Cherry Red / MVD Audio / New Ralph Too

When we last left our heroes in the early 1980s, they had just staggered bloodied but unbowed from the triumphant disaster that was The Mole Show, an interlinked series of albums and associated live tours that detailed the epic and deranged saga of the conflict between two opposing peoples, the Moles and the Chubbs. It would therefore make sense, would it not, to move on to their next release, George & James, which was the start of their abortive American Composer series, unveiled in 1984? But, of course, this is The Residents. Here, chronologies, discographies, release schedules and linear narratives mean nothing.

When we last left our heroes in the early 1980s, they had just staggered bloodied but unbowed from the triumphant disaster that was The Mole Show, an interlinked series of albums and associated live tours that detailed the epic and deranged saga of the conflict between two opposing peoples, the Moles and the Chubbs. It would therefore make sense, would it not, to move on to their next release, George & James, which was the start of their abortive American Composer series, unveiled in 1984? But, of course, this is The Residents. Here, chronologies, discographies, release schedules and linear narratives mean nothing.

Like floating in zero gravity, normal environmental forces are suspended, up and down cease to have any real meaning, and it becomes very difficult to urinate easily. Well, not perhaps the last part but, instead of preceding on to 1984, we must return to 1978. Or possibly 1974. It’s not entirely clear. And there we must finally engage properly with The Residents’ enigmatic mentor, Bavarian composer and music theorist N Senada. Who may in fact be Harry Partch. Or possibly Captain Beefheart. Or who may never have actually existed at all. Right, got that? For in Residents lore, no other album across their vast canon is more mythic, more preposterous, nor more totemic of the band than Not Available.

Shortly after the release of their incredible debut, Meet The Residents in 1974, the band returned to their Sycamore Street studio to work on a next tranche of music. Their approach to these sessions, however, differed significantly from those for the first album, in that they were underpinned by music theory taught to the band by their mentor and collaborator N Senada. Born in Bavaria in 1903, Senada had eventually relocated to California, where he pursued his highly idiosyncratic composition, meeting and working with The Residents in their very early pre-release days.

Sifting through the historical evidence, though, for my money N Senada was as real as Harry Steele, and although the tangible fruits of his collaboration were few, his theories were nevertheless profoundly influential on the band, none more so than his Theory of Obscurity which shaped the entire recording and release of Not Available. This theory stated that an artist could only produce pure art when the expectations and influences of the outside world were not taken into account. In short, instead of recording music with the aim of its immediate release – which may introduce unconscious bias and self-censorship driven by unvoiced hopes of commercial optimisation – music should be recorded in an unencumbered creative flow, left until its creator has almost forgotten its existence, and only then provided with a public release.

