Église Saint-Merri, Paris

Église Saint-Merri, Paris

9 April 2015

Paris’s historic Église Saint-Merri is the scene for the more sedate concerts in Sonic Protest‘s busy festival schedule of gigs which take place across the city and its environs over a very long weekend. The music which unfolds beneath the multi-coloured illuminations that scatter across the ranks of cherubim, illuminate the stained-glass windows and fall upon the various sculptures and multimedia installations which are scattered among its chilled stone walls tonight is nothing if not unusual and occasionally suitably uplifting.

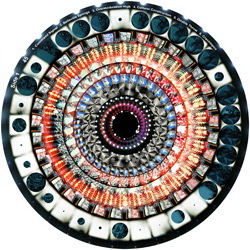

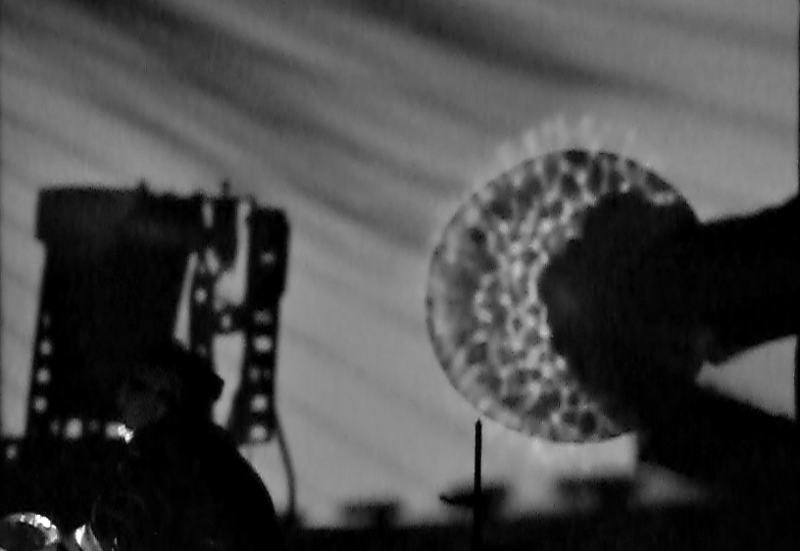

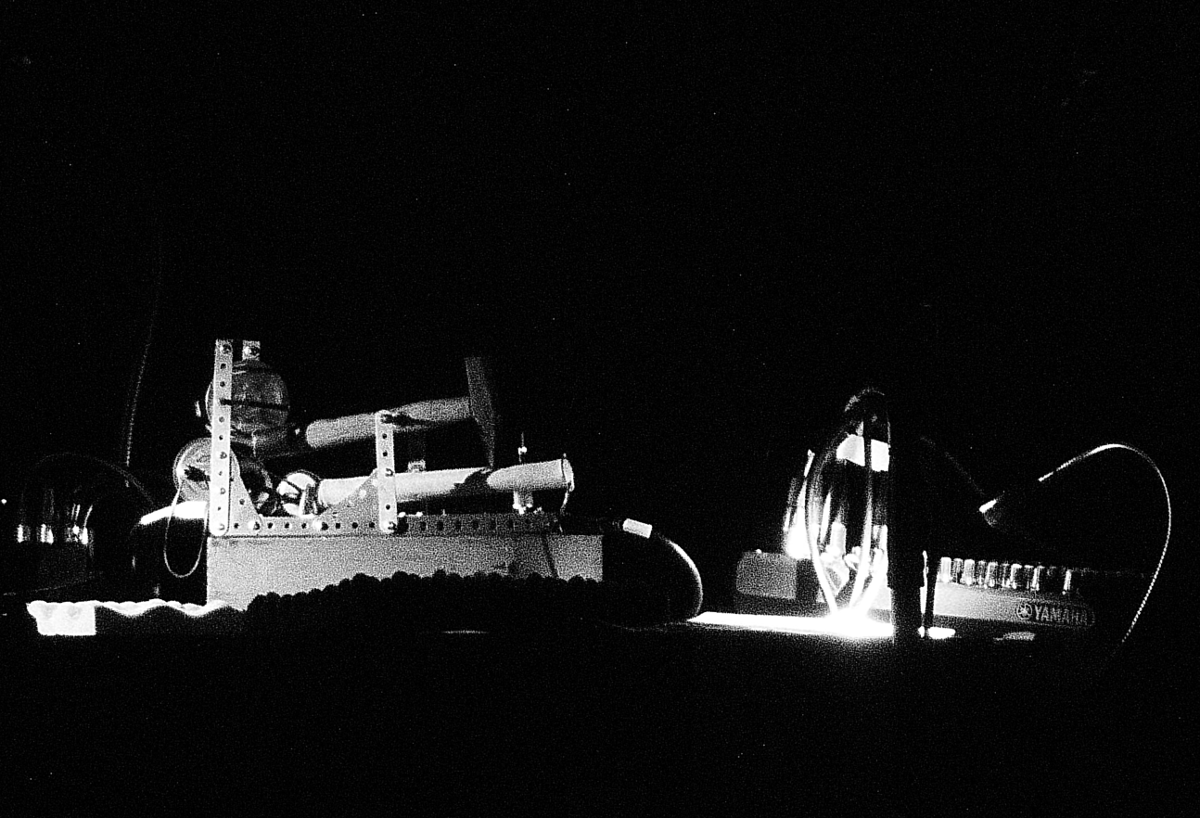

The first highlight of the evening comes when Pierre Bastien and Emmanuelle Parrenin (playing together tonight as Motus) bring out a selection of instruments and household objects, including harp, antique coffee pot, kazoo and swanee whistle. They proceed to play them over a projected video of hands wandering across a piano keyboard, the soundtrack to which forms part of their accompaniment. This continues throughout most of their set in rambling jazz-improv style, all underpinned by the fascinating mechanical instruments which Bastien has been using for several decades now to trip up expectations of how non-human rhythms can be arranged. Perhaps Motus ramble somewhat too, but pleasantly so, deploying yet more paraphernalia such as scissors and other kipple to throw their silhouettes onto the tinkling ivories on the screen at the end of the church in a shadow puppet show of a decidedly avant-garde kind. Bastien deploys a whole battery of mechanical music-making devices, including a pendulum instrument which beats time like a clock while he and Perrennin respectively bow and pluck their more conventional instruments. There’s a self-brushing string thing, which resembles a harp placed on its side to be stroked softly by motorised shaving brushes, and a prepared (not to say highly modified) trumpet with what looks – and sounds – like a bowl of water placed at its end. Each instrument gets its turn in the spotlight as Motus’ set unfolds in a flow of one new, extraordinary or simply delightful sound after another.

Bastien deploys a whole battery of mechanical music-making devices, including a pendulum instrument which beats time like a clock while he and Perrennin respectively bow and pluck their more conventional instruments. There’s a self-brushing string thing, which resembles a harp placed on its side to be stroked softly by motorised shaving brushes, and a prepared (not to say highly modified) trumpet with what looks – and sounds – like a bowl of water placed at its end. Each instrument gets its turn in the spotlight as Motus’ set unfolds in a flow of one new, extraordinary