The old adage tells us that “Good things come to those that wait”. And I’m here to tell you that there’s more than a grain of truth in that particular piece of vintage folk wisdom.

The old adage tells us that “Good things come to those that wait”. And I’m here to tell you that there’s more than a grain of truth in that particular piece of vintage folk wisdom.

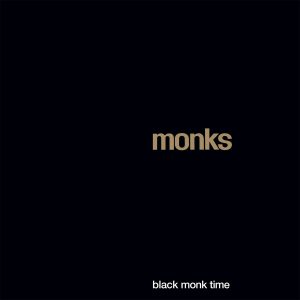

Two years ago, in August 2023, our esteemed editor dropped me a line to ask if I wanted to review a new retrospective by the Monks. Well, I ask you! Which reviewer in his or her right mind wouldn’t want to spill some ink over those freaked-out American servicemen stationed in Germany, inventing a distant, distorted hybrid of rock and roll and in doing so – it is often argued – lighting the blue touchpaper for the music that would later become known as Krautrock? Who eh? Tell me that!

Sadly, when the record arrived, the answer actually turned out to be “Me!” Not because I had gone off the idea, however, but entirely due to the fact the retrospective in question turned out to be by a completely different band. A completely different band also called The Monks. Really? Are you effing kidding me? Sigh.When resiling from the assignment, in anguish I commented: “This is a UK new wave band called The Monks, doing lowest common denominator skinny tie guitar music with a slightly mockney accent. File under Forget.” Harsh perhaps, but understandable given my crushing disappointment.

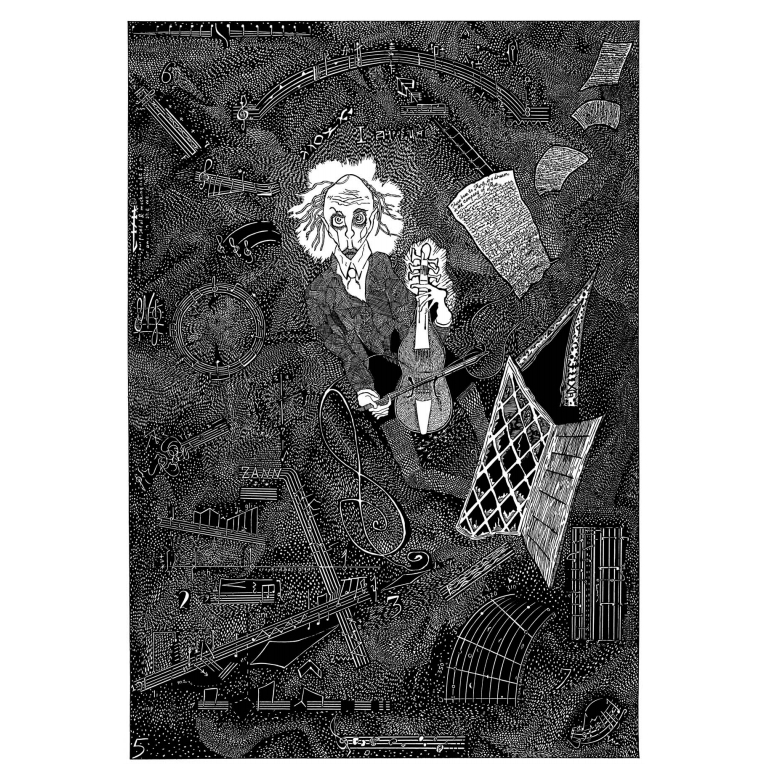

Yet flash forward only twenty-four short months and, praise be, the genuine article has at last fallen into my lap. For, as it lurches towards its sixtieth anniversary – sixtieth! – The Monks’ only album, Black Monk Time, is just being readied for reissue, and thankfully your humble scribe is at last touched by its presence (dear).And so, having listened again with fresh ears, what are we to make of this head-scratching musical oddity some six decades after its creation?

By way of a recap, or an introduction for those as yet unfamiliar with their cloistered world, The Monks comprised five American GIs who, during the height of the cold war, were serving in Gelnhausen in what was then West Germany. In their early days, The 5 Torquays, as they were then known, played fairly straight-ahead interpretations of the classic 1950s rock and roll songbook, supplemented by a few self-penned songs, performing their material to boisterous audiences of locals and fellow servicemen at military night-spots near their barracks as part of an army-sponsored PR outreach programme.

Yet from this charming if unpromising beginning did magic happen. For, whilst playing a residency at the Rio Bar in Stuttgart and experimenting with new ways to expand their sound, in a moment of delicious musical alchemy, like Lou Reed and US and Steve Marriott in the UK, the band stumbled upon the Philosopher’s Stone that was feedback and distortion. With a guitar left propped against an amplifier during a bathroom break, the band began jamming along to the howling frequencies that resulted, accidentally finding the pivot around which their new music could move. “The amplifier shall sound, and we shall be changed”. And so they were; not only their sound, but their name and their image, too. And how.

Over the course of the next year, the band evolved a unique musical style: stripped-back and heavily focussed on rhythm, powered by new equipment including the crunchy Maestro Fuzz-Tone pedal, and embellished with unusual instrumentation such as the banjo, which more than one observer has seen as being as integral to their unique style as was the jug to that of The 13th Floor Elevators.Together with this reconstituted musical approach, a new name was chosen, The Monks, and supporting this – and, let’s be honest – most startling of all, was the look to match: high medieval Catholic chic including black habits, cinctures worn as neckties (representing so it was later said “the metaphorical nooses worn by all of humanity”), and no-compromise tonsure haircuts. One wonders what the potential sartorial interpretation might have been if the band’s other name choices, Molten Lead or Heavy Shoes, had won instead?