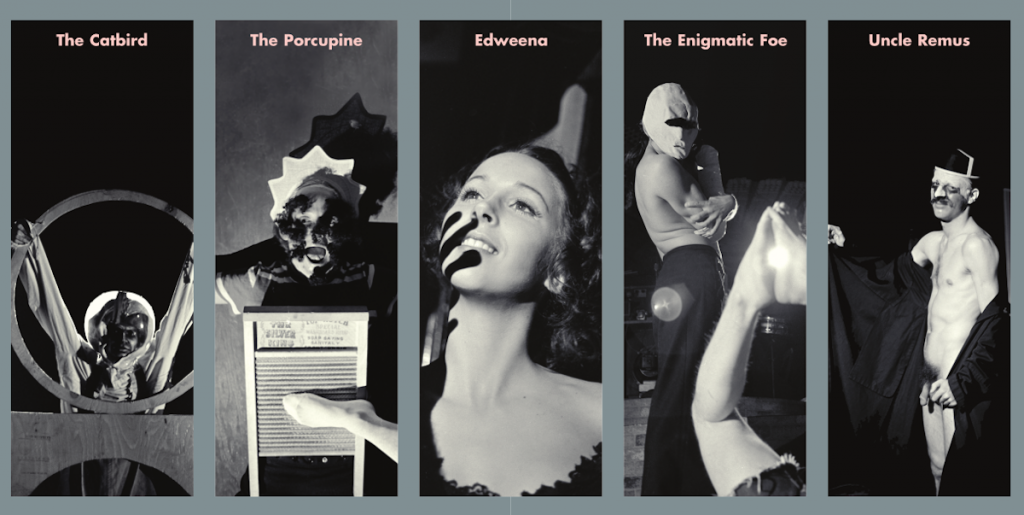

And so The Residents began their recording unfettered by the need to think in commercial terms, and were thus completely free to follow their collective muse wherever it may lead. What they were not free from, however, was the resulting strain of several years of intense “togetherness” in their shared living and working space. Even without a tyrannical overlord of the Beefheart type to put them in a barrel and administer lashings both verbal and physical, the normal tensions of quotidian life could not be repressed for long, especially when compounded by – allegedly – that oldest of sources of discontent, a love triangle. The prospect of considering The Residents’ love lives is to be sure a strange one.Whatever the truth of the matter, it does seem that the band did the sensible thing and channelled it into the music, emerging at the end of the process with multi-part operetta concerning the fraught and tangled emotional relationships between a cast of typically obscure Residential characters: Edweena, her vying suitors Porcupine and Catbird, Uncle Remus and the aptly-named Enigmatic Foe. But of course.

Musically, the album is a delight for Residents fans, mixing the madcap sense of musical adventure and innovation that characterised the band in their early days with a noticeable improved clarity and set of production values. Opener “Part One: Edweena” fuses primitive drum machine and strong melody with the signature Residents off-key phrasing, much I would expect Shuggie Otis to have written if he had been given a heavy dose of Thorazine and confined to an institution. It’s actually a very compelling and rather moving song, one which indeed might have sat comfortably on the soundtrack to an early ‘Beat’ Takeshi movie.“Part Two: The Making Of A Soul”, with its mournful sax and strong rhythmic propulsion, starts out like Roxy Music’s dark twin before cycling through several moods from solo piano melancholic to a jaunty waltz, whilst “Part Three: Ship’s A’going Down” is recognisably Residential bonkersness, a Greek chorus of delirious voices (supposedly the only track ever recorded by the band on which all fours members sing concurrently), though one that closes out with a rather lovely and bluesy sax ending. “Part Four: Never Known Questions” contains some of the best (backing) vocals found anywhere in the band’s canon, with a short two and half minute “Epilogue” taking up the opener’s refrain and summing up.

Disc One also contains two fine versions of “Ship’s A’going Down”, both in the studio in 1982 and live in 1984, together with a live “Mourning Glories” from the 2014 Shadowlands tour, its delicate strings given a particularly fine and sensitive treatment. And lo, in autumn 1978, did Not Available finally… become available. Following the rapturous reception received by the “Satisfaction” single in a Europe still intoxicated by the aftermath of the punk explosion, the Cryptic Corporation were understandably keen for some new Residents material to capitalise on this. However, with endless blubbery delays to the official release of what would be the band’s next album, Eskimo, the Cryptic Corporation were forced to resort to their usual dastardly tricks, and raid whatever was available in the vaults at the time. And I think you all know what they found there. Yes, the post-Meet The Residents material buried there by the band according to Herr Senada’s Theory of Obscurity.Issued in October of 1978, Not Available may or may not have been ready to be dusted off and dragged kicking and screaming into the light of day, may or may not have revealed the band’s deep psychological scars from four years previously, and may or may not have caused Senada to rotate quietly in his casket; but its delicate melodies and atmosphere of quiet melancholy quickly established it as a fan favourite. As many commentators have noted over the years, it is at the same time both very different to Residents’ other releases and yet simultaneously the one that is perhaps most uniquely them.

