Strange Attractor Press (book) / State51 (LP)

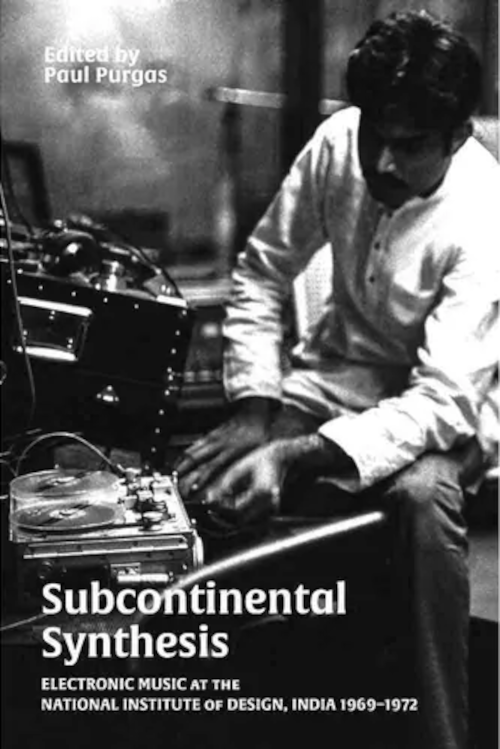

What’s being reviewed here is two things: a book, Subcontinental Synthesis: Electronic Music at the National Institute of Design, India 1969–1972 , edited by Paul Purgas, and a record, The NID Tapes – Electronic Music From India 1969-72. The NID of the LP’s title refers to the National Institute of Design, a home for electronic music within India of the late 1960s. The book is a more expansive look at electronic music in that era, and one is a taster for the other.

What’s being reviewed here is two things: a book, Subcontinental Synthesis: Electronic Music at the National Institute of Design, India 1969–1972 , edited by Paul Purgas, and a record, The NID Tapes – Electronic Music From India 1969-72. The NID of the LP’s title refers to the National Institute of Design, a home for electronic music within India of the late 1960s. The book is a more expansive look at electronic music in that era, and one is a taster for the other.

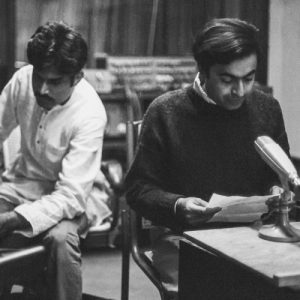

In it we have pencil sketches of that world — private benefactors who were supportive of Indian independence and Indian art projects. Dialogues around the problems of non-Indian influences in Indian culture. Discussion of the differences between Western electronic music at that time (influenced strongly by harmonic theory) and the Indian music’s norms (monodism, rhythmic complexity). The electronic music produced at the NID was done by a mix of people, amateurs and musicians alike. And it was done with a substantial degree of influence from well-known avant-garde names like John Cage and David Tudor.

It’s a lovely book and has a satisfying range of voices and tones — from the descriptive ‘this is the NID’ to more personal, anecdotal work. And it’s got an important reciprocity with the LP (a download of which is included when buying the book directly from Strange Attractor) in a way that’s often lost in the liner note-less world of the twenty-first century. So we learn that Jinraj Joshipura‘s work is informed by his being a non-musician, and yet still David Tudor being happy to show him the ropes; he explains the sonic world he’s creating in his “Space Liner” pieces (two parts here on this disc) in some detail. The music itself is bolstered by these explanations, the sense of creating disquietingly futuristic, sci-fi informed worlds. There’s plenty also that alludes to why Indian electronic music isn’t well-known, the way that Euro-American electronic music from ’50s-’60s is. Part of it is due to tradition — as mentioned, Western traditions are familiar with harmonies and the electronic means is more native to those traditions (arguably). The counter to that in this book is that there’s at least the potential that this music is more radical, insofar as it’s not building on but exploding local traditions. There’s some important structural (or cultural, political) points raised throughout the book, such as:[A]n issue even more pressing than the relative lack of gear — the fact that there isn’t a massive recorded legacy of Indian rock and electronic music from that time. There aren’t piles and piles of full-length albums. The recordings that exist are scattered, in a large part because the entire infrastructure of these scenes also didn’t really exist in India. (Geeta Dayaal, p50)

This is further expanded to illustrate that not only is electronic music new and expensive (and the hardware often far away), there’s the additional impediment that the means of preserving musical culture in India is not well-suited. Musical education is still largely guru–shisya, classism (or more particularly, casteism) is still a large part of the culture. Nevertheless, there’s a strong sense that women are by no means secondary in this collection, and the world of the NID; the relationship between Gita Sarabhai and John Cage seems reciprocal, and plenty of the composers here are women (perhaps monied women, but women nevertheless). Perhaps the most antagonising part of the book relates to Gita Sarabhai — it’s mentioned several times that a recording called “Frequencies In Square And Sine Wave Of Chromatic Scale (Indian)” is in the archives, and that it’s an exploration of Indian svaras (notes), and that it’s twenty-plus minutes long. It is not on the album, so it may be that Sarabhai’s most substantial piece is languishing in an archive somewhere in Ahmedabad. As it is her pieces on the disc are among the more delicate and rewarding, albeit short — “Gitaben’s Composition II” in particular is astonishing, a luscious drone that’s picked and scabbed away at by imperceptible sources, irrevocably fraying in a way that’s most uncanny. The collection on its own is certainly compelling enough — plenty of squelchy timbre and gorgeous sounds. While the book does slip in at least one ‘proto-techno’ description (erroneously, I’d argue), there is plenty of other effects that came to be (over-)used in later electronic music — SC Sharma‘s “Dance Music” has generous use of the kind of violent glitchy clicks that service as rhythm instruments; plenty of early electronic music charm — IS Mathur‘s “My Birds”, which uses some sharp note manipulation to emulate bird whistles. It’s not Olivier Messiaen, but it’s also not like US academic musicians who tend to be more literal with their ‘bird sounds’, and less about using the tech to emulate.

The collection on its own is certainly compelling enough — plenty of squelchy timbre and gorgeous sounds. While the book does slip in at least one ‘proto-techno’ description (erroneously, I’d argue), there is plenty of other effects that came to be (over-)used in later electronic music — SC Sharma‘s “Dance Music” has generous use of the kind of violent glitchy clicks that service as rhythm instruments; plenty of early electronic music charm — IS Mathur‘s “My Birds”, which uses some sharp note manipulation to emulate bird whistles. It’s not Olivier Messiaen, but it’s also not like US academic musicians who tend to be more literal with their ‘bird sounds’, and less about using the tech to emulate.

The synthesizer legitimized and validated the right to experiment and innovate. This experimental spirit and the emergent ideas followed the sounds to reach the vibrant areas of cultural life like inaudible ripples, from film music to television, popular music to radio, and everyday practices. Although the arrival of the synthesizer might have seemed disjunct, the ramifications were complexly enmeshed with the subcontinent’s desire to self-determine. (Budhatiya Chattopadhyay, p6)

…and there’s plenty of evidence of that on the record. While there’s certainly elements of emulating existing practices (SC Sharma’s “Electronic Sounds Created On Moog I”, all beepy and overlapping melodies), there’s plenty enough that’s deep into timbral evocations and sound-for-sound in an unhewn, distinctly different way to Cage et al (SC Sharma’s “Wind & Bubbles” — perhaps showing that one person given the space to experiment can have many voices).A lovely record and a lovely book. It’s lovely to have the Indian context laid bare and it’s lovely to have a range of voices, in writing and in sound, telling their stories without grandiose intervention from well-meaning Westerners.

-Kev Nickells-