Warning: much tl;dr within. Minimal squee. Tread ye carefully.

Warning: much tl;dr within. Minimal squee. Tread ye carefully.

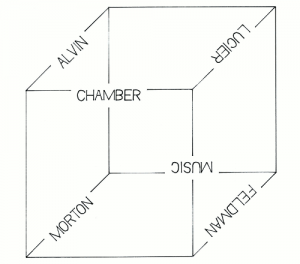

Initial thoughts on Anthony Burr and Charles Curtis‘s Chamber Music CD were something like: why would you put those two together? It’s an odd pairing. People really fall in love with Morton Feldman. He makes, at turns, utterly inscrutable, glacial, cold, dark, wrecked music that’s not so much impenetrable as it is a funeral for tonality. But note ye well, tonality is entirely key to his music.

Alvin Lucier… is not so tonal. What he is I’ll get onto, but I don’t think of him in anything like the same category as Feldman. He’s obviously known best for I Am Sitting In A Room, but there’s a fair amount of consistency across what I know of his oeuvre — often fairly static, often obviating acoustic material and properties. He often uses beating effects. What he’s academically known for is being an early-on sound artist. Back-of-a-fag-packet distinctions between the music and sound art might talk about “music” being a relatively homogenised set of sound organisations and “sound art” being less interested in concepts like tonality or rhythm and more interested in observing acoustic phenomena.

Right, so why are Lucier and Feldman so different? To my mind it’s a question of the various modes of regulation. Lucier frequently establishes a meditative tempo — a repetitive event (rather than something that’s contained within notions like bars or phrases) and often a process. There’s a nice illustration of that here:

Just to explain that a bit more — if you know I Am Sitting In A Room, you know that it’s the same speech; you know what’s coming. Each repetition ekes a little more decay but, critically, it happens in a time frame longer than phrasal (musical) time that is, never the less, regular, predictable, and therefore meditative. Meditative in the sense that breath is regulatory.

Feldman does not do this. Feldman, I think I’m right in saying, never sticks to the same rhythm in his works. While it has qualities of being (often) sedate and quiet, it is excruciatingly variegated rhythmically. I don’t want to get all comparing apples with oranges, and this isn’t necessarily indicative of Feldman’s work in general, but have a look at this: If you can’t read music at all, it shows three parts; each changes time signature on each bar; none of them are playing in the same time signature. But moreover, there’s a relatively limited amount of harmonic content — it dotes on sonorities and open chords, but there’s infrequent (direct) repetition. Feldman is kind of adjunct to minimalism, in that there’s a minimal of tonal content, but he’s very different from minimalism (if it could be considered a hegemonic genre) in that he attacks lots of non-traditional axes in music — rather than harmonic development in a baroque or classical sense, harmonic development is often felt by indirect effects of sonorities and shifting rhythms.There’s a quote from Lucier in the notes for this release that apparently qualifies the conjunction of the two composers: “For Feldman, dynamics serve an acoustical function. When he mitigates a piano attack he reduces that spike of noise that’s at the onset of every piano sound leaving only the sinusoidal pure after-sound. It’s as if he invented electronic music with the piano”. This is entirely germane. Feldman is such a delicate composer for the piano and is very careful to consider attack, and draws so much colour and (yes) beating effects from exquisitely careful note preparation. Another vision of this axis (very hot in US avant-garde circles) looks like John Cage‘s prepared piano. Fast forward a (musical) generation or two and you get the first few minutes of this — lots of very obviated attack, but also lots of obviating physical effects:

Which brings me to this collection. I can see why there’s the desire to put the pieces together. Ostensibly there’s similar instrumentation, and ostensibly there’s similar effects: “Trio For Clarinet, Cello And Tuba” (Lucier) is not so far from “Three Clarinets Cello And Piano” (Feldman). Both have this masking or otherwise effacing of attack (which the clarinet lends itself to brilliantly). The tuba can produce some gorgeous and pure sonorities next to a clarinet. But here’s the rub: the thing is is that Feldman’s music is very musical. He’s unafraid to switch gear, dropping a peculiar dissonance, doting on a note for a bit, changing rhythm drastically. Pathologically quiet.