Being’s as this is the two-CD treasure trove we’ve come to expect as part of the pREServed series, not only do we get the finished item, Not Available, but also the entire (? – nothing about The Residents is ever entirely entire) clutch of demo, rough and prototype recordings made in the aftermath of Meet The Residents, and which were reworked as Not Available and as parts of Third Reich ‘N Roll and Fingerprince, and “incorporated material occasionally proposed as a possible soundtrack for the Vileness Fats film.” Given the provisional title X Is For Xtra (A Conclusion) at the time, this is a stonking great motherload of prime, often-unheard mid-’70s Residents. Christ, it’s like finding a whole new MC5 album you’ve never heard before.Familiar and recognisable in places, entirely unheard in others, from the moody “Theme from X”, to the gently beautiful “New Mexico Dream” and the borderline-prog of “Asonarose”, this an hour’s worth of absolutely crucial Residentia.

~

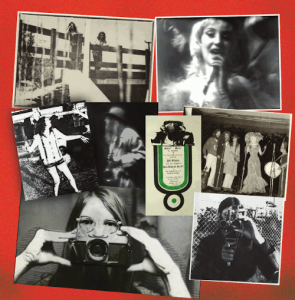

Coming as they do in pairs, Not Available is here accompanied by its companion pREServed release, A Nickle If Your Dick’s This Big. The album’s slightly off-putting title actually comes from a lurid piece of (toilet) graffiti, the particulars of which make slightly more sense when you see the photograph reproduced in the booklet. What’s contained within, however, is considerably more appetising – a first official release for the albums that were made by the “proto-Residents” in the period before the band proper was formed. Available in bootleg form for years, here they are in all their furious glory.

Coming as they do in pairs, Not Available is here accompanied by its companion pREServed release, A Nickle If Your Dick’s This Big. The album’s slightly off-putting title actually comes from a lurid piece of (toilet) graffiti, the particulars of which make slightly more sense when you see the photograph reproduced in the booklet. What’s contained within, however, is considerably more appetising – a first official release for the albums that were made by the “proto-Residents” in the period before the band proper was formed. Available in bootleg form for years, here they are in all their furious glory.

As most Residents fanatics know, during the strange interregnum between leaving their native Louisiana and relocating to San Francisco in the late Sixties, and the first Residents release proper (1972’s “Santa Dog”), there was a period of some two or three years in which a proto-Residents began their first faltering experiments around making music. With perhaps more gusto than technique, even at this blastocyst stage of their gestation, the pre-band were already adept at recording and cataloguing their output.

The fillip for these experiments had come in summer of 1970. Whilst the members were working in range of fairly mundane day jobs – at the post office, at a health food restaurant, in the records department of the local hospital and in a speciality shoe store – a musician friend of theirs from Louisiana turned up at their then-residence in San Mateo, bringing with him an enormous assortment of musical instruments. At around the same time, another acquaintance gifted to the crew a two-track reel-to-reel tape recorder which he had picked up in Hong Kong during his time on tour in Vietnam. Hmm, a shed-load of musical instruments, and a tape recorder… What to do..?Adding to their store, the members picked up whatever additional instrumentation they could courtesy of junk stores and charity shops. Quickly, they found themselves thrashing away on instruments they didn’t really yet know how to play (“This is a chord, this is another, this is a third. Now form a band”, as Sideburns magazine would famously instruct years later), recording the results, bouncing down the tracks (hey, even George Martin had to do this for The Beatles) and – praise Mary – producing music. A pick-up truck full of rusty coat-hangers parked outside their abode one day even provided them with a title for their first piece, “Rusty Coat-Hangers For The Doctor”.

At around the same time, the band’s friend Margaret Swaton – later better known in Residents lore as Peggy Honeydew – arrived to visit. Along with her came a young Englishman, Philip Lithman, whom she had met on a trip to London, and who was already a fiercely talented guitarist. Despite a rather pronounced chasm in terms of musicality, Lithman nevertheless sensed an immediate kinship with this bunch of rather oddball musical mavericks, and moved in with them, jamming and providing an infusion of fresh energy. In turn, as we all know, they provided him with his totemic name, the one he really needed: Snakefinger.

