Ahead of the launch of Robert Sotelo‘s début album, Cusp, Iotar interviewed Sotelo while he was in Buenos Aires from his new abode in Graz, Austria. They talked about the drift away from a London-centred culture, the glorious meaninglessness of great pop and much more that is pertinent.

Ahead of the launch of Robert Sotelo‘s début album, Cusp, Iotar interviewed Sotelo while he was in Buenos Aires from his new abode in Graz, Austria. They talked about the drift away from a London-centred culture, the glorious meaninglessness of great pop and much more that is pertinent.

Iotar spoke to the man behind the myth that is Sotelo as he metamorphosed before our eyes.

Iotar: The Robert Sotelo thing is very mysterious – there’s been a previous EP out on Susan Records and now the album is coming out. The Robert Sotelo Live band has been appearing in venues around London. Who IS Robert Sotelo?

RS: Well, I am Robert Sotelo for the most part, although also, Robert Sotelo is fictional to some extent. The mysteriousness that you mentioned is sort of ebbing away a bit; that was more to do with the initial uncertainty about what the project actually was, so in a sense I didn’t know myself for a long time, but now that’s becoming clearer to me and so I am not wearing sunglasses as much any more, really.

What about the hat?

That’s for other reasons, to be perfectly honest with you. I suppose to be absolutely frank it’s a solo moniker of sorts; the name is an amalgamation of my middle name and my mother’s maiden name, to be precise.Do you think that the name Robert Sotelo, now that is has been established, will be staying with us as a persona to express the music through?

That’s for sure. Robert Sotelo is basically who I am now, artistically, until the end.

We’ve got the Cusp album about to come out. Why this album and why now?

There was no great strategy. The album was just something that happened. Mid-2016 there was a sudden splurge of activity songwriting-wise. I can’t really quantify exactly what happened. For some reason a particular set of songs started to gravitate towards each other that I had written and it just became something.

Initially I did a first recording session with four of the songs that I had written, which came out a lot better than I thought they would, and that kind of propelled me to keep writing more. Why now? Because I am getting old and I am scared.

It’s now or never?

That phrase sums up the whole thing, really.

The song “Alan Keay” is about the sort of things that are happening regularly in the UK, it seems increasingly; is there a social commentary behind the album? Or is “Alan Keay” related to the sort of things that have happened to you?

Alan Keay was a real person and it is related to the work I do. It is a direct experience of someone going through that process, that is happening to lots of people in the UK at the moment. I think a lot of the album is about another aspect of what is happening in London and the UK now and that’s the gentrification thing. Through the process of making the album there was the ongoing issue of us slowly losing our flat. The first song on the album is about the doom hanging over you of inevitable eviction, from the investor that’s going to knock your house down.Because you had already lost your practice and rehearsal space that presumably a lot the album was conceived in?

Thats right, I live in Manor House and that area has been basically knocked down and resurrected as a new-build haven, which had been slowly and physically approaching us, literally approaching our house, so we are almost at the point where we will be eliminated in that sense. But yeah, the practice space went and a lot of the songs WERE written down there, and in my bedroom.

The whole of the Manor House area, there has been a lot of creativity down there. In fact one of the times I saw the Robert Sotelo Group was at New River Studios. On the one hand there have been things like that and various art spaces , so there’s that success that’s come to the area, but then there’s also this gentrification — it’s almost a victim of its own success.

That’s always been the paradox in places like London, hasn’t it?

Returning to the live band aspect of it, you’ve got a great live band performing material from the album, but it’s quite different how it’s played from how it appears on the album — tell us about the Sotelo live band?

Firstly, with the album I played everything, so that explains why it has a particular sound to it; it’s more naïve sounding in a way, I hadn’t made too many plans or even considered playing live for a long time. They are all people that I’ve known before throughout the years; someone like Ross Blake who plays the bass, he’s been in loads of really good projects: a noise rock band Poino, and Buttonhead. I approached him and he is someone who I wasn’t sure would be interested, but he said yes. Angus James, the keyboard player, is an exceptional musician who is also in group called The Death Of Pop.Like you say, it does sound different, I didn’t really want it to sound too much the same. It’s a good incentive for them to come up with their own parts a bit, I don’t want to be instructing them to replicate something, especially since they are much better musicians than me. It would be weird to try and dumb them down, which is what it would’ve been!

So you’re not bringing a dictatorial role to the whole thing?

I think it makes it more interesting in a way. The main body of the songs are still there.

Alex Lewis, who plays the drums is a pretty vital component, he is somebody I was making music with leading up to the Robert Sotelo project in a different band, so when it came to putting together a live incarnation of the solo stuff, he just came to mind straight away, basically. We’d been quite prolific with our other project, the summer leading up to my first recordings on my own, so he was just the ideal person, really. His drumming suits it perfectly. On the record I drum, so obviously he’s a lot more proficient than that, but he has a nice steady flow that I enjoy and he’s a pleasant person to be around.

But in fact, he is replacing a drummer from far earlier on a couple of songs, did you keep the Add Rhythm drum tracks?

There are two tracks on the album that use the Add Rhythm tracks and in fact, you are referenced in the liner notes of the album. Arguably that Add Rhythm compilation of yours did form a nucleus for some of this stuff as well, because I had intended to contribute to a compilation that you put together using these found 1960s drum tracks, but I never got around to finishing any of that at the time. I certainly continued messing around trying to write songs just using those as handy guide drums. Some of the very early Robert Sotelo stuff that probably isn’t even on the album, I probably did some of the demos using those Add Rhythm tracks. Alex doesn’t attempt to emulate the Add Rhythm style.Just to clarify for the readers, the Add Rhythm drummer was an unknown drummer sometime in the 60s based in Harrow, recording drum tracks for a couple of 7” singles which could be used as backing tracks for practice or whatever, so sort of a forerunner for our modern drum machines.

