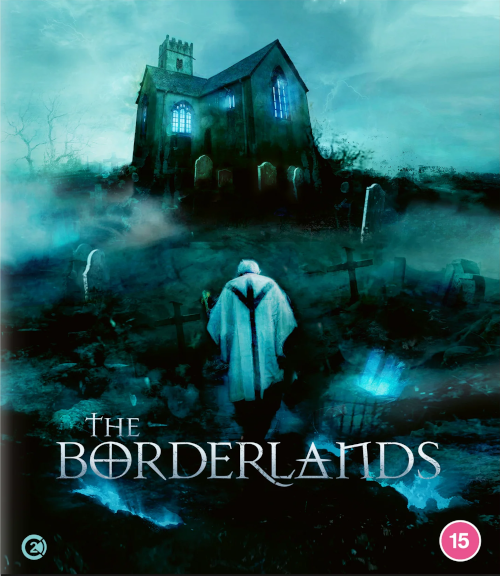

Folk horror wasn’t much of a deal when The Borderlands (AKA Final Prayer in some territories) first came out. It had rather fallen to the wayside, The Wicker Man the only one of the loose conglomeration of films that spawned the tag that still received mainstream attention.

Folk horror wasn’t much of a deal when The Borderlands (AKA Final Prayer in some territories) first came out. It had rather fallen to the wayside, The Wicker Man the only one of the loose conglomeration of films that spawned the tag that still received mainstream attention.

Well-regarded but under-seen on initial release a decade ago, The Borderlands has become something of a beloved cult favourite, one that along with Ben Wheatley’s early work was key with reviving folk at the centre of horror culture. On its tenth anniversary, this Second Sight re-release gives an opportunity to re-examine the film, and to find it even stronger than the first time round, standing head and shoulders above many of the films that have followed in its footsteps, whilst remaining kind of inimitable, a totally singular concoction.

Coming into a Devon church that has seen better days, we have world-weary sceptic Brother Deacon (Gordon Kennedy); gobshite techie Gray (Robin Hill) and the stiff Father Mark (Aidan McArdle), sent by the Vatican to investigate a potential miracle at the recently re-opened chapel. What begins to transpire threatens everyone involved pre-existing beliefs, blurring the boundaries of science, religion and something far stranger than both. The film was released into a landscape drowning in found footage films, and one in which fanboy culture seemed to swallow great swathes of independent horror whole. But rather than following the adolescent wanking-fantasists who tried to patch over their lack of imagination by bunging in a couple of Lucio Fulci references, it’s made with real love for the genre by someone who understands the rules and knows how to subvert expectations. It gets that not over-explaining things is the route to the eerie, that perfect foley work is as essential as anything else, and that believing in the characters is the the ultimate route to fear.It’s these characters that make the film. The chemistry between Hill’s knockabout Gray and the curmudgeonly Deacon is tight as anything, a totally believable mixture of irritation and begrudging warmth, no doubt helped by the dialogue’s loose improvisatory feel. It’s all the more remarkable given Hill is ultimately an editor by trade, and has only acted sparingly (notably in Wheatley’s debut Down Terrace). This relationship is explored further in the interviews that accompany the film and shines and interesting light on the process that built this chemistry, as well as the film’s often ramshackle low-budget production.

It remains a shame that writer / director Elliot Goldner is yet to make another film, because on display is a film-maker with real talent with a rarely seen ability to fuse genuinely unsettling atmospheres with characters that feel completely human, a skill particularly uncommon on a debut production. The Borderlands is a film that ought not get left behind, and deserves to stand as one of the best British chillers of its era.-Joe Creely-