It was Voltaire who perhaps put it best when he reviewed the first Suicide album on its original appearance in 1977: “If Suicide did not exist, it would be necessary to invent them”. A punk band before the term existed, a rock band without guitars, a duo who could cow an entire room of people, like the platypus, Suicide were an entity so unbelievable that they should surely not have existed in nature. Yet exist they most certainly did.

It was Voltaire who perhaps put it best when he reviewed the first Suicide album on its original appearance in 1977: “If Suicide did not exist, it would be necessary to invent them”. A punk band before the term existed, a rock band without guitars, a duo who could cow an entire room of people, like the platypus, Suicide were an entity so unbelievable that they should surely not have existed in nature. Yet exist they most certainly did.

Like The Dolls, Suicide materialised amidst the mounting economic and civic tumult of New York City in the late 1960s and early 1970s.i Brooklyn-born Catholic Jew Boruch Alan Bermowitz, a fan of rockabilly music and comic books, had previously had his head turned after witnessing a Stooges show at The Pavilion in Flushing Meadow in the summer of 1969. Inspired by Iggy Pop’s on-stage antics, Alan Suicide (as he was then sometimes known, taking the name from his favourite Ghost Rider comic entitled Satan Suicide) was then creating light sculptures (built from “half-broken TV sets, stolen fluorescent tubes, chains, subway lights, broken glass and other bits of detritus [he] picked up from the streets”) and making far-flung electronic experiments at the Museum: Project of Living Artists, a 24-hour downtown workshop / performance art space at 729 Broadway, publicly funded by the New York State Council on the Arts.

One inclement night, Bronx-born Martin Reverby, musical obsessive and former pupil of bebop legend Lenny Trisanto, ducked into the space to avoid a particularly cold and unpleasant downpour outside. Finding Vega and fellow artist Paul Liebegott summoning dissonant electronic noise and feedback from a guitar and some speakers, Rev proceeded to lock immediately into the vibe, pick up some rusty industrial springs that were lying discarded nearby and begin pounding out an accompanying rhythm by banging them against the floor. Soon afterwards, in a pleasing symmetry, Vega stumbled into a performance by Rev’s confrontational large unit outfit Reverend B, that night comprising a dozen musicians, to whose number an impressed Vega then duly added himself.

