Cherry Red / MVD Audio / New Ralph Too

It’s been nine months since my last foray into the deep Residential past and, subsequently, I have been sitting quietly, listening intently for the call of the Eskimo. It seems to make perfect sense that it has only now sounded forth with the onset of winter. Sadly, however, for all devotees of the band, that lonely lacuna has recently been punctuated by some truly unwelcome news: the death of Hardy Fox.

When The Beatles play The Residents and The Residents play The Beatles, Hardy Fox can truly be viewed as the John Lennon of Louisiana’s most phenomenal pop combo. Fox had been ill for some period of time, and finally took off the mask in autumn 2017, outing himself publicly as co-founder and primary composer for the band, which he formed alongside fellow Louisiana Tech University graduate Homer Flynn in the late 1960s. The Eyeball Prime subsequently died on 30 October 2018, from brain cancer, at the age of 73.

For anyone who has loved the band, for anyone who was properly, unforgettably and irredeemably skullfucked on first encountering their nightmarish Freudian unconscious writ large, or who chuckled along with their loving yet savage deconstruction of pop music, or who admired in awe their single-minded staking out of a unique territory in modern music, this was another major musical hammer-blow delivered by the Grim Reaper. There may not have been the lavish outpourings of mass public emotion as for David Bowie or Prince, nor airwaves suddenly bursting full of classic back catalogue as with Mark E Smith or Pete Shelley, but make no mistake, when he left the building, Hardy Fox was at that same level. And, if you are going to have lived a life, being the progenitor of The Residents was for sure a Helluva way to do it.So, with a heavy yet appreciative heart, let us nevertheless smile, take up the trail anew, and consider another double-barrelled blast of lunatic flair unleashed our way through the lavish Residents re-release programme.

~

When we last left our heroes, the times they had been a-changing: the punk era and its febrile aftermath had led to a distinct upturn in fortune for The Residents. As the 1970s staggered towards its ragged end, audiences keener for a wider and wilder bill of fare than those at the start of the decade had begun to embrace the band. Indeed, their “Satisfaction” single and Duck Stab album had become, dare one say (one dares, one dares) cult hits.

When we last left our heroes, the times they had been a-changing: the punk era and its febrile aftermath had led to a distinct upturn in fortune for The Residents. As the 1970s staggered towards its ragged end, audiences keener for a wider and wilder bill of fare than those at the start of the decade had begun to embrace the band. Indeed, their “Satisfaction” single and Duck Stab album had become, dare one say (one dares, one dares) cult hits.

The songs that eventually became Eskimo had actually been started as far back as spring 1976, being intended as the follow-up to Fingerprince. However, true to the pattern that we have now established regarding The Residents, such considerations meant nothing. Duck Stab / Buster & Glen had in the end taken that place in the canon, and so Eskimo did not see its release until September of 1979.

Even before one reached the contents of the grooves within, a striking Residential paradigm shift had been embodied on the album’s artwork, Eskimo marking the first appearance of the band in the eyeballs-and-tuxedos outfits that, for many (probably most) fans continues to be their signature visual representation. Standing amidst jagged peaks of black and white ice, the four Residents pose elegantly in white tie, their walking canes at as jaunty an angle as their top hats, each with an outsized human eyeball for a head. It is an utterly perfect piece of costume and visual design – stylish, off-kilter, humorous, anonymous, yet instantly recognisable. Like The Stones’ tongue logo, the eyeball head immediately became the perfect metonym for The Residents.

