Cherry Red / MVD Audio / New Ralph Too

Twenty minutes into the future. Allow me a short digression:

He’s the toast of the town (lightly buttered). He’s the non-fattening sugar substitute in your tea. He’s a bon vivant, a gaucho amigo, a goomba, a mensch, and the fifth musketeer. He’s the apple of your eye and aren’t you glad he’s here? Direct from a wax and shine at the car-wash around the corner, it’s the man of the hour, or for at least a good thirty minutes…

There was something utterly transfixing about Max Headroom: the solid block of blond hair, the black suit and black tie that never moved an inch; the frantic musculature-defying head movements; the wild, random digital glitching, looping and pitch-shifting of his voice; the easy charm that was a hair’s breadth from sarcasm (or was it the easy sarcasm that was a hair’s breadth from charm?). The non-computer-generated computer-generated talk show hosti was, for a few years, a genuine icon of the 1980s.The origin story of Max’s creation and rise to global fameii is a long and tortuous one – several different types of show, often concurrently, on both sides of the Atlantic, certainly confuses many recollections of who he was and where he came from – but, in the anarchic early years of Channel 4 Television under founding chief executive Jeremy Isaacs, many weird, wonderful and subversive things came bubbling up from between the cracks in the broadcasting pavement. Max’s genesis had actually been as a VJ link man between music videos – still something of a novelty for most viewers in the mid-Eighties – and, during his shows of the era, some truly unforgettable ones were beamed direct into living rooms across the UK, particularly “Goodbye Tonsils” by (then and now) criminally-underrated Australian sample maniacs The Severed Heads, and Storm Thorgeson’s outstanding Get Carter video homage for Intaferon’s pop masterpiece “Get Out of London”.

Yet, even over and above these undoubted highlights, Max showed one short burst of footage that burned itself instantly and indelibly into my teenage brain. Four murky figures moved jerkily around their instruments in a room, completely covered in newspaper (both them and the room), like some kind of current events Klu Klux Klansmen. The grainy black and white visualsiii were accompanied by the most mind-fuckingly nightmarish music that I had ever heard, the kind of thing that attended one’s worst dreams. Of course, I was absolutely hooked.

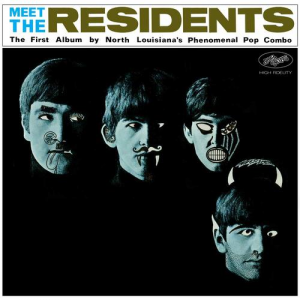

Though I was still reeling in utter incomprehension at what I had just seen, luckily, I was compos mentis enough to commit to memory the photo that Max flashed up briefly – four figures, their eyes glowing bright against their dark, pointed paper cowls, and in the foreground a kick-drum with a skull atop it. And on the kick-drum, scrawled in spidery handwriting, their name… The Residents.Soon after, there followed an increasingly familiar ritual – the train up to town, the tube to Notting Hill, the walk down Portobello to Rough Trade in Talbot Road. With some suitably mentor-like guidance from one of the guys at the counter, the return journey was spent gazing reverentially at the cover of the band’s first album, Meet The Residents.

*

Meet The Residents, pressed in an edition of 1,050 and released on April Fool’s Day 1974, was the culmination of several years of feverish creative activity which followed the embryonic band’s relocation from Louisiana to San Francisco at the end of the Sixties. (At least) two full length “tape albums” had in fact preceded it: The Warner Brothers Album and Baby Sex, the former, according to Residents’ legend, gifting the band its name when the label returned it unwanted to the band at their then-address in San Mateo.

Meet The Residents, pressed in an edition of 1,050 and released on April Fool’s Day 1974, was the culmination of several years of feverish creative activity which followed the embryonic band’s relocation from Louisiana to San Francisco at the end of the Sixties. (At least) two full length “tape albums” had in fact preceded it: The Warner Brothers Album and Baby Sex, the former, according to Residents’ legend, gifting the band its name when the label returned it unwanted to the band at their then-address in San Mateo.

It was, however, at their later address, a self-created live / work space in a former printworks on Sycamore Street (on the border between The Castro and the Mission District), that the band recorded much of what appeared on the album, as well as working on their abandoned-and-resurrected film (Whatever Happened to) / Vileness Fats?