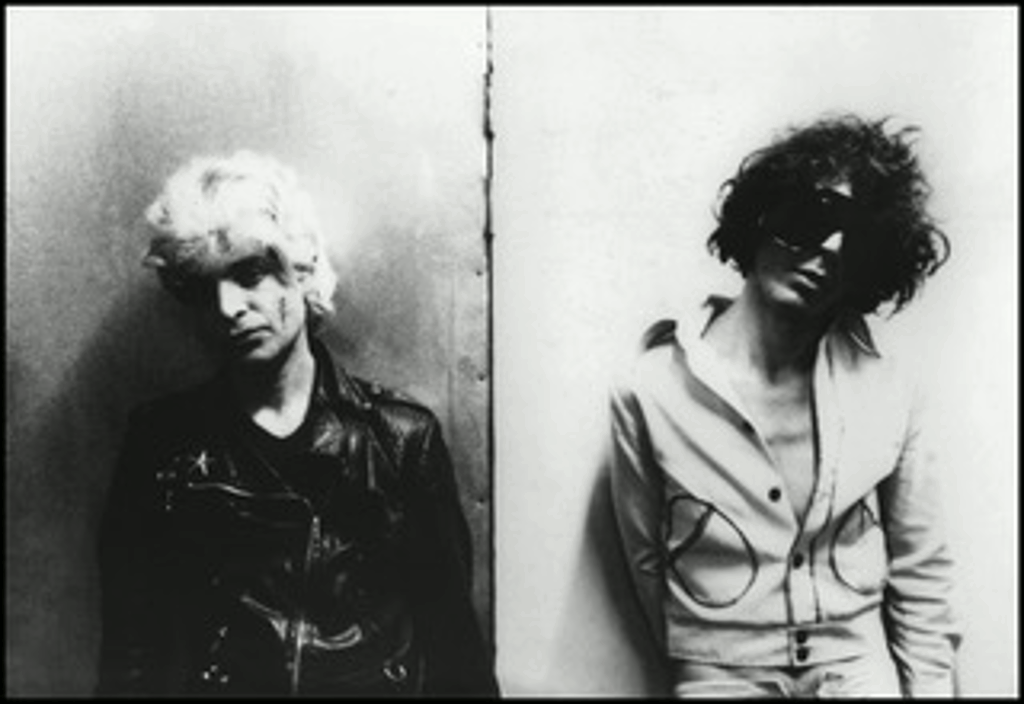

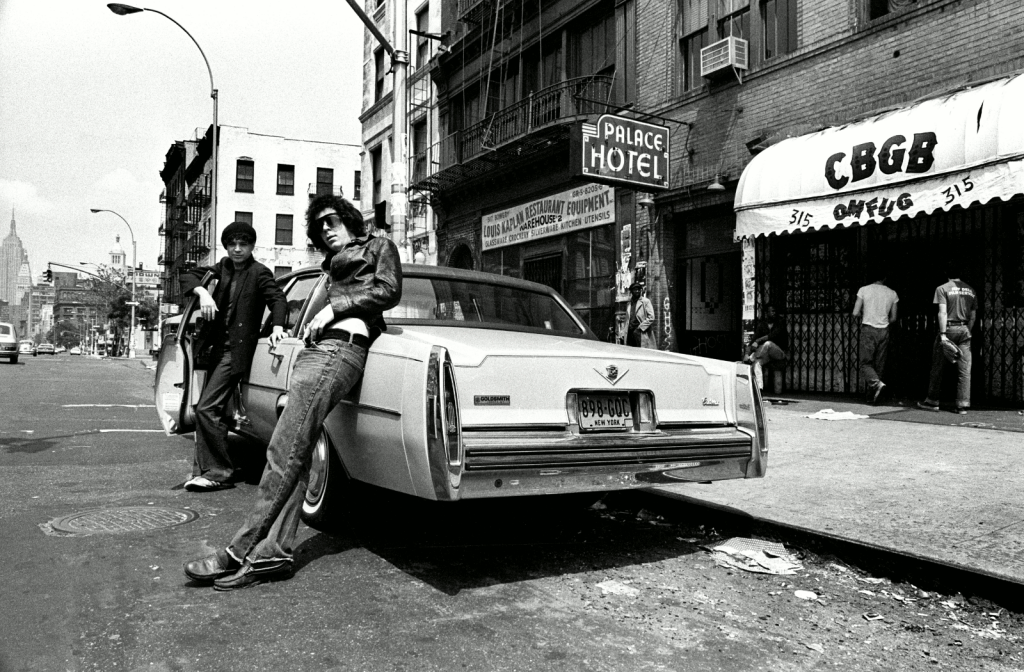

The duoii – initially calling themselves Nasty Cut and Marty Maniac, but soon rechristened as Alan Vega and Martin Rev, and dressed in the stylings of avant-futuro street thugs, all outsize shades, leather jackets, headbands and curled lip sneers – wasted no time in putting their quarrelsome musical output in front of live audience, first at the Project of Living Artists and other local galleries, and soon afterwards across the coterie of small venues which would form the backbone of the city’s legendary late 1970s circuit. By only Suicide’s second show, in October 1970, flyers were already proclaiming the event to be a “Punk Music Mass”, which is often cited as a first example of a band using the word “punk” in an official context to describe their music.

Nomenclature aside, the effect of the band’s shows was immediately electric, terrifying and inspiring those that witnessed them. In his 1990s biography Poison Heart: Surviving the Ramones, Dee Dee Ramone remarked:When I first saw Alan Vega and Suicide, I pulled out my 007 knife and palmed it behind my wrist. To be frank, I was a little worried. If Iggy had created a Frankenstein, it was Alan Vega. When Alan jumped into the sparse audience, it was a bit too much for me. I didn’t know what was going to happen. He [was] a very serious performer.

