In 1908, GK Chesterton, known by many as the “prince of paradox”, expounded his theory of change using the example of a white post. Some people, he maintained, had the idea that:

In 1908, GK Chesterton, known by many as the “prince of paradox”, expounded his theory of change using the example of a white post. Some people, he maintained, had the idea that:

…if you leave things alone you leave them as they are. But you do not. If you leave a thing alone you leave it to a torrent of change. If you leave a white post alone it will soon be a black post. If you particularly want it to be white you must be always painting it again; that is, you must be always having a revolution. Briefly, if you want the old white post you must have a new white post. But this which is true even of inanimate things is in a quite special and terrible sense true of all human things. An almost unnatural vigilance is really required of the citizen because of the horrible rapidity with which human institutions grow old.

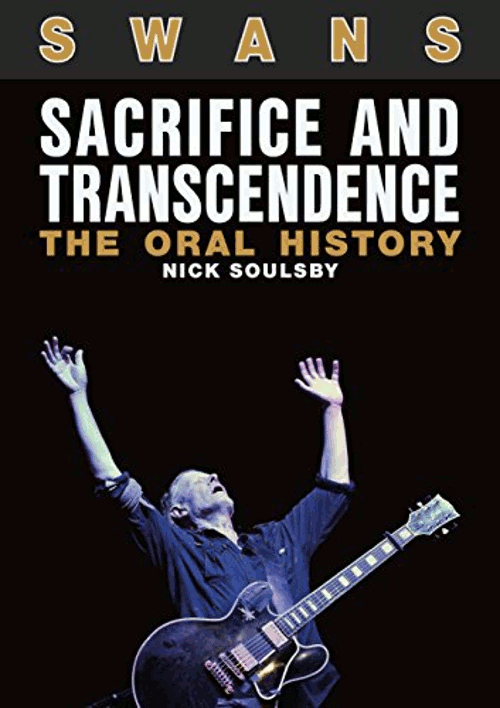

There can surely be few better encapsulations of Michael Gira’s near forty-year odyssey with Swans than this. The white post of his uncompromising musical and artistic vision has never changed, driving him therefore to repaint it constantly, decade after decade, always having a revolution, in order to stay true to it. More than almost any other musician of his generation, Gira has demonstrated Chesterton’s “almost unnatural vigilance” in preventing the institution of Swans from growing old.

Carrying out this colossal endeavour since the band’s formation in 1982 has burned out more than a few people along the way – no-one more than Gira himself – and the economic and personal rewards have many times proved utterly pitiable. Yet there has been, for me at least, an incontestable proof of the success of Gira’s endeavour; Swans have done their best work this decade (since their return from a thirteen-year hiatus in 2010). The artists and bands whose work four decades into their career is sharper, more incisive and characterised by even more intense sunlight and ever-deeper and more complex shadows than that of their early years can probably be counted on the fingers of one hand. Swans are one of those very few.And, as if we need reminding, it is not as though they were starting from a low benchmark. For many who encountered Swan’s work during the 1980s it felt like a Copernican revolution, a shift of musical understanding to levels of intensity which, even in the aftermath of punk and the myriad strange children it begat, few had realised were possible. Even before that decade had ended, a growing corpus of Swanlore had already begun to accrete around the band, whispered in reverent tones by questing souls seeking refuge from the indescribable musical horror of the contemporary mainstream: the unrivalled power of their sound, the volume at which people would sometimes lose consciousness, the concert venues being compelled to reinforce their load-bearing walls in order to survive the event, the deliberately hermetically-sealed and uncooled gigs that became hotter and more concentrated than a Chumash sweat lodge.

As Joe Strummer sang in “London Calling”, “Yes, I was there, too. And you know what they said? Well, some of it was true.” I well remember arriving ridiculously early one night at the Harlesden Mean Fiddler to see them. Though it meant we secured a coveted front row spot, the disbenefit was an ensuing wait that saw us having to stand for an excruciatingly-extended period, which could be dispiritingly measured visually via the (soundless) films being projected on the screen that stood at the rear of the stage: the whole of David Lynch’s Dune, and then half of his Eraserhead. Jostled and crushed against the edge of the stage, the temperature creeping inexorably upwards, it was a taxing and uncomfortable ordeal, breaking down all resistance before even a note had been played.Yet it was worth it for the set that followed, all the discomfort melting away before an astonishing display of might and exactness, one which felt much more akin to a religio-spiritual experience, a desertion of the ego to reach something further beyond, than it did to a rock concert, even of the most outré kind. Towards the end, drenched in sweat and far away in inner space, whilst they played the final song, “New Mind”, I felt as though I had finally escaped the crushing embrace of a gigantic hand that had been wrapped around me, squeezing me until my organs had almost displaced, and was now somewhere entirely calm and still and distant. I had broken through at last to the mythical eye at the centre of the storm. And such an experience was neither infrequent, countless others reported similar feelings of the numinous and the exultant, nor accidental, being the directed and intentional object of Swans’ extraordinarily potent performances.