In the forty plus years since the album’s “release” (with little in the way of independent label infrastructure existing in the mid-1970s, just getting the album into record stores was a major administrative and logistical challenge), “popular music” has seen all major of avant-garde, experimental and otherwise outsider influences absorbed into its ever-protean body; Daniel Johnson can be seen on T-shirts worn on the high street; Jandek can perform at sold-out music festivals; Hell, even Fred Lane is allegedly releasing a new album sometime soon. Yet when Meet The Residents hit the racks, there was almost no framework of reference for what the band were doing.A couple of hundred miles down the state, another adopted Californian, the young David Lynch, was beavering away on his own startling labour of love début, Eraserhead. Aesthetically, the two artworks have much in common: their fiercely creative and independent vision, their transcendence of any budgetary or technological limitations inherent in their creation, their complete singularity. Despite limited critical or popular attention at the point of release, both have, in their own respective fields, proved hugely influential on those that came later – yet, both inhabit their own completely unique space, a branch of evolution which was effectively created with them and which only they could fill. There is really precious little that Pete Frame could do with The Residents.

And just as no film will ever look like Eraserhead, no album will ever sound like Meet The Residents. Right from the nightmare nursery rhyme cover of Nancy Sinatra’s “These Boots Are Made For Walking” that opens the set, the sense of wandering through a completely alien musical landscape is unrelenting: sudden bursts of noise and static erupt like over-ripe fruit, sing-song voices waiver uncertainly between reassuring and threatening, instruments and found sounds congeal into uneasy blobs. If there could be any kind of analogue, it might be Alice in Wonderland, where dream logic turns on a sixpence between humour and violence, and it is never entirely clear who is friend and who is foe.“Guylum Bardot” is like some stylish nightclub lament gone to Hell. “Smelly Tongues” rattles your brain like a virus. “Skratz” is, I imagine, the music that plays in your head when you are drowning. “Infant Tango” could almost – almost – be on one of those The Sound of Angola ‘72 compilations bringing together insanely funky homemade African recordings of the 1970s. My personal favourite, “Breath And Length” is the sound you get when you put dogs in charge of a recording.

What more could you possibly want? Or need? Or handle? I guess the answer is “the inclusion of masses of bonus material”, featuring mono and stereo mixes, the 1972 proto-Residents Santa Dog EPiv which preceded the album, as well as a veritable cornucopia of draft versions, oddities, miscellanea and live renderings.There is no record collection – nay, scratch that, this is 2018 after all (get with the digital format revolution, granddad!) – there is no music collection, anywhere in the world, which can consider itself complete or mature without a copy of Meet The Residents.v

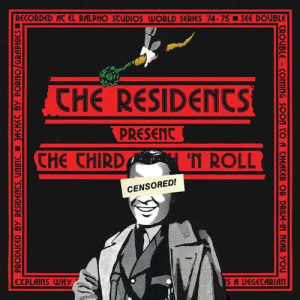

The band’s second album, at least in terms of chronological releasevi, is, if anything, even more unnerving that their first. Given the musical direction contained within the grooves of Meet The Residents, it’s hard to imagine where any other band might have thought they could go next. The Residents, though, being The Residents, and most decidedly not any other band, decided that the answer was clear: an homage and satire of the pop music and commercials of Sixties, all wrapped up within parodic Nazi iconography. You really couldn’t make it up.

The band’s second album, at least in terms of chronological releasevi, is, if anything, even more unnerving that their first. Given the musical direction contained within the grooves of Meet The Residents, it’s hard to imagine where any other band might have thought they could go next. The Residents, though, being The Residents, and most decidedly not any other band, decided that the answer was clear: an homage and satire of the pop music and commercials of Sixties, all wrapped up within parodic Nazi iconography. You really couldn’t make it up.

Released in February 1976, Third Reich’n’Roll is truly a bounty of Residential weirdness, from its arresting cover – a dense block of black featuring American media icon Dick Clark dressed in an SS uniform and clutching a carrot whilst several cross-dressing Hitlers dance on clouds behind him, all bounded within a repeating red Third Reich’n’Roll hakenkreuz bordervii – to its two tracks,viii each an entire side in length, and comprising fused, spliced, overdubbed and distorted mash-ups of classic rock songs, with added voices, instrumentation and tape sounds. Many of the originals are instantly recognisable, whilst others are distorted almost beyond the point of identifiability, collapsing under the weight of their semi-phonetic reinterpretation. Some of the songs are actually played simultaneously.

