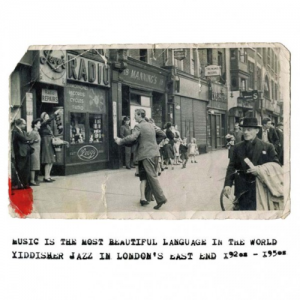

So here we are in London’s salubrious East End, in a period between the wars and reflecting a very different area to the one we know now.

So here we are in London’s salubrious East End, in a period between the wars and reflecting a very different area to the one we know now.

Except kind of not — London’s always been a mix of people, so no great surprise that ’20s London had Eastern European Ashkenazi Jews rubbing shoulders with white working class Londoners, singing songs about Copenhagen or the Netherlands. This is a record showing pluralism in the city — perhaps best exemplified by a guy from Mozambique singing a New York Jewish song in affected (and apparently mostly accurate) Yiddish.

It’s an era of jazz that’s fairly well-heeled in terms of collections, spanning ragtime, swing through to bebop with the inevitable Afro-Cuban touches; but all shot through with a distinctly Jewish sensibility – scales and rhythms from the shtetlachs and freylekhs mixing with rhumbas. There’s only a small sign of religious Judaism here — Leo Fuld‘s “Hebrew Chant” — and it’s notable by what a shift in tone, and tonality it is — it’s a chant in Hebrew over a drone. Great, but it’s not the sort of witty, charming, buoyant levity of the rest.

Much of the lyrical content that I can make out — there’s no particular regard for singing in English here, and neither should there be — is of its time: a light comedic number about beigels [sic] with the classic dad humour line “First I take a hole, then I wrap around him some bread” or a song about proposing to a woman and moving to Copenhagen (“Wilhemina”). It’s in Yiddish, but I assume Lew Stone And The Monseigneur Band‘s “A Letter To My Mother” is a loving paean to make all the Jewish mothers weep.Something that struck me while I was listening is the broad absence of (audible) percussion — there’s the occasional crash on the first beat, but by and large it’s conspicuous in its absence — perhaps more of an American thing? Where it does make an appearance (Johnny Franks And His Kosher Ragtimers‘ “Mahzel”) it sounds distinctly like clattering bits from the kitchen rather than full kits.

Possibly most strong about this record is the perverse continuity with modern-day London — while the make up of the working classes in London has broadened massively (if not changed entirely), there’s still a sense of the culture resolutely mixing up stuff. Aram Khachaturian‘s “Sabre Dance” re-figured for a comedy about a Jewish market (“A Day In The Lane”, with a chorus of “No time stopping / Not time shmutzing / Oy vey”); Ambrose And His Orchestra‘s “Selection Of Hebrew Dances” with its rendering of Eastern European numbers in a distinctly American hot jazz fashion.

Small frustration in that there’s times when the age of the recordings doesn’t quite represent the quality of the playing — Rita Marlowe‘s voice is a beaut but it’s not quite front and centre; Maurice Winnick And His Sweet Music have such a lovely, sparing arrangement (“Bei Mir Bist Der Schoen”), but still the horns shine less than they could. But this does very much go with the territory — I’ve never heard anything from this era jump out from the speakers and it’s a wonder anything survives at all.I was sort of anticipating something of a historical novelty from Music Is The Most Beautiful Language In The World, but it’s a much better record, and much more carefully curated, than merely presenting some records from a time and a place. There’s copious liner notes (always a boon) too and it’s just a lovely package. What could easily have been a schlep is definitely a mitzvah. L’Chaim!*

-Kev Nickells-

* I couldn’t resist, sorry.

- Music Is The Most Beautiful Language In The World is available from the Play Loud! online store.