Cherry Red / MVD Entertainment / New Ralph Too

In Early Modern English – the transitional phase of the English language from the Middle English of the late fifteenth century to the Modern English of the mid to late seventeenth century – the mole was known as the “mouldywarp”. Could there be any more Resident-like a term for anything than a mouldywarp? Indeed, there could not; moles were made for The Residents right from the get-go.

In Early Modern English – the transitional phase of the English language from the Middle English of the late fifteenth century to the Modern English of the mid to late seventeenth century – the mole was known as the “mouldywarp”. Could there be any more Resident-like a term for anything than a mouldywarp? Indeed, there could not; moles were made for The Residents right from the get-go.

Added to which, the furry, fossorial little blighters have often been associated with outré music due to their handy metaphorical value in respect of the associate term “underground”. Even wider afield than music, in dream interpretation, moles symbolise unconscious forces or influences, those occurring “beneath the surface” which cannot be perceived but which are nevertheless highly impactful. And when The Residents got their musical hands on moles, they were indeed to prove highly impactful.

~

When we last left our heroes, they had just entered the 1980s with the elegant satire of The Commercial Album. Despite the fact that punk and new wave had – in the main – proved beneficial to The Residents’ career, The Commercial Album did not garner quite the level of critical approval for which the band might have hoped. In typically Residential style, however, the band decided that such a failure was not nearly large enough, and that their next project should be a truly prodigious failure, a colossal disaster impossible to ignore or gloss over.

And so, they began work on a truly monumental multi-part saga recounting the devastating consequences wrought by some vague form of ecological catastrophe and the resultant social, cultural, political and, at times even physical, battle between the Moles and the Chubs, two opposing peoples affected by it. Being a work on such a scale, the band’s original vision was that the Mole saga should be released as a trilogy. Or possibly a hextology (three albums covering the full narrative of the trilogy, with another three albums focusing on the music of the fictional Mole and Chub cultures). Of course, it actually turned out to be a tetralogy: parts one and two (The Mark Of The Mole and The Tunes Of Two Cities) were released in the consecutive years of 1981 and 1982, with part four (The Big Bubble: Part Four Of The Mole Trilogy) following on a few years later in 1985. Parts three, five and six, if indeed they were ever completed, remain locked away somewhere in the Residential archive. Right. Got that? From the standpoint of their audience, The Mark Of The Mole, and The Mole Trilogy in general, is often seen as the most divisive work in the band’s catalogue. It is relentlessly dark and oppressive, an allegory of racial intolerance and bigotry with all the lack of joy that probably entails, an “operatic, avant-rock adaptation of John Steinbeck‘s Grapes Of Wrath“, as some have put it. Even its biggest fans agree that it probably represents the least accessible set of recordings in the band’s entire oeuvre.i

From the standpoint of their audience, The Mark Of The Mole, and The Mole Trilogy in general, is often seen as the most divisive work in the band’s catalogue. It is relentlessly dark and oppressive, an allegory of racial intolerance and bigotry with all the lack of joy that probably entails, an “operatic, avant-rock adaptation of John Steinbeck‘s Grapes Of Wrath“, as some have put it. Even its biggest fans agree that it probably represents the least accessible set of recordings in the band’s entire oeuvre.i

For all these reasons many fans adore it, and an equal number struggle with it.

~

No examination of The Mole Trilogy is really possible without at least some exegesis of the epic story that undergirds the whole madcap affair. Its ominous opening features a radio weather report (narrated by the estimable magician, actor and musician Penn Jillette), which warns of volatile storm conditions likely to set in over the central lands, those containing the tunnels of the Mohelmot people. The Mohelmot are a subterranean race whose preference for life beneath the surface earns them the moniker “Moles”. The storm soon arrives with Biblical force, quickly flooding the Moles out of their underground dwellings, and forcing them into a desert migration towards the sea, where dwell the coastal Chubs. The Chubs are a somewhat fat, slothful people who live for pleasure and instant gratification in a bloated and complacent society.

