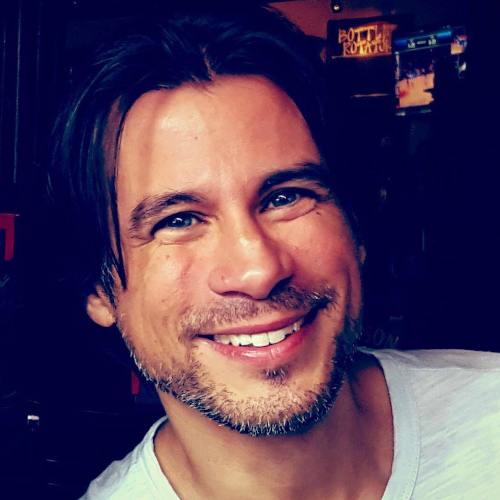

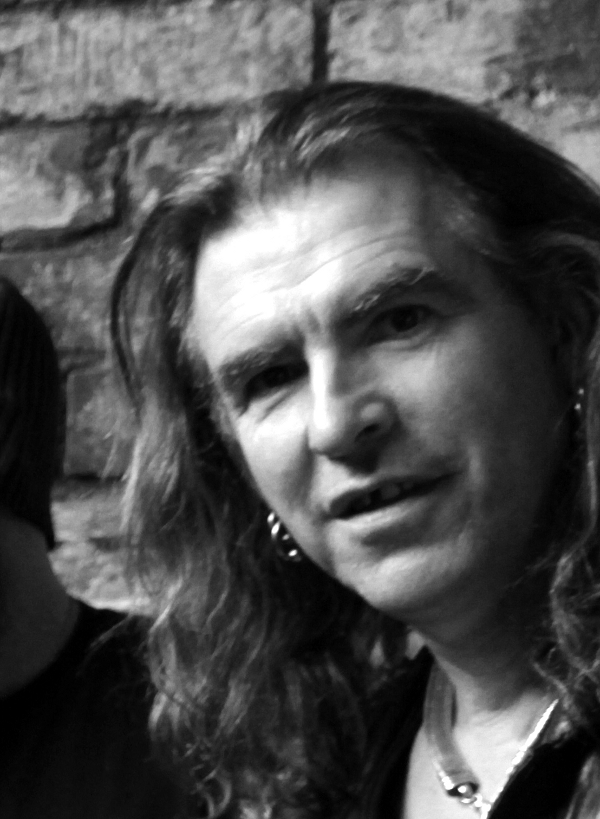

Tom Bench interviews composer and film-maker Phill Niblock as he embarks on a series of concerts around Europe.

Tom Bench interviews composer and film-maker Phill Niblock as he embarks on a series of concerts around Europe.

Do you like to keep busy?

Yes, I like to keep busy, but I’ve been doing less of a good job of it as I get older. I have a lot of gigs, but I also love to sit in my chair in front of my computer and do nothing else! The gigs start the day after tomorrow, in Switzerland.

I know that you are working with Tim Shaw for the duration of this tour, and I know that in the past you’ve toured extensively with Thomas Ankersmit, and I wanted to ask what you get from these long-term collaborations with a particular artist?

