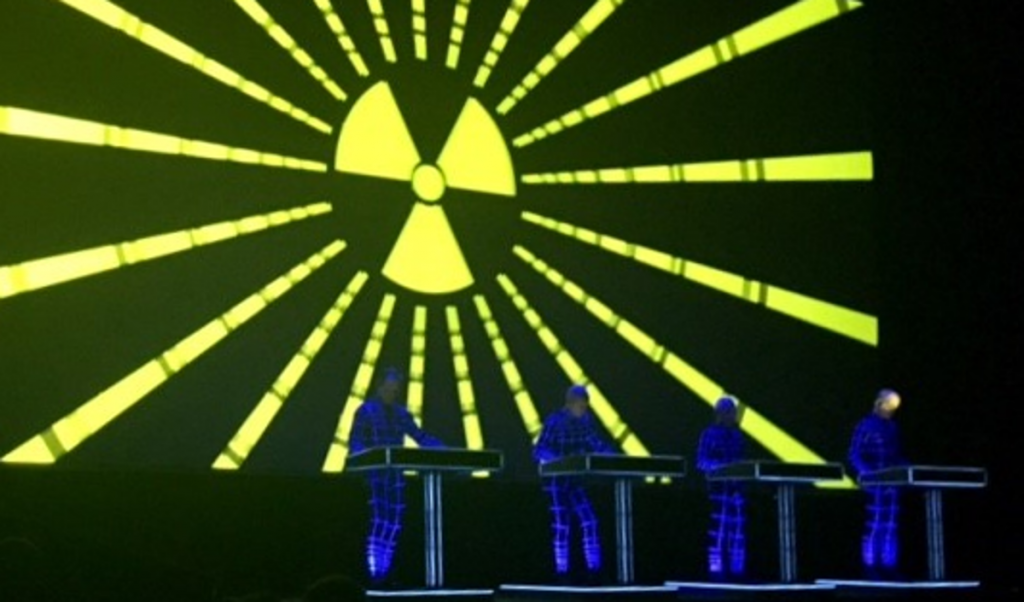

For an instant, the screen becomes completely dark, and then a small thin white circle appears, containing within it the date ‘1975’. Back to that transitional year, the uralte Zeit of the band we know today. “Geiger Counter” strikes up, and then afterwards Raul’s favourite, and probably the high point of the entire set, “Radio-Activity”. It is awesomely loud, crystal clear, and, unexpectedly, sung in Japanese during the first verse. The beat hits you foursquare in the chest, and on-screen, the 29-year old Ralf Hütter is singing above his 71-year old self in the original studio film footage from the mid-70s. The sight is actually quite affecting, in the same way as seeing Johnny Cash both old and young in the video for “Hurt”. The downside to the future is that it brings one, inevitably, closer to one’s own mortality. And with the subtle substitution of “Fukushima” for “Hiroshima”, the commentary of the song is as chillingly relevant as ever.

Then from station to station, we’re back to Düsseldorf City, as “Trans European Express” closes the proceedings, its propulsive rhythms, legendary electro riff and diagonal North-by-Northwest style visuals returning us to the Westphalian source. When the cocoon descends once more, Raul and I look at each other in astonishment, the first time in almost two hours that he has actually moved. Taking off my 3D glasses to rub my eyes momentarily, I am struck by how exhausted I am, the enormous cognitive load taking every ounce of energy and concentration to keep up with.

The audience are, by this point, going predictably nuts, and I ask Raul, “What haven’t we had yet?” He looks thoughtful for a moment and then says simply, “Robots”.Up comes the cocoon once more, and sure enough, standing there cheerful and inert in their red shirts and black ties, are indeed The Robots. The familiar Russian refrain rings out – “Я твой слуга, Я твой работник”8 – and the loveable automatons lead us through the closest we come to sing-a-long during the evening, their giant graphic counterparts towering overhead as all of them dance haltingly in two dimensions and in three.

Even here, Kraftwerk’s visionary take on AI is interestingly double-edged, the lyrics containing, as they do, ambiguous lines such as “We are programmed just to do, anything you want us to.” Currently, technologists are busy priming the developed West for a fresh wave of automation as next generation robotic labour is being readied for deployment in sectors as varied as teaching, construction, warfare, health, social care, and, perhaps inevitably, sex. The moral maze of using robots for sex is far from being navigated satisfactorily, with many pointing out the danger that robots specifically designed for eliciting human emotions and feelings could lead to detrimental emotional dependency or even outright harm.Would an online robotic partner harvest and transmit big data about their human “partner” during the run-up to climax? For anyone who thinks algorithms are intrusive now, wait until you receive an advert targeted to you through your last orgasm. Robot sexual partners and caregivers are political topics, not simply technological ones. Despite our fondness for Ralf’s circuit-driven doppelganger, I can’t help feeling that Kraftwerk thought this angle through long, long ago.