Initially, the Chubs embrace the arriving Moles, seeing them as an abundant and exploitable source of cheap labour. Despite the potential economic advantages, however, the hard-working Moles soon alienate the Chubs, who begin to complain both about miscegenation and the rising trend of Moles displacing Chubs from the best jobs. (Is any of this sounding familiar yet?) These simmering interracial tensions erupt when the Chubs create a “New Machine” to eliminate the need for low-skill manual labour altogether,ii offending the Moles (whose strong work ethic is driven by their religious beliefs). A short war breaks out, but ultimately ends with a stalemate and no clear victor. At the armistice, the situation calms to an uneasy peace in which the two ethnic groups continue to live together uncomfortably for at least another generation.Musically, The Mark Of The Mole (part one, released in September 1981) is a challenging mix of drones, synthesisers, electronic sounds and chanted vocals. The new sounds of the era are immediately apparent, but there are also plenty of familiar Residents tropes: the nursery rhyme arrangements, the distinctive use of voice, the ever so slightly off-key melodies. Moments of “The Ultimate Disaster” veer into sudden savage near-industrial noise. Parts of “Another Land”, with a more mainstream vocal, could almost qualify as synth pop. “The New Machine”, again, borders on what would later come to be known as industrial, yet could somehow never be anything else other than Residents material. “The Final Confrontation” has elements of Harry Partch audible in its spindly structure, together with some textures redolent of classic 1950s sci-fi (for example Louis and Bebe Barron’s evergreen score to Forbidden Planet).

Particularly in this first part of the saga, the dark and dour flavour of the Mark Of The Mole sound polarises in equal measure, some liking its bleak and cheerless textures, others lamenting the missing elements of humour and lightness of touch which had always leavened The Residents’ previous work. The first disc then concludes with alternate “Live In The Studio” versions of each track.The Mole period also marked the point at which the home-made cut and paste Residents sound of the 1970s was replaced by a smoother and more advanced one, fuelled by the blossoming new technological possibilities of the digital 1980s, synths, samplers, et al. As with any such radical disjuncture in the work of a beloved band, this was always going to prove contentious. The lo-fi garage band aesthetic of the 1970s was over for good, and The Residents thereafter would be – sonically, at least – a slightly different proposition.

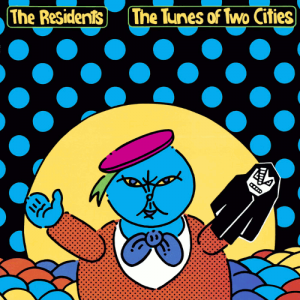

Disc 2, The Tunes Of Two Cities’ (part two, released in March 1982), adds depth rather than breadth to the Mole saga: eschewing any further narrative, instead focussing on the cultural disparities between the Moles and the Chubs through an examination of their respective musical traditions. Even by The Residents’ standards, this is an out-there idea, and the results exceed even that: the Moles favouring dark, industrial ambient, whilst the Chubs seem to have a yen for light cocktail jazz and electro pop. To get themselves into the groove for the Chub compositions, a spokesResident later explained that they had spent time listening to the greats of the genre: Charles Mingus, Sun Ra and Stan Kenton. Nice.

Opening with the gorgeous “Serenade For Missy” (Residents that your grandmother might like), by immediate contrast second track “A Maze Of Jigsaws” is a truly unnerving piece, coming on like the Third Ear Band and departing like Coil. We then alternate between these polarities, from the extraordinary “Smack Your Lips (Clap Your Teeth)” and the percussive “Mourning The Dead” to the carousel music of “Open Up” and the jazz-on-Mars of “Scent Of Mint”.The Tunes of Two Cities represented an early appearance of the hugely popular Emulator sampler – a key component of Michael Jackson’s era-defining “Thriller” – and in these complex tapestries of sound, the cut-and-splice is noticeably way slicker than The Residents of the previous decade. Indeed, given that The Residents received only the fifth Emulator ever to roll off the production line, they here placed themselves at the very vanguard of the technology that would come to define the 1980s musically. Disc 2 then closes with studio rehearsal and studio live versions of the seven of the tracks.