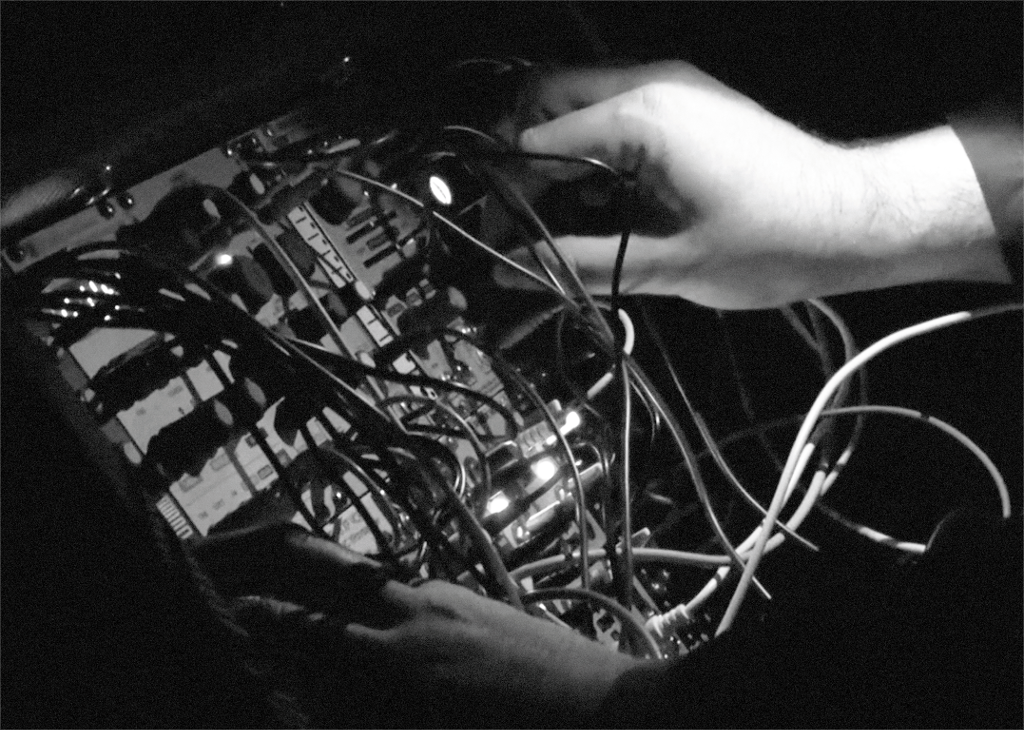

Well, so far Tim Shaw is short-term, but it could be intense. We are doing six concerts in England in the first two weeks of September, and this is our first tour together, although we don’t play together: we play two sets. And with Ankersmit, he normally does a solo set on his synth, used to be saxophone, and then he plays one piece on my set, which is a piece that I made for him. With Ankersmit it has been going on since 2003, so we are fifteen years into this concert relationship: I think we’ve probably done about fifty concerts altogether. Some years it’s intense and other years not.You do sometimes work with live musicians in your performances as well though?

I do quite a bit with live musicians as well, it just depends for each gig whether there is a musician that I know that I can work with. I just today turned down one for Bristol, because there is no time to do any rehearsal, and I can’t just give them a piece and say “do it!”. So it is better for me to not perform with live musicians.

How do you choose the musicians for your recorded pieces?

People that I have met, whose playing abilities I trust. It pretty much takes a virtuoso player for the piece to work well, because non-virtuoso players don’t play long, slow tones so well, and they often don’t understand the pieces.

I suppose the musicians need to be accomplished because you have quite precise demands on your musicians to play your music?

It’s a question of understanding what they need to do, and especially what they need to do if they are playing live with the piece. In a recording session it is pretty direct: they are only playing one tone at a time, and there is plenty of time to reflect on that and to set what the tones are going to sound like. But live, playing multiple pieces together, there are many tones and they have a lot of choices to play with, and that’s especially a problem with musicians who aren’t the ones I’ve recorded with.Obviously duration is very important in your work: could you tell me what the longest and the shortest pieces that you have produced are?

Well, for years, one of the shortest is a piece for hurdy-gurdy, which I did with Jim O’Rourke, which is only fifteen and a half minutes. There is another for bassoon which I did just a year or so ago, which is seventeen minutes, but most of the pieces are around twenty to twenty-five minutes. That’s a very good length, because then I can play, in an hour and a half programme, four different pieces at least, which are very much about sounding very different to one another, even though it is this long-tone microtonal drone stuff that I do.

So you wouldn’t see the point of going below fifteen minutes?

I’ve avoided it! [laughs]

The venue you’ll be performing at in Brighton, the Attenborough Centre, was refurbished a few years ago and has a very well-appointed sound system: when you play in venues with sound systems that are not as strong or where there are volume limitations, how do you adapt to the conditions?