And then there was the music. The Residents had been intimidating for some time that the shadowy and entirely genuine Bavarian ethno-musicologist N Senada – a “primary source of inspiration” for them – had been spending time in Greenland studying Eskimo culture. Absorbing his pioneering research, the band had worked hard to reproduce a number of key Inuit stories, which Eskimo documented as a pairing of musical ritual and explanatory narrative. Using a battery of lo-tech instrumentation – cheap guitars, primitive Casio keyboards and the like – the band also employed the EMS synthesiser, its exciting and innovative tonalities skilfully employed to conjure the icy overtones of the northern wind.Contemporary stories also told of the band frequently decamping to the Arctic, immersing themselves deeply in the culture of the region and its people, and channelling this faithfully into the music. Of course, they really did this. In fact, so profoundly did The Residents inhabit the music that they would apparently lock members of The Cryptic Corporation out of their recording sessions and only communicate with them via a series of “strange cries”. The album’s master tapes – locked temporarily in a bank vault by Chris Cutler after a bitter severance with The Cryptic Corporation – were even delivered by a courier wearing traditional Inuit dress. As one can see, for The Residents Eskimo was a deeply personal and faithful project of ethno-musicology.

The album begins with “The Walrus Hunt”, whose cold winds slowly give way to the paddling of kayaks as the Inuit hunt the titular blubbery prey across the floating ice packs. A delicate and narcotising melody, its hollow, reedy notes no doubt played on a genuine bone pipe, repeats gently in the background, the unsettling cries of the doomed walrus in absolutely no way reminiscent of a Resident gargling with mouthwash in the studio bathroom.“Birth” is a brutally uncompromising study of female infanticide (sound enticing?), the joy of the Inuit birthing ritual within an ice cave tinged with worry that if the new-born is not male, and thus unable to hunt, it will be killed immediately. From the modern Western perspective this Inuit tradition seems almost unbelievably cruel and murderous yet, ever wary of Malthusian over-population in a harsh and resource-limited environment, it is vital in the unforgiving setting of San Francisco in the Arctic.

“Arctic Hysteria” – or Piblokto to give it the indigenous term – conveys the temporary state of madness induced, mostly in women, by the endless months of Arctic darkness. To summon the untethered mind of the woman back to reality, the men gather and perform an ancient healing song, some of whose syllabic similarities to “chicken shack, hog back, cupcake” are, of course, entirely coincidental. It’s easy to let the vast, freezing darkness play tricks with one’s perception, after all.“The Angry Angakoks” evokes the shaman of the Inuit, their “magic men”. Some friction arises, however, when the tribe suspects that these angakok are proving slow to use their powerful Arctic medicine to free up the hunting grounds from the thick crust of winter ice and facilitate the hunt of the venerated, and invaluable, whale. Confrontation with shaman is ill-advised, though, as the dramatic climax makes abundantly clear.

Most challenging of all, though, is “A Spirit Steals A Child”, a disquieting musical examination of how the Inuit’s youngest are sometimes abducted by The Weeping Seal, a selkie-type being, half-seal, half-human, which preys on young left unattended. The child is only returned after a gruelling spirit battle in which the angakok, now in a slightly more heroic role (though sounding uncannily like Vic Reeves at times), use a dog spirit – present in the decapitated head of an unfortunate canine – to compel the Weeping Seal to comply.

The album closes with the ten-minute odyssey of “The Festival Of Death”, the Inuit celebration of the end to six months of winter and the return of the life-giving sun to the skies. Ritual chanting, rhythmic drumming, hand-clapping and spiritual transcendence are the order of the day here.Disc one closes out with two cold curious: a demo version of Eskimo (which speculation says may have been used to show an increasingly impatient Ralph Records that the band were actually busy recording the album, not merely taking endless trips to the Arctic wilderness in order to imbibe large quantities of psychoactive reindeer urine) and a vocal-only a capella track which allows one to really get to grips with the nuances and complexities of the Inuit’s entirely genuine language.

Indeed, The Residents’ outstanding fieldwork in this area came to be highly influential on leading linguistic theoretician RMW Dixon, persuading him that pre-generative Inuit structuralist traditions emphasized the need to describe each language in its own terms, rather than imposing on individual languages concepts whose primary motivation comes from other languages, in contrast to traditional grammar and many other theoretical frameworks. Honestly, it really did.