In any normal sequence, 1983 might have seen the release of part three of the Mole saga. This being The Residents, of course, no such tediously predictable trajectory was ever likely to be followed. Instead, adding a second Emulator to allow full mastery of the musical intricacies of the two recent albums, the band took their Mole mythos out onto the road for a truly mammoth live tour.The Mole Show, with Penn Jillette taking the role of Master of ceremonies, Kathleen French handling the choreography and Phil Perkins designing the lighting, saw the band in variety of old and new costumes performing behind a burlap scrim flanked by huge 21 x 18 foot backdrops, whilst in the foreground actor and dancers performed and stage hands in Groucho Marx glasses manipulated cut-outs of the main characters in order to help explain the narrative.

Jillette would appear onstage as narrator, providing linking segments to further convey the storyline of the performance, and the band also composed additional music to feature during the pre-show, intermission, and after-show periods.iii Perkins’ stark lighting illuminated the stage with a single spotlight, trained on Jillette, who, between numbers, would explain what was happening to the audience, usually in an intentionally patronising and insulting manner. He would also tell long and rambling stories to further baffled and irritate them. Anticipating the successful stage production The Play That Goes Wrong by over three decades, the live Mole Show was deliberately designed to fall apart as it progressed: Jillette pretended to grow angrier with the crowd, criticising the show as its lighting effects and music became increasingly chaotic, the whole screwball enterprise building up to the point where Jillette would be dragged forcibly off stage only to then be returned, handcuffed to a wheelchair and wearing Groucho glasses, in order to deliver his closing monologue. One is bound to ask, “What could possibly go wrong?”

Anticipating the successful stage production The Play That Goes Wrong by over three decades, the live Mole Show was deliberately designed to fall apart as it progressed: Jillette pretended to grow angrier with the crowd, criticising the show as its lighting effects and music became increasingly chaotic, the whole screwball enterprise building up to the point where Jillette would be dragged forcibly off stage only to then be returned, handcuffed to a wheelchair and wearing Groucho glasses, in order to deliver his closing monologue. One is bound to ask, “What could possibly go wrong?”

The answer was to be found in the execution. After a small-scale Santa Monica début in April 1982 (at which only the music was played) in order to properly test the Emulators under “battlefield conditions”, there followed in October a run of five shows in San Francisco, Los Angeles and Pasadena which, despite the bizarre nature of the whole endeavour, seemed to be very well received. There were a few technical gremlins to deal with in the form of the tendency of the band’s first-generation Emulators to overheat but, in general, confidence in the show was high after these initial excursions.

However, just as the band were preparing to take the show to Europe in May 1983, things start to unravel. Two key members of The Cryptic Corporation departed, taking valuable nous and resources with them. The band also found that the enormous size of the Mole Show sets meant that the only plane capable of transporting them was the Boeing 747, instantly spiralling the costs of the tour upwards. With nearly twenty people involved the show, the initial costings had been high to begin with, and to cover it The Residents had made the decision to sell the merchandising rights in advance for $10,000. During the tour, the merchandise sold extremely well, generating far more money than the band made from the tour alone. With the economics out of alignment in this way, it fundamentally compromised the tour’s ability to pay for itself.In and of themselves, the shows in Europe – thirty dates across Germany, Austria, Belgium, France, Holland, Italy, Spain and the UK – went extremely well, garnering critical and audience approval, marred only by the occasional mishap which is in the nature of all such ventures. Jillette, for example, ended up in hospital in Spain (when the stage manager duly had to deputise for him) and was also attacked at one show by an irate audience member who pounced on him when he was tied to his wheelchair.

