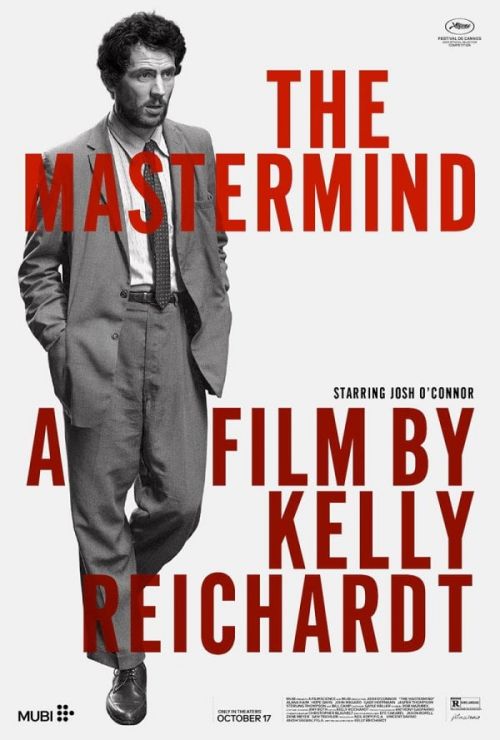

1970s suburbia may be unlikely soil in which an accomplished art thief might grow, but America’s most lackadaisical auteur Kelly Reichardt pulls on her apron and prepares a bijou little garden for him anyway, using the dichotomy of his ordinary family life and the high stakes of his profession as her fertiliser. The genre beats are familiar, but she plays them with her customarily light touch and off-kilter rhythm.

1970s suburbia may be unlikely soil in which an accomplished art thief might grow, but America’s most lackadaisical auteur Kelly Reichardt pulls on her apron and prepares a bijou little garden for him anyway, using the dichotomy of his ordinary family life and the high stakes of his profession as her fertiliser. The genre beats are familiar, but she plays them with her customarily light touch and off-kilter rhythm.

He hides his spoils right under the noses of his wife Alana Haim, while Hope Davis and Bill Camp play his oblivious (Bank of) Mum and Dad with a bruised dignity, their plot function the necessity of repaying debt, and their story function the unspoken yet crushing weight of parental disapproval.

Christopher Blauvelt’s passive, judiciously detailed compositions may drift from side to side from time to time, but mostly they just sit there, an open book of plot-advancing criminal detail if we’re alert enough to detect it. His elegant, sometimes Edward Hopper-esque images tend to bask in the New England sun, slyly observing that these robberies are taking place in broad daylight, albeit compromised by dusk or dawn, or even by the simple intervention of a set of domestic blinds. Interior scenes exude a different kind of warmth in spite of the film’s chilly theme of social alienation, yellow light bulbs showcasing the brown-and-orange décor, costumes and hairstyles of the era just as effortlessly as the minimalist soundtrack, and indeed Reichardt’s subtle, unobtrusive style in general. There’s always been a strain of movie-brat Hollywood in her work, but her relaxed, almost listless tone and her understated sense of humour firmly stamp it with her own brand, qualifying Reichardt’s nostalgia with a true cineaste’s intellectual distance.The Mastermind is one of the better recent entries in Kelly Reichardt’s distinguished career of gently absurdist parables about the futility of human endeavour. She’s curious about the mechanics of theft, and fascinated by its sociological effects on thieves. She dissuades her splendid cast from the slightest hint of emotionalism, much preferring the furrowed brow to the shouting match, thus muting the drama to a slow vibration of realism.

Reichardt’s distended ‘anti-style’ won’t be for everyone, especially those expecting a cheekier, more animated kind of heist movie. But her devotees will be delighted to pick the brain of this elaborate anecdote.-Stew Mott-