Well, sometimes it is necessary to play a piece more quietly than I’d like, because of distortion on the sound system at higher volumes, but more often a piece may not work in a space because the sound system doesn’t react to it properly. In that case what I might do is just change pieces: some pieces are easier to reproduce than others.

I know that you always specify high volumes for your music: How do you feel about people listening to your music on headphones rather than on a stereo, or quietly rather than loudly?

I don’t like it, and I almost never do it! [laughs] How’s that for an answer? Sometimes when I am working on a piece I have to work with headphones, if I’m not connected to a sound system, but for the most part I don’t like headphones and I hardly ever listen to my music, as something to listen to, with headphones on. Even a home system, with a fairly normal pair of hi-fi speakers, it is not the music. You really only hear my music when you hear it in a performance set-up, with a really good sound system, and preferably with me playing the tunes!One thing that struck me when I’ve read interviews with you is that, in the past, when you had to do all of your work on tape, you weren’t able to listen to your progress on a piece until it was completely finished. Whereas now digital technology has lifted that limitation. Do you think that make a difference to the work, beyond just being easier?

I suppose it does, though I don’t quite know what that difference is. One other major difference though is that in Pro Tools I am working with 24 to 32 to 40 tracks, while with analogue tape I was normally working with eight. So a lot more is happening in the pieces made with Pro Tools, because I can use a lot more material.

How do you know when a piece is finished?

For the most part I aim for a time, which is usually twenty to twenty-five minutes, unless I want to do one that is longer. For the end of a piece, I have pitches and tones that I know are going to go on to the end, and then I start fading out other tones, so gradually that you don’t really notice that they have gone, and the piece ends with a couple of notes playing, and that’s it: it ends pretty quickly once it goes down to one or two notes.

Your pieces involve a lot of overtones and microtonal activity, and I wondered if you subscribe to any of the esoteric tuning systems and ideas of the likes of Tony Conrad and La Monte Young?

Let me quickly answer and say: no! In fact, that is exactly what I’ve avoided doing. All my pieces have random and self-determined intervals between notes. What I do with Pro Tools is I can make the microtones: I will take a tone that is recorded, say an A, and I make it two hertz or four hertz flat or sharp. But there is no particular predetermined plan to that, and certainly not something like just intonation. Unjust intonation!On a somewhat related note, how do you feel about of the term minimalism?

It’s ok. I’m actually very much more influenced by the minimalist visual artists than I am the music minimalists, particularly two of them, [Phillip] Glass and [Steve] Reich, I consider ‘repetitionists’ and not minimalists! [laughs]

You accompany your concerts usually with your films, and I wanted to ask if anyone else has ever produced a score to one of your films, and indeed if you have ever produced music for someone else’s films?

Both happen. There’s a guy in Berlin who is doing some weird stuff by sampling small snatches of long films, and he’s using my music a lot currently. There are a few other people who have used my music, and I have occasionally used other people’s music: there are four of my films that have existed for a long time which have other people’s music on them. One for Rhodri Davies, actually, who is on this tour producing us in Swansea. And the Sun Ra Arkestra, and Arthur Russell and Max Neuhaus films I made, which are very old: the one with Max is 1967.

I saw a lot of experimental films in the ’60s, for instance when Stan Brakhage was around, and I decided I was interested in making very fine resolution photography films, and I wasn’t concerned about the narrative aspect at all. So that settled it: I just started making films with nature materials, and then The Movement of People Working series from 1973, which are all very photographic. I liked to make the most of the 16mm film and the resolution, and the fact that it is now possible to transfer the 16mm film to beautiful digital video and edit and colour correct it and stuff… It is just incredible how much better my stuff looks now than it used to on 16mm. So for me, the last ten years have made a big difference to the way my films look.Phill Niblock and Tim Shaw are on tour at various UK venues from 31 August to 11 September as part of the expanded series of events circumnavigating Lost Property‘s Fort Process 2018. This interview was originally conducted by Tom Bench for Lost Property.

One thought on “Unjust Intonation: an interview with Phill Niblock”

Great interview! Any tours in the USA in the works?