Poet, film-maker, writer, psychonaut, psychotherapist, magician, mystic, visionary, graphic novelist, joker, smoker, midnight toker … the list of pertinent adjectives just seems to go on and on. To paraphrase Voltaire, if Alejandro Jodorowsky did not exist, it would be necessary for us to invent him.

Poet, film-maker, writer, psychonaut, psychotherapist, magician, mystic, visionary, graphic novelist, joker, smoker, midnight toker … the list of pertinent adjectives just seems to go on and on. To paraphrase Voltaire, if Alejandro Jodorowsky did not exist, it would be necessary for us to invent him.

Through his unusual personal lineage – born to Jewish Ukrainian parents in Chile – creatively, Jodorowsky has always embodied a near singular collision of European high art and Latin American magical (sur)realism. Despite having been born in 1929, and thus being over thirty before the Sixties even began, Jod’s unique and psychedelic approach to writing, art and film-making clicked into place during that decade like a machine-tooled piece of jigsaw, its liberated, vision-questing aesthetic perfectly in tune with the new age of Aquarius: from John Lennon to Dennis Hopper, Jod made effective personal and working relationships with many of the leading luminaries of the era.

Jod’s breakthrough into the mainstream came with his legendary acid western, 1970’s El Topo, in which he plays a black-clad gunslinger searching for enlightenment amidst religious, social, psycho-sexual and occult happenings. Oh, and dwarves. Always lots of dwarves.Madcap even for the times, El Topo became an unlikely hit du jour, its nocturnal screenings at New York’s Elgin Theatre eventually spawning the ‘midnight movie’ scene – late night cinematic lunacy for night owls, stoners, lovers, emergent alternative types and all those generally seeking an underground in which they could define themselves apart from the commercial and the popular, and stake out a territory of difference. It was through the doors opened by the success of El Topo that John Waters, David Lynch and host of other future cinematic seers stepped, each beginning their own personal ascent of the mountain.

And on the theme of mountains, it was Jod’s follow up to El Topo, 1973’s The Holy Mountain, which really sealed his reputation as the filmic maverick magus par excellence. Financed with one million pounds donated by The Beatles’ notorious manager-cum-shyster Allen Klein, The Holy Mountain turned every dial up to eleven: the occult and alchemical symbolism, the crazed religious imagery, the LSD, the colour, the hats; it positively overflows with retina-busting detail and hidden meaning. Oh yes, and dwarves. The ending, in which Jodorowky starts to deconstruct the very film itself, is still a jaw-dropping piece of cinema.However, just at the point where Jodorowsky’s creativity in film should have pushed on still further, a pair of malignant gremlins contrived to derail this trajectory entirely: firstly, a falling out with Allen Klein lead to both El Topo and The Holy Mountain being pulled from circulation for many years and, secondly, Dune. The story of Jodorowsky’s Dune has now become so legendary that entire documentaries have been made about it, and, despite the film never actually having been made, its influence rippled out over decades of science fiction cinema.

Managing to make only one more film during the Seventies, 1979’s bafflingly terrible Tusk, about one girl’s relationship with an elephant, as the changed political, spiritual and economic decade of the Eighties dawned, Jod disappeared from view entirely.

In retrospect, in the era of the nascent Jerry Bruckheimer ‘high concept’ Hollywood product, it is difficult to know what other course of action he might have taken. David Lynch, being superficially much ‘straighter’ and, by all accounts a very affable man, could wear sheep’s clothing during those years, his inner wolf bursting forth periodically with the likes of Blue Velvet. The stratospheric global success of Twin Peaks shortly thereafter then made Lynch – for a while at least – untouchable.It is almost impossible to imagine Jodorowsky following the same parabola, his volatile character, spiritual élan and unconstrained lust for life would never have allowed for easy discussion over a balance sheet in a boardroom finance meeting. Yet, with culture still able to change apace in those days, the latter part of the Eighties saw revived interest in all things counter-cultural: the refuges of the mainstream seeking meaning and fulfilment in art – and artists – who represented genuine alternatives to the ever-blander fare on offer in commercial music and film. What better time for the renegade maestro to finally make his return?