And as if things couldn’t get any more unlikely, shortly after Snakefinger arrived to shape the proceedings, up fetched

a small, enigmatic figure carrying a battered saxophone case … resplendent in a fedora, a long trench coat and sunglasses, and seemingly speaking in a guttural language of his own invention. After a good deal of gesturing and linguistic tomfoolery on everyone’s part, it was Snakefinger who finally cracked the code, informing [the crew that] they were in the presence of the brilliant Bavarian avant-garde composer N. Senada, who quickly came to be known as The Mysterious N. Senada.

Who knew that Snakefinger, whose natural habitat had thus far been Tooting in south London, would have been so keenly knowledgeable about the Bavarian avant-garde? As Harry Hill would say, “What are the chances, eh?”Even more amazingly, Senada had somehow become personally acquainted with the nascent band’s demo material, and had been so impressed that he had been forced to make the arduous intercontinental journey just in order to meet them and impart his radical musical theories. These, as we have already seen, would later become an important part of their music approach as the Seventies wore on. Really, fiction truth is stranger than fiction.

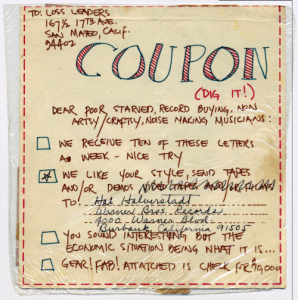

And, of course, it was at this time that happenstance intervened with perhaps the final piece of magic that the story needed in order to catalyse properly. Having submitted their Warner Brothers demo anonymously, when it was returned by Halverstadt, he addressed it to “Residents, 167 1/2 17th Av, San Mateo”. The Residents. Of course. The creation myth was thus completed. Deciding that Halverstadt really needed more acquittance with the “San Mateo Sound” (what a scene!), the crew settled down to produce another album with which to impress the Warner Brother executive. What could possibly go wrong?

Deciding that Halverstadt really needed more acquittance with the “San Mateo Sound” (what a scene!), the crew settled down to produce another album with which to impress the Warner Brother executive. What could possibly go wrong?

Well, how about sending him an album entitled Baby Sex, featuring imagery culled from some particularly unsettling Swedish pornography, and music that largely comprised of dense audio collage, including snippets of live performances (a 1971 open mic night, a party at the house of someone called Chris and, unbelievably, Snakefinger’s wedding reception). Wow, that’s really going to be knocking Cher’s “Gypsies, Tramps And Thieves” off the nation’s Number One spot, isn’t it? Yes, Louisiana’s phenomenal pop combo were surely on their way to super-stardom.

The indefatigable Mr Halverstadt, however, thought otherwise. Again, he – not unreasonably – diverged from the proto-Residents in his estimation of their future commercial appeal. Yet, the band, now proudly bearing the Halverstadtian moniker The Residents, were undaunted by this second rejection, and much was already changing in their world: they had moved into the city proper, relocating to their warehouse at 20 Sycamore Street (sans Snakefinger and Senada, who had both returned to Europe) and were already considering a raft of major new projects, including the early phases of Vileness Fats and the establishment of the creatively-independent Ralph Records. The two discs of A Nickel If Your Dick’s This Big present the material from this tumultuous period of proto-Residents nuttiness in all its glorious oddity, including The Warner Bros. Album. It isn’t polished. It isn’t professional. Hell, it isn’t really even coherent. But it is the sound of something wonderful coming together, early blueprints for later works which the band’s devotees have come to adore over the decades that have followed. And Jesus, where else are you going to be able to listen to Snakefinger’s wedding reception?Well, don’t just sit there. Snap to it.

-David Solomons-