Nick Soulsby is another who obviously experienced this state of grace through the music of Swans, and in his excellent new book, Sacrifice And Transcendence: The Oral History, he attempts to explain, both musically and logistically, how it came about and how it managed thereafter – against seemingly intractable odds – to evolve and even prosper across the hard yards that followed.Taking the form of snippets of interview and commentary arranged into commonsensical chronological portions, the dramatis personae is impressive and intriguing: the expansive retinue of former band members, NYC counter-cultural stalwarts (Lydia Lunch, Jim Thirlwell), associated facilitators and industry supporters, quirky bit-players (Monika Döring, the “punk granny”), occasional familiar faces (Neubauten luminary Alexander Hacke, international platinum unit-shifter Madonnai), it really goes on and on.

One of the most refreshing aspects of this approach is that it manages the not inconsiderable feat of avoiding total Gira-centricity. Though Gira himself may often have longed for Swans to be a “band of brothers” in the mould of say, Can, (and this comes through clearly in several passages), it eventually became apparent, even to Gira himself, that he and Swans were one, indivisible. This ineluctable fact could easily have come to dominate the narrative of the book. Yet Soulsby’s technique avoids this almost-irresistible gravitational pull, and instead provides ample space for the contribution of others – whose input into the band’s music and survival was crucial, if often overlooked – to shine throughii. And it is, most certainly, a stronger book for it since, rather than having to rely solely on Gira’s perspective, or indeed Soulsby’s own, one is left to triangulate a standpoint, noting both the contradictions between the views when they occur, and the overwhelming points of consensus. That is not to say that Soulsby has not editorialised (one cannot write without doing so), but his approach is a text that is light and airy, yet possessed of a genuine narrative force.

From Gira’s turbulent (and often terrifying) childhood and adolescence, through the LA punk sceneiii to the creative ferment of late 1970s New York, and on to the life of a working band in America and Europe, one can see not only changes in Swans, but also in the wider world in which they operated. Their short jaunts behind the Iron Curtain, for example, are particularly fascinating.Seeing the combination, year after year, of the preternatural level of intensity that the band were expected to reach, together with rigours of life on the road on a marginal (and sometimes non-existent) budget, it is no wonder that the instrumental roles in the Swans became something of a revolving door. Few, if any, could keep the necessary pace up for any duration. Eventually, exhaustion, or irritation, or musical differences, or just simple economics, would intervene and cause a Swan to peel off from the formation. One can sense, almost tangibly, Gira’s feeling towards this, a simmering blend of anger and sadness, but as much as he sometimes screamed, bullied or cajoled others to produce a performance of sufficient excellence, or to prolong their time with the band, he was even harder on himself. Nature gifted him a robust physique (his early years in construction attest to that), but one nevertheless boggles at how he himself managed to sustain the effort. Others came and went, but he remained its unmoving centre. It was an epic feat of endurance.

The truth that emerges subsequently over the course of the book’s 300 or so pagesiv – and, in all candour, it is hardly a surprising one – is that Gira has always been a driven individual: desperate to realise successfully and meaningfully his artistic vision, desperate to give his audiences something truly consequential and, at the risk of sinking lazily into the psychotherapeutic armchair, desperate to avoid the penury and personal annihilation that he often witnessed in adults during his childhood.In retrospect, propelled by such a weighty burden, it was to be expected that it would bring him into conflict, more or less frequently, with other members of the band, the music industry and the world around him. They simply could not keep up with his vision, often even he himself could barely do so, and so verbal confrontation, frayed tempers and the occasional ill-tempered relationship rupture became the order of the day. Interestingly, though, given that, the bulk of the commentary of the participants is not attacking or critical of him. Vexed perhaps, rueful from time to time, bemused, irritated or exasperated, yet every interviewee seems to know both that Gira drove himself even harder, and that such personal foibles as they had to contend with were mostly fired by his unrelenting desire to realise an artistic and musical vision which they all, to a man and woman, knew to be something special and worthwhile. Gira as band leader archetype, in the fashion of James Brown, or perhaps Mark E Smithv, is a possible comparator, yet it seems nowhere near satisfactory somehow. Perhaps more fitting is that of Werner Herzog or Stanley Kubrick, visionary cinematic mavericks both, whose unyielding pursuit of the extraordinary would sometimes alienate those around them, but the results of which few would ever honestly criticise.

Kubrick’s unusual technique of actor management, for example, came particularly to the fore during the making of The Shining, in which he subjected Shelley Duvall, his lead actress, to treatment which she later characterized as “excruciating, almost unbearable.” He harangued her for minor mistakes and forced her to endure an abnormally large number of takes. The scene where she walks backward up the stairs, sobbing and swinging a bat ineffectually at Jack Nicholson, was shot at least thirty-five times. Some reports put it nearer to 130. Despite her personal discomfort, the result was that Duvall looked stressed, tired, and haggard, the very performance Kubrick had wanted. Hearing some of the former member of Swans talk about full-force emotional beat-downs from Gira during rehearsals, or even gigs themselves, one cannot help but conclude that he was taking a similar approach.At one point, Jarboe relates that in the quest to build up a choral background of voices, rather than copy, cut and paste a performance multiple times, she was compelled to sing single each part through separately from beginning to end:

I remember asking [Gira], ‘What’s the point in giving so much to every single track of fifteen vocal tracks when they’re mixed together and mixed so low you can’t tell one from the other?’ And he told me, ‘Every single track has to be that much – every single one’. That’s what I took away: never be satisfied. Every nuance as much and as best as you can give.