Having been marked indelibly by Iggy’s performance in Flushing Meadow, Vega gradually began to perfect a similarly combative and confrontational live persona:People were looking to be entertained, but I hated the idea of going to a concert in search of fun. Our attitude was, “Fuck you buddy, you’re getting the street right back in your face. And some”. At one of our first shows, there was a guy in the audience who’d brought this trombone. I jumped into the audience, fell over and knocked the slide out of his trombone. These South Americans took real offence to that. So they immediately attacked us with chairs, tables, anything they could get their hands on. That became the norm. I started carrying a bicycle chain on stage, figuring, if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em. If the violence got really bad, what I’d do was smash a bottle and start cutting my face up. That seemed to have a calming effect on the crowd. I guess they reasoned that I was so fucking nuts that nothing they could do would bother me. I figured out a way of doing it so that I drew a lot of blood but I wouldn’t be scarred for life. I had it down to a fine art. Another ploy I had was to lock the exit doors so nobody could escape. That was the ultimate “fuck you”, as far as I was concerned.

It was 1975, though, a half-decade into the band’s existence, that was to prove Suicide’s pivotal year. Whilst most bands, after five years of steady state, would either have already disintegrated or at the least be at the point of rupture, Suicide typically managed to buck such a trend. Instead, transforming themselves technologically and musically, they gradually emerged from their slow, chrysalis-like development as a different kind of beast. With more heft in the bank balance, Martin Rev acquired a second-hand Seeburg Rhythm Prince (an elegant gold-fronted drum machine produced in the late 1960s), using it to supplement his existing set-up of Farfisa keyboard, Electro-Harmonix distortion devices and other electronics, and thus hugely expanding the band’s range of musical possibilities.

For his part, Vega obtained a two-track recorder, and this equipment allowed the band to call a halt to live performance and instead focus their time around writing and recording a whole batch of new material. Decamping to Vega’s basement studio at the Project of Living Artists (now relocated to Greene Street), Suicide recorded “Speed Queen”, “Creature Feature”, “Space Blue Mambo”, “Be My Dream” and “C’mon Babe” (an early iteration of “Cheree”) amongst others. It was this material which later appeared on the legendary Roir tape release Half Alive and the late 1990s Blast First CD The First Rehearsal Tapes. Other material on those releases (including “Dreams”, an early version of “Dream Baby Dream”) was culled from another recording session they undertook at Sundragon Studio on West 20th Street, where The Ramones would record Leave Home the following year, and Talking Heads their début album in 1977.

Whilst a first recording was most definitely a milestone (though as one six years in the making it hardly betokened a meteoric career rise), through the year, as the transformed New York music scene began to catch the watchful eye of the music industry, Suicide’s contemporaries (The Ramones, Television, The Patti Smith Group, Blondie, Talking Heads) were gradually signed one by one to major record labels. Suicide themselves, however, continued to be conspicuously overlooked, and there was a distinct danger that the band would remain ever the bridesmaid and never the bride; Suicide’s dangerous and unpredictable energy, which had done so much to galvanise the action that was making the scene so attractive, also made them a distinctly risky investment for any industry moguls hoping to snap up a tasty morsel of the local happenings.

Once again though, at this crucial juncture sweet Lady Luck smiled down at Vega and Rev, when the latter bumped into Marty Thau one day in the East Village. Although Thau had always carried something of a torch for Suicide, earlier on in the 1970s he had been too preoccupied with marshalling the chaos of The New York Dolls to be able to capitalise on any potential working partnership with them. Of this chance meeting, Thau later recalled:[Rev said] “we’re playing at Max’s Kansas City in a couple of weeks. Would you like to come to the show?” And I said, “Sure, I’d love to.” So I went to the show and I couldn’t believe how great I thought they were. Even better than they were earlier. Certainly more unusual. I never thought they were really commercial but I enjoyed what they were doing and I respected what they were doing.