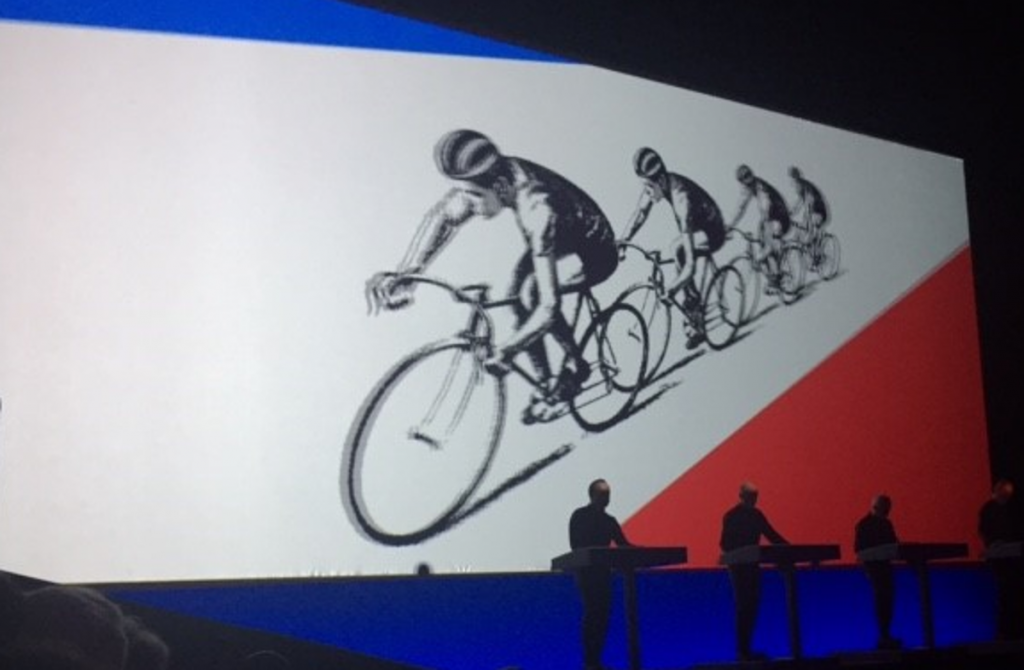

We return to two wheels for a smooth, sleek version of “Aéro Dynamik” accompanied by a filmic masterclass in the use of the echelon – a tactical drafting formation in which cyclists arrange themselves diagonally to keep a team leader sheltered from the effects of a strong crosswind – before the set finally concludes with the band’s usual outro, a medley of “Boing Boom Tschak”, “Techno Pop” and “Music Non Stop”. “Boing Boom Tschak” in particular is such a potent earworm that days later I am still blurting the phrase out spontaneously at inappropriate moments.

And so, for the final time, the cocoon comes down and house lights slowly up. Raul and I look at each other in wonder, elated and exhausted.

*

Instead, by working on the flawless digital reproduction of their sound, by refreshing the material periodically with inclusions, amendments and new arrangements, and by taking Kling Klang Music Films to an ever more breath-taking level, Ralf Hütter has instead widened the definition of “ground-breaking” and in the live arena (re)created Kraftwerk as the kind of Gesamtkunstwerk that they always threatened to be. The band’s 3D Catalogue, indeed, was premièred four years ago at Düsseldorf’s Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westphalen art collection.

Is it interesting to speculate on how long this movable masterpiece will, or indeed can, continue? As the first encore tonight attests, when the robots come out to perform, it is no less Kraftwerk when no wet-ware homo sapiens are present on stage. Hütter is on record as saying that “The master plan is [to continue playing] until I fall off the stage”, but unlike almost every other band in music history, it is actually possible to envisage Kraftwerk, long having divested themselves of human members and now comprised entire of synthetic performers, coming out to play a concert in 2117. Perhaps one day Hütter’s crowning achievement will be to replace himself completely.Music non-stop.

-Words: David Solomons-

-Pictures: Tony Collins and David Solomons-

1 The less forgiving John Lennon, typically, took a more combative stance: “I wouldn’t have turned us down on that. I think it sounded OK. […] I think Decca expected us to be all polished; we were just doing a demo. They should have seen our potential.”

2 To be fair to him, at least Mr Ging was putting forward a reasoned argument, however mistaken hindsight might show it to be. Elsewhere, the music press seemingly felt free to indulge in the kind of revolting cliché that would have made Basil Fawlty blanche. Reviewing Radio-Activity in the NME in an article entitled “This is what your fathers fought to save you from…”, Miles stated that the “electronic melodies flowed as slowly as a piece of garbage floating down the polluted Rhine”, whilst Ben Edmonds called the band’s sounds a “fascist drone” in a live Bowie review at the start of 1976.

3 Ironically, many unintentionally and unknowingly did catch a glimpse of it, as the band made their debut UK television appearance on that stalwart of BBC-budget-futurism, Tomorrow’s World. In an edition that also featured a segment about pig pedicure, a clip of the band performing in the studio was accompanied by the suave, urbane tones of presenter Derek Cooper informing the nation that “The sounds are created in their studio in Düsseldorf, then reprogrammed and then recreated onstage with the minimum of fuss.”

4 3D television was an even more unwelcome innovation, and both Samsung and LG administered a mercy killing to their wounded hopes this year, discontinuing production in January.

5 For younger readers, get online and check out the 2009 BBC docudrama Micro Men, which relates the initially thrilling, yet ultimately heart-breaking, story of a time when the UK was at the global forefront of the Computer Welt revolution. Its final image lingers long in the memory.

6 We’ll gloss over the notorious “drum cage”, soon abandoned on the 1976 tour. That said, eighteen years later, Todd Rundgren would be seen using a concept not entirely dissimilar as part of his TR-I live extravaganza.

7 Appropriately enough, le Grand Départ this year will take place in Düsseldorf.

8 “Ya tvoy sluga, Ya tvoy rabotnik / I’m your servant, I’m your worker”.