Again, this finds echoes with The Shining’s famous scene in which Duvall finds that what she took to be Jack’s voluminous manuscript is merely page after page of the repeating phrase, “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy”vi, typed by Jack in the full throes of psychosis, demonic possession, or possibly even both. Legend relates that Kubrick insisted that every single one of the 500-odd pages be fully typed, complete with mistakes and the full gamut of typographical weirdness characteristic of manual typewriters, so that no matter where Shelley dipped into the paper, she would find convincing evidence of Jack’s descent into derangement and murder.

As someone once said, “I realised that… this was a whole new ball game, and that the word ‘reasonable’ was not in [his] lexicon”. But was it said of Kubrick, or of Giravii?That is not to say that the book is nothing but earnest discussions of artistic merit, or doom-laden mediations on power, greed, holiness, money or holy money. Far from it, the are many amusing anecdotes, observations and recollections. Life on the road with a band is a chaotic, madcap and occasionally hilarious affair, and Swans were no exception. Having a glimpse into the trials and tribulations of their quotidian existence only adds to, rather than detracts from, any reverence for the levels of precision and power they managed to bring to their live shows.

A rather depressing aspect of the book, though, is undoubtedly how little financial reward accrued to the band for their years of hard work. As a youngster, looking on in slack-jawed amazement at their musical magnificence, I took it as read that the albums and the tours were income streams sufficient to allow the band to exist reasonably comfortably as professional musicians. To read that, at the age of forty, Gira had to move in with Jarboe’s mother, with little more than the proverbial tin pot to piss in, is a dispiriting and damning indictment on the music “industry”. That Gira managed to overcome even this bleak position, and turn it into the positive of Young God Records, is an achievement every bit as inspiring as the music that he has produced.

The chapter concerning Gira’s years of devotion to Young God itself demonstrates amply both his total and selfless commitment to the acts which he signed (leveraging his own fame in order to gain exposure for those who would otherwise not have access to anything remotely similar) and the seriousness – and gratitude – with which he treats his fans. Which figure of comparable musical stature can one picture sitting down on Christmas morning to package CDs and hand-write individual messages ready for mail-out to loyal subscribers? Bloated self-indulgence, creation fatigue and sheer laziness have made many a tired musician consciously toss out any old shit in the expectation that “The fans will take it”, but despite all and any of the nadirs, setbacks and disappointments of his career, this is something that Gira has never done. The band members know it, the fans know it and, one hopes, Gira himself knows it.

Towards the very end of the book, former bassist Bill Bronson comments perceptively: “I’ve often thought ‘What if another Lower East Side New York death-metal schmuck had the same concept?’ Bands have tried, but none of them last because they’re virtually unlistenable – [Michael Gira’s] the only one who can make it work”.

As unwilling to rest on his laurels as he evidently seems to be, even Michael Gira can surely allow himself a small pat on the back for that at least.

As the great man is apparently sometimes wont to say, trust your Uncle Mike.

-David Solomons-

i A small appearance, but a truly delicious one.

ii It is particularly illuminating to hear Jarboe talking about both the development of the music, and about the life in and around the band more broadly. Having stood underneath her at the stage edge during the band’s show at the Town and Country Club in London in 1987, as an impressionable teenager I was absolutely in awe of her. After reading Soulsby’s book, as an over-fifty, I am even more so.

iii I was absolutely thrilled to find out that Gira has once auditioned as a bassist for the mighty Flipper!

iv Plus generous photo middle section.

v There are interesting parallels between The Fall and Swans, whose paths do indeed cross during the course of the book’s narrative. MES, that great Son of Salford, makes a pleasing cameo.

vi Being so attentive to every shot and its possible resonance, Kubrick decided it would detract from the impact of the scene if non-Anglophone viewers had to read the troubling phrase in subtitles instead of actually on the page. He therefore had similar insert shots made of the manuscript featuring alternative phrases typewritten in a variety of different languages. The Italian version was particularly poetic: “Il mattino ha l’oro in bocca” (“The morning has gold in its mouth”).

vii It was actually said of Kubrick by Garrett Brown, inventor of the Steadicam, who worked memorably on The Shining. But compare this to a description of Gira from Miles Seaton (of Akron/Family): “He’s willing to risk everything, to push people beyond their physical, emotional and spiritual boundaries, so long as there’s a chance he can take them to these moments they can’t achieve any other way”.

viii Bish Bosh excepted.