Putting some skin immediately in the game, by mid-summer Thau had offered Suicide a one-year recording contract with his newly formed Red Star label, soon bringing them the studio, and splitting production duties with Craig Leon. Using Ultima Studio in Blauveltv (twenty or so miles north of New York on the Jersey shoreline, and referred to by Vega as the “middle of nowheresville”), the seven tracks that comprise Suicide, (together with the “Cheree” / “I Remember” single), were completed in only four days in July on a budget of around $4,000. Thau’s good auspices apart, though the bucks may not have been particularly big, they bought an awful lot of bang…

Bursting out of the speakers like a trash Cadillac roaring straight towards you across the baking blacktop, “Ghost Rider” is an epic piece of mythic Americana, oppressive, relentless and brutal. Craig Leon’s dub-like use of echo (learned through honing his chops alongside Lee “Scratch” Perry at Black Ark Studios), add a further layer of distinctiveness to the band’s sound right from the offset. Contemporary with the world-historic work that Kraftwerk were doing in Düsseldorf, though there is a similar animating aesthetic, Suicide reeks of the dirty sidewalks and nocturnal urban sleaze of New York City, not the gleaming technological futurism of Wirtschaftswunder Germany.vi

“Rocket USA” describes doomsday to a pounding electronic jitterbug, halfway between Manson Family-style creepy-crawling and the Hellfire of the nuclear apocalypse. “Cheree”, already a well-seasoned piece by this stage, shows the delicate side of Suicide and for all their tough guy combative appearance, they certainly had one. Vega’s vocals are so plaintive, redolent of the crooners popular in his youth,vii whilst Rev’s delicate tinkling keyboards sit quietly in the background, tugging at the heartstrings. The two-minute “Johnny” is a classic piece of rock and roll, transfigured for the keyboard, and detailing the life of the titular delinquent so perfectly that you can almost smell the hair oil and hear the menacing swish of his switchblade.

It’s sobering to remember that when the song was written, ideas about and understanding of the effects of PTSD on former combatants were not a universally understood currency. Indeed, the very definition of the condition came from studying the effects of the Vietnam War on its former soldiers throughout the latter part of the 1970s.viii Alan Vega may not have been a clinical psychologist, but he was way ahead of the curve in examining the phenomenon culturally. Vega commented years later than several people had remarked to him that “Frankie Teardrop” was “the song that Lou Reed wished he had written”. The album closes with the sombre “Che”, its melancholy descending chord structure strangely reminiscent of liturgical music and giving the album’s end a curiously longing, spiritual feel.

Rev later said that he was:

…not unhappy with how it sounded, which is not always the case when you hear your own work. It did not sound like us playing live in a club – an album can’t sound as big and incredibly immense as we did in clubs – that threw a few people off initially. But I felt positive about it. I don’t remember having any negative feelings about it at all.

Predictably, given the band’s uncompromising stance in all things, not least those musical, the album was greeted by howls of baffled outrage from reviewers in America (save naturally Lester Bangs, who hailed its arrival with a typically bullish piece entitled “The Joy of Suicide”). With the UK firmly in the full grip of punk’s annus mirabilis, however, reviews there were considerably better. And although, due to Red Star’s limited resources, the album was never originally destined for overseas release, Howard Thompson from the UK’s Bronze Records showed considerable foresight, tenacity and improvisation by travelling to New York to see the band live at Max’s Kansas City and thereafter swiftly arranging both a European release and a string of support data alongside Elvis Costello and The Clash in order to introduce them to a new and sympathetic audiences.Suicide’s European support gigs of 1978 have since gone on to become the stuff of copper-bottomed rock legend, from the riot that ensued in Brussels in June (later issued first as a bootleg then later a legitimate release) to the infamous – though contested – “axe incident” at the Glasgow show the following month.ix

