Martin Archer is one very busy man. As well as running the Discus label, he seems intent on putting out album after album with various different collaborators and under numerous styles. It doesn’t feel like so very long since the Anthropology Band‘s album rose like an incredible new sun over my world and I have been living with it since, trying to put its two-and-a-half hours of instrumental odyssey into something that makes sense — and doesn’t drift into a 10,000 word treatise on why it is possibly the most expansive and fulfilling jazz-based album it has been my pleasure to sink into.

Martin Archer is one very busy man. As well as running the Discus label, he seems intent on putting out album after album with various different collaborators and under numerous styles. It doesn’t feel like so very long since the Anthropology Band‘s album rose like an incredible new sun over my world and I have been living with it since, trying to put its two-and-a-half hours of instrumental odyssey into something that makes sense — and doesn’t drift into a 10,000 word treatise on why it is possibly the most expansive and fulfilling jazz-based album it has been my pleasure to sink into.

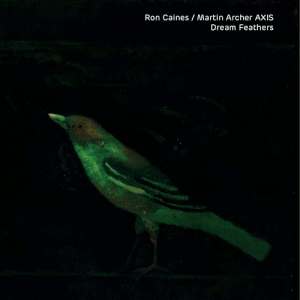

In the time that I have been dwelling on that, another album has appeared, Dream Feathers, this time another collaboration with Ron Caines, in the wake of 2018’s Les Oiseaux De Matisse and sweeping up a whole host of outstanding players into an subtle seven-piece, including Laura Cole on piano and Johnny Hunter on drums, that sits back and allows Ron’s compositions to unfold under their watchful eyes.

The album is bookended by two long tracks, and these allow the assorted players plenty of space to assert themselves. On the whole, Ron’s pieces have a kind of nebulous, romantic air that leans away from the sort of improv I was half expecting, and instead contains a kind of smoky sensuality that emits from the speakers like a flutter of feathers. That smooth smokiness, when allied to Laura’s deep-tracking piano, lends a dusky atmosphere made all the more mysterious by the sounds of shadow and stealth that Hervé Perez and Anton Hunter draw from electronic sources. The sax moves in a slight daze, as if its attention is wandering, and the subtle textures can drop in and out of focus when you are least expecting them. The other players use these opportunities to proffer a little abstraction, a kind of kaleidoscope of visions in which the sax dances, undulating in the scant twilight. There is much attention played to the sax, but you can’t help escaping into the background at times; the rolling drums on “African Violets” highlighting the sweetness of the sax in this modern setting. The sawing double bass of Gus Garside that appears on “Marcel” is a welcome lip-smacking addition to the flickering drums as the players feel each other out, watching the movements in candlelight reflected across the room. The textures on “Uccello/1934” are irresistible, and the reverb lays like wreaths of smoke around Ron’s head. Even the follow-through of his breath is caught by the crystalline production and almost puts you in the room with them. The repetitive, circulating piano motif and soft bass find you drifting through patterns of light and shade, with the infusion of electronics nudging at Ron’s closed eyes as the rest of the players watch rapt.The measured use of electronic textures lend an air of external influence to the pieces, and at times shake us from the dreamlike air that envelopes the sax. But there are opportunities for things to be stripped right down to a more familiar jazz-based sound as on the delightful piano and sax duet of “Nico” and the barely accompanied shoreline sax meandering of “Scratch Line” with the sound of seagulls and trickle of water putting you right there in the open. The piano is extraordinarily resonant on the final track “Almazon/1934 reprise”, and acts almost as a kind of warning to the carefree sax — but a warning against what? The guitar casts eerie spectres, and the slap and clatter of the drums is urgent. It feels as though they are playing in the open air, but close to an airport, the rush of take-off murmuring in the distance and when that has passed, feats of birds appear in a close-by copse, attracted by the unfolding soundscape drifting from the instruments, painting a picture of harmony and tension captured by players at the height of their game.

-Mr Olivetti-