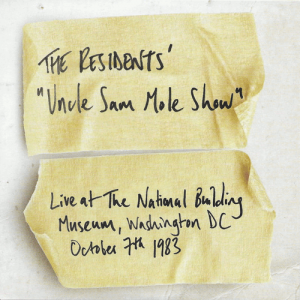

Yet by the time of the final show at Leicester Polytechnic on 1 July, a financial chasm was already opening up beneath the band. The Mole Show had haemorrhaged so much money that Ralph Records was on the edge of bankruptcy. Compounding this monetary misery still further, the band’s tour manager had not paid the British shipping agent, who was holding all of their sets and instruments in England in lieu of payment for their return, a balance well over £10,000. Some quick negotiation did yield a compromise in which The Residents convinced the shipping agent to take a sizeable payment up front, with the balance to follow afterwards, but he seemingly backtracked on this arrangement later, keeping the gear until the entire account was settled.Weary to their very bones, the band were thus understandably unreceptive to an initial offer to perform The Mole Show as the opening section of Washington DC’s New Music America Festival, yet eventually decided that, given their parlous financial state, the money simply couldn’t be passed up. With all their sets and musical equipment still impounded in the UK, the band were forced to cobble together new stage sets and crew from scratch, and also to beg, borrow and steal the necessary Emulator technology on which the complicated and demanding Mole music relied.

That they indeed managed to do so was a triumph in itself.iv That The Uncle Sam Mole Show – as it was known – was considered the highlight of the entire tour was doubly so. As their erstwhile correspondent Frank Zappa would doubtless have underscored to them, necessity was in this case the mother of invention. Never before released, the performance on 7 October is captured in The Mole Box as Disc 5, comprising twenty-two pieces, and what a treat it is.Dim the lights and listen through in its entirety as The Residents’ Mole madness reaches its absolute apogee. There are some little intermission gems and live dialogue snippets (“The Singing Resident Needs Something”), as well as an absolutely apocalyptic version of their signature version of “Satisfaction”. And which US patriot could fail to have their heart stirred by the band’s wonky rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner”?

Disc 4, by contrast, presents concert material from The Mole Show as performed at The Roxy in Los Angeles a year earlier (at the end of October 1982), six months or so before the band embarked for the European leg. In light of the logistically, financially and emotionally chaotic twelve months that separate the two performances, it’s interesting to compare the two: the well-drilled clarity and high-gloss sheen of LA against the raw but inspired performance in Washington.

The lessons of the live Mole Show were in the main bitter ones for the band. The tour had been “chaotic on a scale no one was eager to repeat” and its aspirations, through laudable artistically, had nevertheless brought the entire Residents edifice to the brink of financial collapse. The band were in all seriousness contemplating the end of live performance, and continuation of the whole ambitious Mole saga was brought into question. Indeed, the next release by the band would be 1984’s non-Mole George And James, part of their American Composer Series, comprising covers of George Gershwin and James Brown material. It was not until 1985 that the band would return to anything Mole-related. Disc 3, The Big Bubble (part four, released in 1985) returns to the theme of socio-cultural expansion of the saga, briefly summarising the narrative of the missing part three, and presenting a suite of songs by a fictional band called The Big Bubble. As outlined in the sleeve notes, the errant part three would have re-joined the saga some decades after the original events of Mark Of The Mole, with the Moles and the Chubs still balanced in their uneasy impasse. Miscegenation between the two groups, though, has led to the formation of a traditionalist “Mole purity” movement, the Zinkenites, who want to return the Moles to values of their original culture, Mohelmot (despite the fact that one of the main Zinkenite leaders is himself a cross-breed named Kula Bocca).

Disc 3, The Big Bubble (part four, released in 1985) returns to the theme of socio-cultural expansion of the saga, briefly summarising the narrative of the missing part three, and presenting a suite of songs by a fictional band called The Big Bubble. As outlined in the sleeve notes, the errant part three would have re-joined the saga some decades after the original events of Mark Of The Mole, with the Moles and the Chubs still balanced in their uneasy impasse. Miscegenation between the two groups, though, has led to the formation of a traditionalist “Mole purity” movement, the Zinkenites, who want to return the Moles to values of their original culture, Mohelmot (despite the fact that one of the main Zinkenite leaders is himself a cross-breed named Kula Bocca).