Famously (!), the band employed a novel musical methodology to achieve all this: putting on a record, jamming along in their own unforgettable way, then finally removing the original to leave only the entirely new and bizarre performance. Much amusement is to be had spotting the original compositions buried within the rubble, some relatively mainstream, others less so: “Horse With No Name”, “The Letter”, “Psychotic Reaction”, “Telstar”, “96 Tears”, “Light My Fire”… oh, I could go on and on. But here I am spoiling all the fun for you. Sorry about that.Long-standing Resident-watchers often position Third Reich’n’Roll as a unique juncture in the band’s canon, seeing it as their first real concept album and as a turning point, after which their subsequent releases became thematically more sophisticated and methodical. In addition, not content with ripping up the musical rulebook – or more accurately ripping up even further the already ripped up rulebook they ripped up with Meet The Residents – the band recycled sets and resources from their stalled Vileness Fats film project, shooting a promotional film to accompany the album. It was a snippet of this film which appeared on Max Headroom’s show almost a decade later (and which can thus rightfully claim at least one convert). Many, including the Museum of Modern Art, make the claim for this film being the first ever music video. Patently ludicrous one may think, but in reality no more so than the claims for Queen‘s “Bohemian Rhapsody” made some eighteen months later.ix That, though, is perhaps getting too serious about an album on which, more than any other, The Residents sound as though they are having a really good time.

As with Meet The Residents, this two-disc re-release comes groaning under the weight of tasty extras. There are numerous live recordings (including the 1976 “Oh Mummy” show which marked the band’s first return to live performance for some years) and, best of all, a truly awe-inspiring six-part suite entitled “German Slide Music”, supposedly recorded in July 1975, in-between the two original Third Reich’n’Roll tracks. Top tip – give a music-head friend a blind taste test of Parts 5 and 6 and see what they make of them.Overall, I’m not sure that Dietrich Eckart would have approved, but National Socialism never sounded this good.

*

On 22 November 1987, a deranged prankster wearing a Max Headroom rubber mask and standing in front of a wobbly homemade background managed twice to hijack the television broadcasts of WTTW Channel 11 Chicago in what became known as the “Max Headroom broadcast signal intrusion”. For the second of the two pirate attacks:

The picture suddenly cuts over to a shot of the man’s lower torso. His buttocks were partly exposed, and he was holding the now-removed mask up to the camera with the rubber extension now placed in the mouth of the mask, howling, “They’re coming to get me!” An unidentified female accomplice wearing a costume then told him to “bend over, bitch.” The accomplice then started to spank the man with a flyswatter as the man screamed loudly, shouting “Oh do it!” part way. The transmission then blacked out for a few seconds before resuming the Doctor Who episode in progress [‘The Horror of Fang Rock’]; the hijack lasted for about 90 seconds.

Anonymous, masked Dadaists making unsettling intrusions into the reality fabric of unsuspecting viewers. Sounds like someone we know.

-David Solomons-

i In 1985, the computer-animation of the period was light years away from being able to realise the original creative vision of Max. Instead, a simulation of a computer-generated host was cleverly pieced together through plaster of Paris prosthetic make-up, a two-piece fibreglass suit and background of hand-drawn cell animation copied from a chocolate milk advertisement.

ii As an exemplar of Max’s universal profile, in April 1987 he was even on the cover of Newsweek magazine, his familiar wide-mouthed, cackling bust clad in white tuxedo and Wayfarer shades next to the by-line “Mad About Max, The Making of a Video Cult”.

iii Residents lore relates that, to film it, the band purchased a stock of – at the time – unbelievably costly colour video, only to then use it to film sets that had been created entirely in monochrome. Now that’s panache.

iv “…four carefree blasts of… something”

v It will nestle perfectly alongside Material Girl: The Best of Madonna’ or Dark Magus, or The Best of Klaus Wunderlich or Yeezus or Crepitating Bowel Erosion. Just not that horrid :zoviet*france: one with the roofing shingle sleeve.

vi The band’s second recorded album was actually Not Available, created in late 1974 after the release of Meet The Residents, yet not actually released until 1978. According to the Theory of Obscurity promulgated by the band’s (perhaps fictional) collaborator, the legendary Bavarian avant-gardist N Sendada, the album was to be locked away until the band had completely forgotten about it, that being the key prerequisite for its actual release.

vii Perhaps unsurprisingly, the album in its original release form was banned in Germany.

viii The first track, “Swastikas On Parade” was supposedly recorded during a singe hectic week in October 1974, and the second, “Hitler Was A Vegetarian”, a year later in October 1975.

ix The promotional film for “Strawberry Fields Forever”, made so that The Beatles could promote the single without the need for incessant and distracting personal appearance on television, was shot at the start of 1967, after all. Of course, despite furious claim and counter-claim, it was never proven that The Beatles were not The Residents…