Like all the best stories, many who claimed to have been at the Glasgow Apollo weren’t, and those that were often could not agree on what actually happened. Vega, the eye of the hurricane, recalled:[T]he show in Glasgow in 1978 when someone threw an axe at my head. We were supporting The Clash and I guess we were too punk even for the punk crowd. They hated us. I taunted them with, “You fuckers have to live through us to get to the main band”. That’s when the axe came towards my head, missing me by a whisker. It was surreal, man. I felt like I was in a 3-D John Wayne movie. But that was nothing unusual. Every Suicide show felt like World War Three in those days. Every night I thought I was going to get killed. The longer it went on, the more I’d be thinking, “Odds are it’s going to be tonight.”

Several have questioned the veracity of the axe story, though others have sworn blind that it was all true. What was not in doubt, however, was that at the show in Metz (as part of the Third International Science Fiction Festival), one particularly accurate audience member scored a direct hit on Vega with a monkey wrench, causing a scar which he carried ever afterwards. The festival was notable too for its main guest speaker, the estimable Frank Herbert, and for the presentation of a first European screening of David Lynch’s Eraserhead. Oh, truly, it was great in seventy-eight.The best part of a decade into their existence, with an album that critics seemingly hated, and live shows that resembled nothing so much as a war zone, in the topsy-turvy world of Suicide, things were soon looking up. How exactly? We’ll leave the final word to Alan Vega:

Then something very strange happened. We headlined our own tour of Britain and ended up in Edinburgh. Two songs in and there was no riot, which was very, very unusual. Then we started to see people move around. I turned to Marty and said, “Here we go – watch out for flying objects”. To my amazement, people started dancing. I turned back to Marty and said, “We’re finished, our career is over”.

-David Solomons-

i Matters would gradually come to a head at the mid-point of the decade, and on 17 October 1975, New York City reached crisis point. At 4pm that day, $453m of the city’s debts were to become due, but there was only $34m in the financial reserves. If New York could not meet its maturing debt obligations, the city would officially be bankrupt. After some extensive – and savage – political and economic negotiation, the Armageddon scenario was avoided at the last minute. From the 2019 perspective of boom-time New York, it is sobering to consider what might otherwise have happened had a solution not been found at the eleventh hour.

ii In the early days of the band, Suicide were in fact a trio, the third part of the equation being Cool P, AKA Paul Liebegott, who at the time was a sculptor (and later film-maker) working at the Project. Providing rudimentary guitar, Liebegott left the band amicably later in 1970. During the following year, 1971, Suicide remained a trio, with Mari Rev playing drums.

iii A crucial “interregnum venue” between the Andy Warhol 1960s and the CBGB 1970s, the Mercer provided early exposure for The New York Dolls, Wayne County and others. In August 1973 the venue suffered a partial structural collapse.

iv Craig Leon, a lesser-known name on the scene but nevertheless a crucial mover and shaker, would also produce the début albums of The Ramones, Blondie and Richard Hell.

v Although off the beaten track, Ultima already had form as local Jersey boy Bruce Springsteen had recorded his first three albums there. Despite such a pedigree, Ultima is now sadly the Blauvelt Auto Spa car wash. Sic transit Gloria Ultima.

vi Indeed, recognising kindred spirits, when Ralf and Florian were played Suicide by Lester Bangs, they each requested a copy to take home to Germany.

vii Vega was famously older than most people assumed. Though he claimed to have been born in the late 1940s, he had actually been born in 1938, making him almost forty by the time Suicide was recorded. That same year, Joey Ramone was twenty-six and David Byrne twenty-five.

viii PTSD was officially recognised by the American Psychiatric Association in 1980 in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III). One of the earliest and best cinematic examinations of it, First Blood, appeared the following year in 1981. The film ruthlessly dissects the simmering undercurrents that remained unaddressed in America following the war, and Sylvester Stallone’s breakdown at the end of the film is still almost unbearably painful to watch.

ix Whatever the truth about the axe, a delicious flavour of the Glasgow show can be gleaned from audience member Ian Taylor’s belated review.