or simply delightful sound after another. At one point they switch to a droning hurdy-gurdy melody, the mood sliding into folkier territory of an ageless kind that suits the surroundings rather well. As Bastien’s muted cornet buzzes a counterpoint to Parrenin’s spine-tingling ancient melody, she intones a reading strongly over the cyclic woodblock rhythms hammered out by one of Bastien’s contraptions which resembles a drum machine as devised by Leonardo da Vinci. The cornet morphs and multiplies in reverberent textures and wandering discordances, and Perrenin makes deft use of a glass bowl played Tibetan style as well as some subtle electric guitar. It’s all very clever, and more than a little impressive to witness played live.

At one point they switch to a droning hurdy-gurdy melody, the mood sliding into folkier territory of an ageless kind that suits the surroundings rather well. As Bastien’s muted cornet buzzes a counterpoint to Parrenin’s spine-tingling ancient melody, she intones a reading strongly over the cyclic woodblock rhythms hammered out by one of Bastien’s contraptions which resembles a drum machine as devised by Leonardo da Vinci. The cornet morphs and multiplies in reverberent textures and wandering discordances, and Perrenin makes deft use of a glass bowl played Tibetan style as well as some subtle electric guitar. It’s all very clever, and more than a little impressive to witness played live. The main event concludes the evening, as The Necks coalesce into their familiar yet ever-different form beneath the mighty organ pipes and what looks like a very ornate ormolu church clock stuck at quarter to twelve, while red-lit cherubim and angels look down from the arched vault above. Nearly fifty solid minutes of rapt concentration of the trio and audience alike follows, each breath in the room held taut in anticipation of some radical change in the constant yet ever-still motion of the music.

The main event concludes the evening, as The Necks coalesce into their familiar yet ever-different form beneath the mighty organ pipes and what looks like a very ornate ormolu church clock stuck at quarter to twelve, while red-lit cherubim and angels look down from the arched vault above. Nearly fifty solid minutes of rapt concentration of the trio and audience alike follows, each breath in the room held taut in anticipation of some radical change in the constant yet ever-still motion of the music.

The attention which The Necks demand and deserve is maintained throughout, even despite an initial clattering from across the church, perhaps from the direction of the quite extensive temporary bar area (what would Jesus think? And did the wine start out as water before it filled the plastic glasses?) which breaks the spell somewhat, though the interruption is thankfully brief.