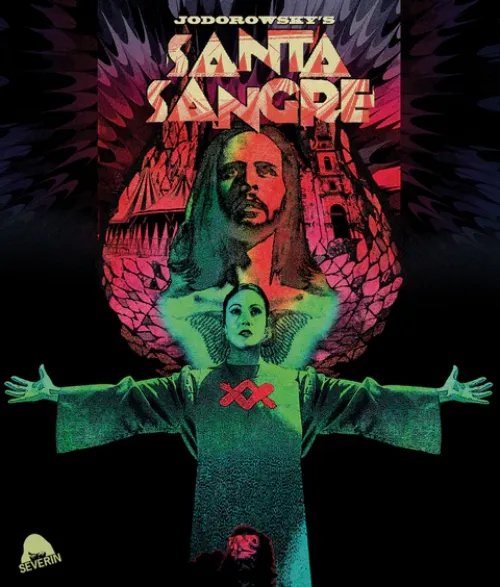

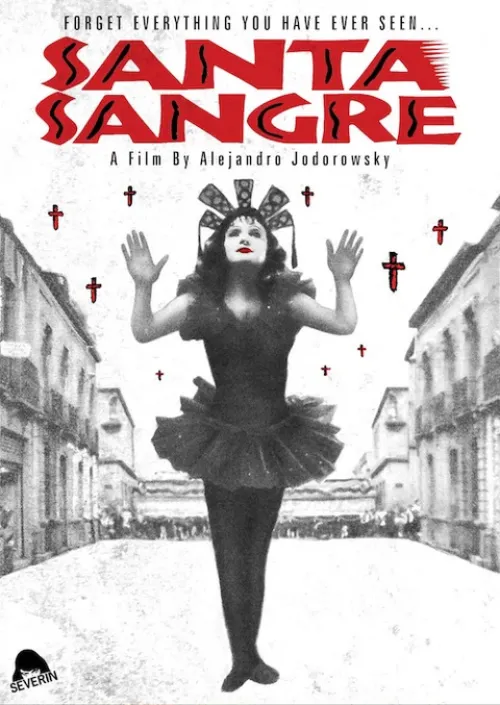

And so, with a flourish, 1989 at long last saw the release of Jodorowsky’s sixth film, Santa Sangre. Teaming up with another cinematic macher fallen on leaner times, producer Claudio ‘brother of Dario’ Argento, together this unsettling twosome unleashed a genre-busting, eyeball-popping masterpiece which Roger Ebert once called “a horror film, one of the greatest.” Whether one subscribes entirely to that description or not, and the influence of the classic Argento giallo is undeniably present, Santa Sangre is prime Jod, updated for the dawn of the 1990s, retaining all his signature concerns and conceits, whilst also adhering to the slicker aesthetic of the time. Most fans see it as probably the most accessible of his canon, yet one which sacrifices nothing in terms of authenticity and uniqueness. A reviewer is never thanked for spoilers, intentional or not, added to which trying to describe Jodorowsky’s films in terms of mere narrative is not only self-defeating but in fact to completely miss their very point – Jodorowsky’s are films in which the act of interpretation is singularly the most meaningful part of the activity. In the kaleidoscopic flux of symbols, imagery and metaphor, no viewer is likely to be able to decipher it all. However, like alchemy, in the acting of watching, the process does its work.It gives nothing away to say that the film’s story deals with the effects of childhood trauma (including some very interesting parental and gender-based complications) on the film’s protagonist Fenix (played by two of Jodorowsky’s own sons, Adan and Axel), and which play out later amidst madness and murder in his adult life. The darkness of the theme, shot through with both Freudian and surrealist imagery, is nevertheless given an ending that whilst ambiguous, is also undeniably uplifting and redemptive.

Watching it again after thirty-five years confirms Jodorowsky’s almost unrivalled ability to contain opposites: the beautiful and the repellent, the elevating and the degrading, the rational and the insane. Being the magician that he is, he somehow reconciles these chaotic contradictions, achieving a dialectic of combination and offering us up the cinematic Philosopher’s Stone that results. This is perfectly encapsulated in the unforgettable scene which occurs when an elephant dies in the circus that provides the milieu of Fenix’s childhood: the body of the unhappy jumbo is placed into a gigantic coffin and then hurled over the edge of a steep cliff down into the municipal dump below, whereafter swarms of poverty-stricken peasants descend upon it, intent on claiming what little they can of the elephant’s earthly remains to satisfy their gnawing hunger. It is a striking, comedic, horrifying, beautiful, repulsive scene, and it is hard to think of any other film-maker who could have produced it without seeming gratuitous or pointless offensive. Somehow Jod has always been able to skip between the raindrops of the tasteless and emerge with his clothing dry.

This is perfectly encapsulated in the unforgettable scene which occurs when an elephant dies in the circus that provides the milieu of Fenix’s childhood: the body of the unhappy jumbo is placed into a gigantic coffin and then hurled over the edge of a steep cliff down into the municipal dump below, whereafter swarms of poverty-stricken peasants descend upon it, intent on claiming what little they can of the elephant’s earthly remains to satisfy their gnawing hunger. It is a striking, comedic, horrifying, beautiful, repulsive scene, and it is hard to think of any other film-maker who could have produced it without seeming gratuitous or pointless offensive. Somehow Jod has always been able to skip between the raindrops of the tasteless and emerge with his clothing dry.

Let us instead be thankfully that Jodorowsky’s films exist at all, so unlikely do they really seem, magically real fever dreams in which we can all participate. At ninety-five, it seems increasingly unlikely that he will now make another film – although rarely would I more delighted to be proved wrong – but Santa Sangre remains a stunning film with which to celebrate Jodorowsky’s singular creative north star.

-David Solomons-