The material itself is something of a hybrid, a synthesis of the Mole and Chub musics explored previously on The Tunes Of Two Cities, but here performed using traditional rock instrumentation. From opener “Sorry” (in which the ghosts of Jandek and Derek Bailey jam together in a basement), to “Stay-Die-Go” with its intrusion of moments of epic Ennio Morricone-esque Once Upon A Time In The West grandeur and the convulsive funk of the titular “The Big Bubble”, the album is – despite the more orthodox instruments in use – perhaps the strangest entry in the entire Mole canon.

Why? It’s hard to say. There is an old aphorism (attributed naturally to Oscar Wilde) that runs “Give a man and mask, and he’ll tell the truth”, and there is a peculiar feeling shot through the grooves that under the guise of The Big Bubble, a side of The Residents occasionally creeps out which gives a glimpse, just the most momentary and fleeting of glimpses, of a different Residents. “Kula Bocco Says So” is perhaps illustrative of this – buried beneath the faux-indigenous chanting and Tiki title are the bones of a serious piece of modern composition. Now maybe the idea of “serious Residents” is an oxymoron, the very notion being antithetical to everything they tried to be and to do, but it’s an intriguing one nonetheless. Like seeing Marilyn Monroe in a black wig, it’s both unsettling and intriguing, a fracture of normality which allows the shadow outline of alternative possibilities to creep through. The disc closes with a number of demo and live versions. Disc 6, Miscellaneous Mole Box Materials, the final one in the set, presents “a selection of recordings which may or may not comprise part of the legendary, unreleased Part Three of the trilogy.” So here we have a six-CD box set of the Mole saga, comprising hours and hours’ worth of material, yet which still manages to hint at ambiguous lacunae and further material secreted away elsewhere. What could be more Residents than that?

Disc 6, Miscellaneous Mole Box Materials, the final one in the set, presents “a selection of recordings which may or may not comprise part of the legendary, unreleased Part Three of the trilogy.” So here we have a six-CD box set of the Mole saga, comprising hours and hours’ worth of material, yet which still manages to hint at ambiguous lacunae and further material secreted away elsewhere. What could be more Residents than that?

And there is some truly first-rate material on this concluding selection of cuts. From doomy instrumental “Lights Out (Prelude)” (why did no forward-looking sci-fi director ever commission a score from the band?) to devotional “A New Hymn” (The Residents get the drop on the modern trend of post-Jóhann Jóhannsson spiritual composition by about thirty years) to the brief, intimate bad dream of “From MOM1”, and topped off, naturally, by a short selection of live tracks, this disc is perhaps my pick of the bunch. A grab-bag of assortments and miscellanea to be sure, but isn’t that always one of the true joys of The Residents?

~

This voluminous – but of course not completely comprehensive – box set is surely the penultimate word in the Mole saga, a project which somehow managed to be simultaneously both The Residents’ Woodstock and their Altamont. A myth (the Mole-Chub narrative) within a myth (The Residents themselves), from almost four decades away much of the truth of the matter is now disguised by a thick cloak of improbability, hagiography and hindsight bias.What we can say is that over a decade into their career, the band decided to reinvent themselves and undertake a spectacularly ambitious artistic project which again, managed to both succeed gloriously and fail spectacularly at the same time. If this isn’t a masterpiece, it’ll do until one comes along.

-David Solomons-

i That, however, did not stop someone making a video game out of it for the nascent and booming Atari market. Oh yes. See its full lunatic glory here.

ii Google self-driving vehicles anyone…?

iii This music was later itself compiled as the Intermission EP.

iv Of course, as predicted by Sod’s Law, the band’s impounded equipment showed up mere hours before the band were due on stage. The costumes and sets from The Mole Show later became part of the permanent collection at the Los Angeles Museum Of Contemporary Art.