Nico icon, as they say. Model, actress, singer, nomad, member of The Velvet Underground, heroin addict, mother, cyclist, friend of Jim Morrison and Brian Jones: the list could potentially go on and on and still scarcely scratch the surface of this complex and contradictory woman. To paraphrase another musical geniusi, she was so strong, she was so bold, when they made her, they broke the mould.

Nico icon, as they say. Model, actress, singer, nomad, member of The Velvet Underground, heroin addict, mother, cyclist, friend of Jim Morrison and Brian Jones: the list could potentially go on and on and still scarcely scratch the surface of this complex and contradictory woman. To paraphrase another musical geniusi, she was so strong, she was so bold, when they made her, they broke the mould.

Born in Germany in 1938, like many of her generation, Nico’s young life was shaped by the trauma of the post-war world, coated in rubble dust, and shot through with fear and shame. Whatever the moral aspect of the Götterdämmerung which had enveloped Germany, to be seven years old and witnessing the horrors of the smashed and shattered city of Berlin, and the unspeakable things which happened there in the aftermath of the surrender, it is perhaps unsurprising that Nico’s life and work were both emanations from the shadows.

Having been spotted working at the Kaufhaus des Westens department store in Berlin, a long series of events then occurred which saw Nico become first a model and wistful, enigmatic face on a number of notable jazz albumsii, then an actress appearing for Frederico Fellini, whilst relocating to Paris and New York and becoming multi-lingual in the process. That would have been quite eventful enough, but is essentially just the preamble.The chain then loops wider still to encompass Brian Jones and Bob Dylan, vocal tuition and a move into singing, an early Jimmy Page-produced singleii, and, in 1967, her first really substantial contributions to music: acting as chanteuse for three tracks on the seminal masterpiece The Velvet Underground and Nico and her first full solo album, Chelsea Girl.

However, immediately after Chelsea Girl, with its relatively straight-ahead folk pop approach, Nico’s Jungian shadow rapidly began to assert itself. The precipitant for this change was Jim Morrison, who encouraged Nico to start writing her own songs, and introduced her to a range of inspirational techniques from dream diaries to ingestion of heroic quantities of peyote.With the Lizard King’s tutelage, and a battered harmonium which she bought from – depending on which source you chose to believe – either a local hippie or Leonard Cohen, Nico’s second album, 1968’s The Marble Index was a much darker, starker affair characterised by the doom-laden harmoniumiv, Nico’s newly-liberated compositional voice, and former bandmate John Cale’s modernist production and arrangements. Haunting and wounded, this was clearly not a hit parade proposition.

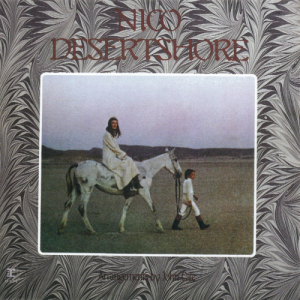

The following year, Nico performed a song called “The Falconer” for the soundtrack of a film called Le Lit De La Vierge (The Virgin’s Bed) by young French director Philippe Garrel, beginning what was to become a decade-long relationship between the two mavericks, one both romantic and professional. Their next collaboration, Garrel’s surrealist film La Cicatrice Intérieure (The Inner Scar), in which Nico and her young son Ari starred, would yield five of the songs which appeared on Nico’s third album, 1970’s magisterial Desertshore, along with its cover images.

By 1970, though, that ship of dreams was being repeatedly dashed against the rocks, leaving many shipwrecked and broken in its wake: as Danny, the likeable but fried dealer of Withnail & I so memorably puts it: “We are ninety-one days from the end of this decade and there’s gonna be a lot of refugees.” Desertshore is a poem of remembrance for those refugees.

Singing in three languages (English, French and her native German), playing her harmoniumv, and supplemented by Cale’s deftly minimal piano, this is music like a cold wind rattling through the bare branches of the winter trees. Nico’s vocals are forceful, desolate and utterly mesmerising – the ascending scales of second track “The Falconer” belie forever the accusations levelled against her by those that have only ever heard All Tomorrow’s Parties that she was a limited singer.

Ari, who at only eight years old still had a troubled life ahead of him, makes a plaintive appearance singing the minute-long “Le Petit Chevalier” in halting French, his mother audibly whispering the last line to him: “J’irai te visiter.”

Like the loose trilogy of which it forms a part alongside predecessor The Marble Index and successor The End, Desertshore is the sound of Nico trying to exorcise ghosts, a dark vortex around which swirl the bitter waters of the death and despair that seemed so close to her. Sadly, those flood waters would only continue to rise as the trilogy reached conclusion – The End features the song “You Forget To Answer”, which relates Nico’s pain when she failed to reach Jim Morrison by phone, only to find out soon after that he had died.Unsurprisingly, Desertshore was not a major critical or commercial success upon its release in 1970. It is hard to imagine who its audience might have been then, so far removed was it from what was happening at the time. Yet, as with so many marginal masterpieces recognised only in retrospect and from a distance, Desertshore – and Nico’s wider oeuvre – have grown in stature over the years.

Musicians as diverse as Michael Gira, Robert Smith, Björk and Morrissey have all cited Desertshore as a key influence, and Nico’s dark penumbra falls long across so many genres which leave the path and venture deep into the darkness of the forest. As Pete Murphy from Bauhaus once put it: “Nico was Gothic, but she was Mary Shelley to everyone else’s Hammer Horror. They both did Frankenstein, but Nico’s was real.”Nico, you are beautiful and you are alone.

-David Solomons-

i I shall say only Tilt.

ii Bill Evans’ 1962 classic “Moon Beams” for example.

iii 1965’s “I’m not sayin’”, with top session man Page producing and providing guitar.

iv Cale commented that the harmonium “was out of tune with everything. It wasn’t even in tune with itself.”

v The separation of which would cause producer Cale no end of headaches.