Disc Two, or perhaps more appropriately described as Disco Two in this case, contains a golden treasure chest positively overflowing with a bounty of bonus material: the 1980 remix “Diskomo” (choice cuts of the Eskimo material given a nifty disco beat), the EP B-side tracks “Goosebumps” (a collection of children’s Mother Goose songs played on toy instruments), several tracks from the 1983 offcuts compilation Residue, The Residents material from Subterranean Modern (the various artists album issued by Ralph Records which stipulated that each band contribute a version of Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart In San Francisco”, Chrome and MX-80 Sound being other esteemed participants), as well as rehearsal and live versions from the mid- to late Eighties. The final track, “Eskimo Opera Proposal”, makes me long for a production to final take place at La Scala, Milan.Eskimo is a strange, but important, piece in the larger jigsaw puzzle of The Residents’ work – a fully realised concept album, a wry satire on world music before the phenomenon had even been named or achieved any real measure of traction, a camouflaged dig at escalating consumerism and a pinprick in the po-faced discipline of social anthropology. When so many of anthropology’s proponents were either rather easily hoodwinked (from Margaret Mead to Napoleon Chagnon) or downright fraudulent (from Manuel Elizalde and his bogus stone age Tasaday people to Carlos Castaneda’s highly influential yet profoundly non-actual ethnography), the work put forward on Eskimo by The Residents is no less poetically true for being entirely made up a musical interpretation. And, unlike The Residents, neither Mead nor Elizade got to share a table with Donna Summer at the Grammy Awards.

Given The Residents’ fusion of anthropology and disco, there is an especially delicious postscript on this theme, too. One of the main drivers for the popularisation of the disco phenomenon was a 1976 New York Magazine article entitled “Tribal rites of the new Saturday night”, an anthropological essay which explored the then-unknown dance-centred subculture through the lifestyle of one of its central characters, celebrity dancer Vincent. So compelling was the narrative that the essay quickly formed the basis of a fictionalised film version, Saturday Night Fever, featuring John Travolta as Vincent.Like The Sex Pistols on The Grundy Show, Saturday Night Fever lit the blue touch-paper on disco, seeing it explode across the globe into a multi-million selling phenomenon. In 1996, however, the essay’s author – British writer and journalist Nik Cohn – revealed that it was in fact a complete fabrication, based largely on clubgoers he knew in England, with Vincent modelled on a Shepherds Bush mod from the Goldhawk Road. Listening to “Diskomo”, it’s almost like The Residents planned it that way…

~

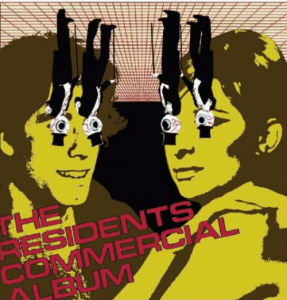

And it is the aforementioned John Travolta who features – in the estimable company of ‘Babs’ Streisand – on the cover of the next Residents re-release, 1980’s The Commercial Album. Against an inverted background of a Tron-style game-grid, the two entertainers have each given their two peepers to form the heads of a couple of Residents, appearing here for a second time in their tuxedo-and-eyeball outfits.

And it is the aforementioned John Travolta who features – in the estimable company of ‘Babs’ Streisand – on the cover of the next Residents re-release, 1980’s The Commercial Album. Against an inverted background of a Tron-style game-grid, the two entertainers have each given their two peepers to form the heads of a couple of Residents, appearing here for a second time in their tuxedo-and-eyeball outfits.

What joy it is to see The Residents splashing it all over, too.

Work on The Commercial Album followed on immediately from the completion of Eskimo, starting in September 1979 and stretching through to the following July, with the album seeing its final release in October 1980. Only a month later, Ronald Reagan would beat the incumbent Jimmy Carter to win the forty-ninth US presidential election, his new administration becoming an energetic precipitant of the insurgent tide of Laffer Curve economics, consumerism and lifestyle choices which came to dominate throughout the Eighties. The Residents’ contemporary focus on the satirisation of commerciality was, pun fully intended, completely on the money.