The attention which The Necks demand and deserve is maintained throughout, even despite an initial clattering from across the church, perhaps from the direction of the quite extensive temporary bar area (what would Jesus think? And did the wine start out as water before it filled the plastic glasses?) which breaks the spell somewhat, though the interruption is thankfully brief.

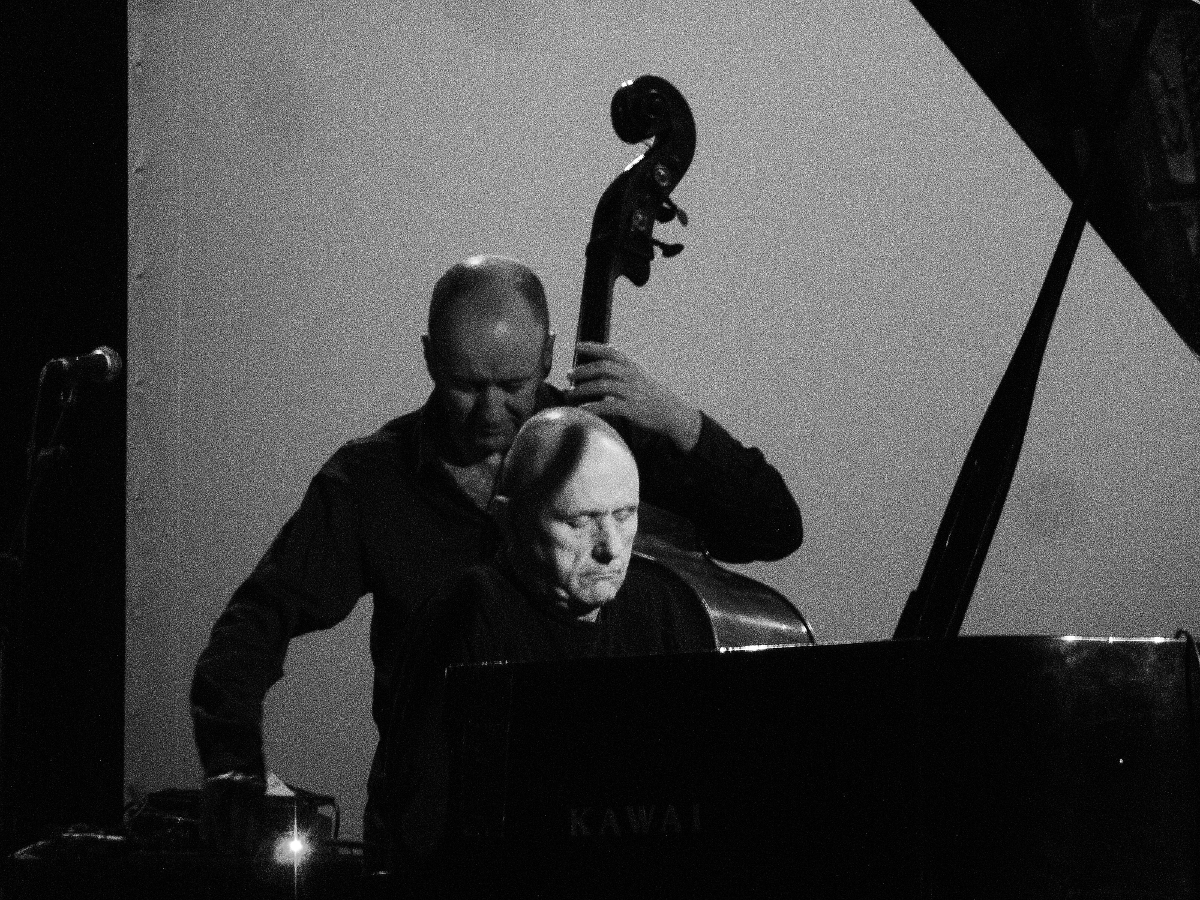

Swanton winces and gurns with pleasure and/or pain as he wrenches subtleties and vibrant tones from his bass. Chris Abrahams is all the while sat before the piano as serenely as the tide his keyboard trills resembles, repeatedly rising and receding but as constant as the perpetual lifeblood swell of the seas.

Swanton winces and gurns with pleasure and/or pain as he wrenches subtleties and vibrant tones from his bass. Chris Abrahams is all the while sat before the piano as serenely as the tide his keyboard trills resembles, repeatedly rising and receding but as constant as the perpetual lifeblood swell of the seas.

Swanton, Buck and Abrahams gradually rise up into a huge, rumbling thrall which engulfs the church from narthex across the nave in an actual cathedral of sound which is almost angelic in its prolonged, ecstatic hold and seeming disavowal of the possibility of release.

But when a conclusion arrives, it does so slowly, in an extended outpouring rather than with a swift explosion or with any sudden activity; The Necks are far too tantric for that, too Zen for taking the easy or obvious path towards the inevitable finale. Rather they follow their own trifold path to the last dying notes together, forging something wholly of itself en route.-Richard Fontenoy-