So much character in those tracks, great for messing around with. Anyway, that’s the band really, they offer a world of possibility.

You’re talking to me from Buenos Aires today, we’ve talked about London and how it is changing as a city, and scenes growing up and falling back down, and we’re talking the day after Article 50 was triggered here, initiating Brexit, with huge changes going on in the country. Being at a distance at the moment out in BA, how does that compare as city and what does that tell you about London as well?

I always feel very comfortable here, it’s a beautiful city, its definitely informed me artistically as there’s a family connection, it’s not just somewhere I am visiting on holiday. The political state here is quite bad too, they’re having a lot of problems.Buenos Aires the city itself, does that have the same problems with gentrification?

Palermo, where I am sitting right now, which I guess is the equivalent of Hoxton or Shoreditch, that’s where my mum lives. It’s a cool place, at least the weather is good so I can understand the appeal of the hipster thing here.

Where shall we go now?

Deeper.

The Sotelo Band are going to be touring with The Wharves?

Yeah, that’s very exciting, we are targeting the south coast: Margate, Hastings, Brighton and Southampton. That’s happening and is almost booked. As a live entity, Robert Sotelo is still pretty fresh, there’s a nice energy there that people are enjoying, so we’re going to vibe that out, basically.We’ve talked about the social commentary aspect of “Alan Keay”, do you think all of the songs on the album have that kind of message in them?

Not really. I almost feel that people pretend a lot of the time when they talk about the fact that a song is about something, certainly in my experience, there isn’t a lot of meaning to any of the songs really, that’s all kind of an after-thought. The actual primal process of writing the song doesn’t really involve… it’s not motivated by an initial meaning, you always apply the meaning afterwards, so in the state of actually writing a song, they’re all just kind of about nothing.

But how do you go about writing a song about nothing? Or what’s the process behind that?

To be absolutely scientific about it, I just sit on my bed with a guitar and I start playing, and then eventually I come up with some chords that I like and then I record them on a dictaphone, and then I start singing.And the words? Are they god-given? Is some divine grace speaking through you?

There are never any words, it’s melodies. I sing the melody. The vocal part could just be another guitar part, essentially, or a keyboard part. It’s just another melodic factor, really. I’m just singing nothing or just noises, its very embarrassing actually. If people were to hear the tapes of my initial discovery of some of the songs, they’re quite embarrassing.

And then how do the words apply themselves? Are these phrases that you hear out in the aether? Things that you read?

It comes down to the simple process of having to come up with lyrics at a certain point. Having to have lyrics. Avoiding having to have lyrics for as long as possible, even during periods of gigging where I’m just making things up. It’s really that I find writing quite laborious, personally. I don’t really enjoy it, so the process of coming up with words is difficult for me, but then when I do write the words I think they’re usually all right.

I write them when I have to, if I know I have to record something the next day and so usually they are quite abstract, and if there is any meaning that comes out of them, that is kind of a fluke, so after I’ve written them I think, “well, that kind of seems to be about THAT, so that’s what I’ll say it’s about.” It’s really just rhyming, trying to have phrases that are not too stupid, but don’t necessarily mean anything.

You recorded the album with John Hannon, who you’ve had a long recording relationship with; can you tell us something about the process behind that?

Well, I would say John is actually very integral to the record in a lot of ways, his editing skills. I don’t think I could have made the record without John, so in a way he’s almost like an unofficial member. Anything I sort of envisioned, he was able to help make it a reality, especially with the drumming and things like that. I can’t play the drums so well, so he made the process very easy. John is in an amazing group called Liberez and he’s done a lot of amazing things over the years, so in a sense I like working with him because he brings in an element of the avant garde. He was able to make things sound quite weird and nice, I think, otherwise it would have sounded like The Bluetones.But in a way again that’s like the late Beatles, there was this pop element but on the other hand there’s an experimental undertow which was informing the whole experience.

That’s the dream really, anyone that digs into The Beatles wants to access that balance, because that’s what makes The Beatles so interesting. John hates The Beatles, so what’s interesting about it is I’d talk to him about them and Paul McCartney and how much I wanted it to sound like “The Frog Chorus” essentially, which didn’t really happen — that was quite an interesting tension. The mid-1980s Paul McCartney aesthetic I was going for was quickly cast aside, which is probably quite sensible in retrospect. I wouldn’t say I had planned it enough to really know what I wanted it to sound like at all really, though.

So the album is coming later in the year, will that be physical, on vinyl?

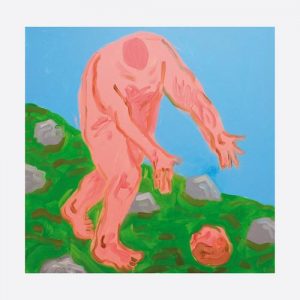

That’s right. I am in the process of piecing that together right now. Vinyl is a certainty on Upset The Rhythm. A gentleman called Daniel Sean Kelly from Leicester has made the artwork, which is something I’ve been sorting out whilst I’ve been here: it’s very striking and I think it sums up the record nicely, I can’t really describe it right now, you’ll just have to see it.I am also putting together some merchandise ideas with my manager Gemma Fleet. We’re looking at the renaissance of the beanie. I’m not really a t-shirt sort of person. I’m trying to avoid the t-shirt. I like the idea of the beanie, because it’s just a bit outmoded now. People talk about merchandise being very important these days for the artist. That’s the way they make their money now that the industry has sunk into the pit, so they have to involve themselves in having to think of these exciting promotional devices. The beanie is as gimmicky as I am prepared to get with any of this.

Cusp is out now on Upset The Rhythm.