Perhaps unsurprisingly, potential enablers Polydor Records were more than a little wary of both the band’s aggressive new musical approach and its rather merkwürdig stylistic choices, particularly given the stirrings of a religious backlash against what was perceived as being a disrespectful appropriation of Catholic religious vestment. Nevertheless, after proving their worth through a serious of shows in Hamburg, Polydor loosened the purse strings enough to allow the Monks to enter their studio in Cologne in late 1965 and record the bulk of what would be their first, and only, album: Black Monk Time.Despite the technical limitations of the studio, coupled with an exhausting schedule for the band which saw them supporting Bill Haley And The Comets by night and arriving early at the studio to work by day, producer Jimmy Bowien still managed to navigate his way through such impediments and capture their peculiar Monkish lightning in a bottle. As the band’s vocalist and guitarist, Gary Burger, would later recall:

Our labelmates were people like Bert Kaempfert, but our producer was an absolute jewel of a man. We trusted what he was trying to do. Black Monk Time is exactly what the Monks sounded like live. No overdubbing. Very energetic, very precise and, of course, very loud.

Across a dozen tracks – with a handful being recorded later in Hamburg – as Don Gallucci would do with The Stooges five years later on Funhouse, Bowien faithfully translated the band’s pile-driving new live sound onto vinyl: the thumping repetitive groove of bass and drums, the angular guitar bursts, the percussive riffs of electric banjo and urgent stabs of organ, and the confrontational, upfront vocals.Looking back from the perspective of sixty years, one can easily over-burden the music of Black Monk Time with heavily freighted descriptors such as ‘proto punk’. There seems to be little contemporary evidence, though, that the band were trying to overthrow or react against a stale and constricting musical order (as bands like The Electric Eels or The Sex Pistols would do in the following decade). Rather, the Monks, wanting to follow a path of their own, were instead simply unsheathing their US Army-issue service knives and hacking a new path through the musical undergrowth.

… took full artistic advantage of their lucky / unlucky position as American rockers in a country that was desperate for the real thing. They wrote songs that would have been horribly mutilated by arrangers and producers had they been back in America. But there was no need for them to clean up their act, as The Beatles and others had had to do on returning home, for there were no artistic constraints in a country that liked the sound of beat music but had no idea about its lyric content.

Opening track “Monk Time”, with its frenzied pace straight out of the gate and its mad assemblage of lyrical barbs against the army, James Bond, the atomic bomb and the Vietnam War seems very much to prove Cope’s point. Grosvenor Square and Kent State were still years in the future, but already in 1965, the Monks were asking “Why do you kill all those kids over there in Vietnam?” And a line such as “We don’t like army” coming from a bunch of soldiers recently off their tours of duty carried a certain gravitas that made it a dangerous statement not easily dismissed by more conservative pundits. These were not Laurel Canyon do-gooder hippy types, these were GIs.After this frenetic opener, we race through a dozen succinct statements of Monkish intent, each track rarely exceeding the two-and-a- quarter minute mark: the oddball borderline-yodel and full fuzz assault of “Higgle-Dy Piggle-Dy” (like The Vogues with a Big Muff pedal), the pounding tribal stomp of “I Hate You”, the jagged psychosis of “Complication” and the hypnotic Farfisa oobie-doobie of “We Do Wie Du”.

My personal highlight is the driving “Oh, How to Do Now”m a delicious propulsive groove, uniquely in the Monks’ style, which can still keep a dancefloor moving as much as it did when the band showcased it live on popular German music show The Beat Club in 1966. Luckily, the footage of the song, along with the other tracks recorded during that appearance, can still be found online, giving us an lip-smacking glimpse of the band in their prime, and confirming Burger’s assessment of how well Bowien translated their live sound into its recorded form. One particularly delightful and perceptive below the line comment on a noted video content site exclaims at how the Monks seem like Devo a decade beforehand.

The next eighteen months saw little improvement in the band’s fortunes. Despite a lengthy tour in support of the album, the gradual dawning of a more psychedelic era and internecine disputes around moderating the band’s harsher style and including cover versions began to erode the unity of the band. Two lacklustre singles which attempted to smooth out some of the band’s rougher edges, “Cuckoo” and “Love Can Tame the Wild”, did nothing to put their career back on track. Several members even stopped dressing as Monks.

Bassist Eddie Shaw recalled that, when playing with The Jimi Hendrix Experience at the Star Palast in Kiel in May 1967: “That’s when I began to suspect we’d already passed the height of our careers and that really, we weren’t going anywhere”. A mere four months later, Shaw was proved right, and ironically, on the eve of appearances in Vietnam, the Monks disbanded quietly.

Thankfully, though, as with the work of so many early pioneers, time proved kinder to the Monks than ever did their contemporary milieu. Championed by later luminaries such as Mark E Smith, Jello Biafra, Iggy Pop, Jon Spencer, Jack White and the aforementioned Henry Rollins, Black Monk Time gradually emerged from its gothic German crypt to win over hearts and minds with its no-nonsense purity and uncompromising sense of identity.

Genesis P Orridge was quoted as saying the Monks were the missing link between beat music and The Velvet Underground. Alec Empire has said that he believes that if a line were drawn backwards from Einstürzende Neubauten in the 1980s, through the motorik Krautrock of the late 1960s and ’70s, it would ultimately extend back to the Monks. Like the pebble dropped into the quiet pond, the ripples of Black Monk Time extended out a long way.Now I’m not suggesting that you nip down to the barber’s and ask for the full tonsure but, to quote the inspirational opening of the album, “You’re a Monk, I’m a Monk, we’re all Monks”. Get this one on the turntable and crank it all the way up. It’s Monk Time.

-David Solomons-