Medical

We should all rejoice in the fact that finally the first two Pram albums proper have been given the re-issue treatment, and what a lovely job Medical Records have made of them: coloured vinyl, recent interviews amongst the sleeve notes and a clear appreciation for the magic contained therein.

We should all rejoice in the fact that finally the first two Pram albums proper have been given the re-issue treatment, and what a lovely job Medical Records have made of them: coloured vinyl, recent interviews amongst the sleeve notes and a clear appreciation for the magic contained therein.

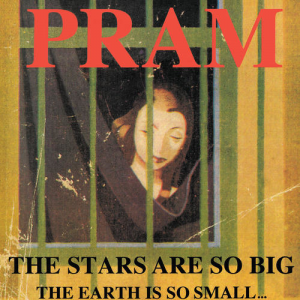

Whereas their first, self-produced release Gash revelled in a kind of darkened bedsit paranoia and lo-fi musical abandon, these two albums — 1993’s The Stars Are So Big… and 1994’s Helium — give the impression of the bedsit’s shutters being flung open, windows thrown wide and a world of musical possibilities making its way in. Much has been made of Birmingham’s multicultural musical melting pot and Pram, having been birthed in those Midlands suburbs, found everything they needed right around them, rather than lazily looking towards London for inspiration like so many other bands of that era. In fact, besides Stereolab, I can think of no other band of that time that came close to Pram’s scope and imagination; they were and still are one of the most important bands the UK has produced.

The first of the albums issued here, The Stars…, straddles the divide between the claustrophobia of Gash and the exotic fervour of Helium. One of the first bands, way ahead of their time, to embrace the recycling of exotica, you can see their love for Martin Denny and Les Baxter as much as their love of Can, outré jazz and dub. The spiky guitar and cavernous bass of opener “Loco” works well as a segue from Gash, but the wild bongo and cymbal rhythm lend it a mischievous air — from there on in, things become jauntier and a wild array of instruments cavorts through the first side. The violin sounds like a kazoo in “Radio Freak, the chimes ring in your ear like fairground monkey bells and the local dub influence comes to the fore on the tummy-rumbling “Loredo Venus”.The appropriation of esoteric instruments and children’s toys, the wonderful, half-spoken vocalisations of Rosie Cuckston and Darren Garratt’s relentlessly inventive drumming make the whole side a kaleidoscope of sound and imagery as we veer from bedroom to fairground and village hall to space museum. Side two embraces space in both senses of the word as the band let loose their inner Sun Ra and set search for the cosmos. For Pram, space is a vast and lonely place, and with the sixteen minute “In Dreams You Too Can Fly”, the use of space finds Matt Eaton’s questing trumpet and the drifting organ giving a sense of its vastness, whereas the interstellar transmissions of “The Ray” push things even further out.

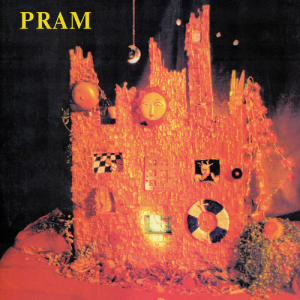

The frenetic, galloping drums of “Gravity” open Helium’s proceedings, and the overall feeling with this album is that there are more frolics and adventures to be had back here on earth. There is more light, more texture with the wheeze of the organ and the quease of the violi, the discovery of the box of delights that is the sampler lending extra layers to the songs.

The frenetic, galloping drums of “Gravity” open Helium’s proceedings, and the overall feeling with this album is that there are more frolics and adventures to be had back here on earth. There is more light, more texture with the wheeze of the organ and the quease of the violi, the discovery of the box of delights that is the sampler lending extra layers to the songs.

Once again, it is a drumming tour de force, rhythm light as air on “Dancing On A Star”, the seahorse-like bob of “Night Watch”, the stridency of the delicious “Things Left On The Pavement”. The songs almost glisten with the samples strewn across them, begging to be identified. “Windy” sounds as if somebody has recorded a tumble-drier at 16 rpm in a bird-strewn meadow, whereas “My Father The Clown”’s lurching waltz and disturbing imagery is one of the few morose moments

Stereolab ploughed a similar furrow and the like of l’augmentation and Broadcast followed, but Pram’s secret is that they are greater than the sum of their parts, all topped off by Rosie’s beguiling, delightful vocals. It is not just the timelessness of the music, but the plethora of fresh ideas, the obvious joy and artistic abandon which went into its making. The zenith of the album is possibly the fantastically rhythmic “Little Angel, Little Monkey”; faintly reminiscent of labelmates Long Fin Killie, it highlights all that made and still makes Pram so specialListening to these albums again makes me appreciate how fortunate I was to be experiencing the wave of Nineties independent at the moment. These albums are timeless, and genuinely sound as fresh and urgent and questing now as they did twenty-odd years ago

-Mr Olivetti-