Ruminating on the nature of commercial pop songs, The Residents’ had begun by asking themselves “What did ABBA and Fleetwood Mac have that they didn’t?” There are probably more possible answers to that question than there are quarks in the San Francisco Bay but, whatever the truth of the matter, The Residents decided to boil down the formula of a successful pop hit into an easy five-line formula, and use it to execute a batch of stripped down, non-repetitive hook-tastic pop smasheroos in order to then compile them onto a single album, their own “compact and portable Top 40.”And what a Top 40 it is, too. Each track is its own perfect miniature Residents symphony, from blockbuster hits such as “Perfect Love” and “The Act Of Being Polite” to long-form pieces such as “When We Were Young” and ‘The Nameless Souls’. What’s so immediately striking about the songs is that, with the Oulipian constraint of a restricted duration firmly in place, they really do showcase how much is possible in one minute. Less, here, really can mean more. Samuel Beckett once said of his erstwhile mentor, “James Joyce was a synthesizer, trying to bring in as much as he could. I am an analyzer, trying to leave out as much as I can”. These pithy bons mots also capture perfectly the difference between the approaches of Eskimo and The Commercial Album, The Residents of the latter channelling their Beckettian mojo to full effect.

And, sprinkling a little magic dust across the pieces, is the array of special guests invited aboard by the band: maestro instrumentalists Fred Frith and Chris Cutler, the incomparable Lene Lovich, XTC’s resident synesthetic genius Andy Partridge, and even (though uncredited), Brian Eno and David Byrne (who had been working on My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts nearby), contributing some keyboards and backing vocals respectively. And, the cherry atop the Bakewell tart, returning in a blaze of glory is Snakefinger (see reviews passim), spreading his writhing, sinuous playing all over the album like buttery guitar smothering hot toast.The Commercial Album is an utterly perfect distillation of everything The Residents had been trying to achieve throughout the Seventies and, as several commentators have noted, provided the perfect coda for this work before the very different decade of the Eighties saw them embark on new kind of dark adventure in the Mole trilogy.

In addition, continuing their traditional running of rings around the mainstream, The Cryptic Corporation purchased forty one-minute radio slots on the airwaves of San Francisco’s leading commercial radio station, KFRC-AM, and proceeded therein to play the album in its entirety. And so, amidst contemporary Billboard blockbusters such as “D.I.S.C.O.” by Ottowan, “Woman In Love” by Barbra Streisand and “Lady” by Kenny “I Just Checked In (to See What Condition My Condition Was In)” Rogers, the ears of SF’s pop pickers were caressed by the new Residents album. All of it. Every delicious mini-pop minute.Billboard themselves, their knowledgeable-but-still-entirely-clueless knickers firmly in a twist, drew spectacularly ill-informed parallels with the cash-for-exposure “Payola” scandal which had so damaged the medium of US radio in the Fifties and even come close to terminating the budding career of later kingpin of US pop Dick Clark (last seen by us dressed in a Nazi uniform and clutching a carrot on the cover of a certain Third Reich ‘n Roll album). Was it ethical, they wailed? Was it legal, decent, honest and truthful? Was it art, or merely advertising? From the offices of The Cryptic Corporation came only a contented silence.

Do I really still have to mention the crammed to the gunwales second disc of bonus material? Oh all right, have it your own way, you churlish lot. Well, it’s all present and correct, stuffed full of alternative versions, rehearsal and live material from the Eighties, and – best of all – a first sighting of several Commercial Album tracks which were reworked for, but not used in, the Icky Flix thirtieth anniversary project of 2001 (which was surely the perfect time for some more Eurostile Extended Bold).~

So, what can we conclude from all this? Well, frankly, that you owe it to yourself to shell out for these two stonewall masterpieces. Both of their time, and transcending it completely, this is, in Winston Churchill’s famous analysis of the career of The Residents, the end of the beginning. Here, the band draw a line under the Seventies and turn to face the brash new world of the Nineteen Eighties. The latter was, after all, the decade that gave us Back To The Future. What more need be said?

Except possibly, Hardy Fox, thanks for the good years.

-David Solomons-