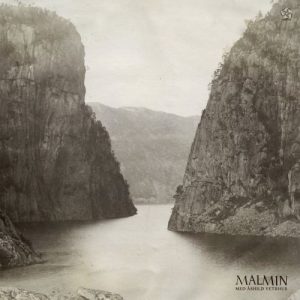

Folk duo Malmin has chosen to highlight the rugged folk music of the Rogaland region of Norway for the first release of new label Krets. Inviting singer Åshild Vetrhus to add depth and texture to the scoured bones of songs going back many years has allowed them to shed light on a tradition important to label founders Anders Hana and Olav Christer Rossebø.

Folk duo Malmin has chosen to highlight the rugged folk music of the Rogaland region of Norway for the first release of new label Krets. Inviting singer Åshild Vetrhus to add depth and texture to the scoured bones of songs going back many years has allowed them to shed light on a tradition important to label founders Anders Hana and Olav Christer Rossebø.

There is something coarse and rough about the sound of the fiddle; it scrapes and groans like a swarthy, bearded fisherman, the sort of person hewn by a harsh climate and making a tough living, while the circling motifs and relentless interaction evoke their geographical isolation. The cold water purity of Åshild’s voice suits the vision, its strong, keening tone the perfect accompaniment. The use of mouth harp adds further distance to an already removed music and the mildly evolving repetition evokes the slow changes in a glacial landscape.

They are often just on the edge of tunefulness, as if the instruments themselves are fighting back, demanding to be left alone to tell their own tale or to at least continue sounding as if nothing much has changed for in the last hundred years. The pieces are often two older forms of folk song merged together and this sense of shapeshifting as the song progresses is an intriguing one. You never quite know how a piece may evolve; a sedate processional may become a wedding dance while slow melancholy turns into a lament. It is the purity of vision that impresses and there are echoes of the original English folk tradition; a breakdown to basics that would even impress the likes of Ewan MacColl.The interplay between different instruments on each track changes their feel and makes the progression through the album quite a journey, with some having an internal dynamism that pushes them onto the hard-packed dancefloor, the sweeping repetition urging the dancers onwards, the lilting waltz-like movements soothing the soul. Towards the end, just voice and drone offer a doleful, plaintive tone that looks to God. With barely any accompaniment, the focus is the archaic tune, which once again echoes a stark and forbidding landscape.

You don’t really hear singing like this very often and what Malmin and Åshild are doing here is really important. Although unique, there is something universal in the desire to keep these songs alive. It would be fascinating to know how the original exponents might view these modern impressions; judging by the press release, most of them are long gone, but hopefully these recordings will still be with us in many decades time to maintain these traditions.-Mr Olivetti-