What Feldman produces in part is an exposition of sonorities across different instruments, but the critical thing is that these are not so much by-products as they are colour, variegation. Feldman’s music so often feels nominal, slow and regular, but he’ll forever move the music somewhere else; a new sonority, a sudden dropping to near-silence, an extra note to the phrase… but it’s never static, never meditative, never regulated to the point where the listener relaxes.Lucier, on these pieces, is almost entirely the opposite — it is entirely relaxing, regulated. You let it wash over you, you observe acoustic phenomena in the crossing of notes and beating of sonorities, but it’s fundamentally never dramatic music — if, in fact, you’d describe it as music at all (that isn’t a dig, but merely an abstention as to whether sound-art is or isn’t music). But the issue then is that Feldman’s music is so awkward and variegated, moves in such a peculiar way, the Lucier’s pieces seem like a lesser version.

This isn’t a drubbing. But I guess the thing I’m worried about is that this doesn’t quite put either composer in the best light.

*

Anyway, some actual detail on the pieces: Feldman’s are from his earlier phase, in the late 1960s — I haven’t seen any scores, but I imagine they’re from a time when he was making graphic and aleatoric pieces – partly-composed pieces with open parts. He’s using (I’m inferring) an amount of dynamic control — everything quiet, attacks to a minimum, plenty of sonorities arising — but also the rhythmic content is if not irregular, then deliberately blurry by dint of aleatoric method. Lucier, meanwhile, is in a similar instrumental realm, but very repetitive – often doting on an almost non-existent amount of harmonic and rhythmic development which obviate sonorous and timbral relationships. Opener “August Moon” (f’rinstance) does a nice job of dwelling on the differences between pitched instruments and those capable of glissandi; “Step Slide And Sustain” possibly uses odd, just slightly-off parallel notes on the piano (or gives that effect by using the same, ever so slightly tinted material repetitiously).What is a shame is that Lucier is less well-known, and under-recorded (especially later works). But also it’s just such an unfortunate pairing. It’s still a worthwhile record, especially for those unfamiliar with either composer, and I can see that there’s a legion of discovery for someone who hasn’t listened to loads of both (as I have), so it’s probably something I’d give to an avant-curious youngling. But where would I be without bleating on endlessly well past the point anyone was still reading?

*

So I’ve rather more than shot my bolt with the previous record, so let’s keep this succinct: Orpheus Variations is Lucier doting on a particular phrase from Stravinsky. As usual with Lucier, there’s a world of sonority and discovery in just a few notes; but again, I can’t help but feel that I want to be in the room it’s happening in. All of the timbres are properly wrung out of the incredibly limited material, and this definitely is a piece which out-minimals minimalism.

It’s lush, but it’s also potentially the sort of thing that’d drive someone who’s not into repetitious exposition of timbral effect to madness. Again, can’t fault it if it’s the sort of thing that you might like.-Kev Nickells-

2 thoughts on “Anthony Burr and Charles Curtis – Chamber Music: Alvin Lucier and Morton Feldman / Alvin Lucier – Orpheus Variations”

I kinda love – and kinda hate your reviews! The ‘tread ye carefully’ type patter makes me squirm but the lucid analysis say of the Alvin Lucier/Feldman was interesting and illuminating. I loved your detour into Crippled Symmetry. Most of all I loved that you appear to hate Philip Glass if that touching adjective you apply is to believed. (Anything post 1974 by Glass is just horrid I think.) Anyway, I wanted to know more specifically about August Moon – how it was constructed and you sort of helped. Thanks. T

Many thanks. I’m definitely not a fan of Glass which is a longer comment for another time. I’m pleased you found a use for my hyperbolic dillentantism.

K