There’s a lot to get through today so I’ll apologise for foregoing the introduction in favour of a rhetorical bit.

There’s a lot to get through today so I’ll apologise for foregoing the introduction in favour of a rhetorical bit.

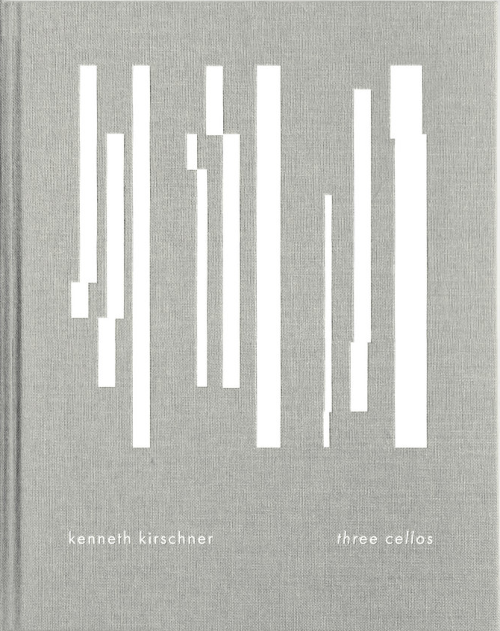

Folio is a new thing that Greyfade are doing; on top of their gorgeously designed and delivered records, they’re putting together books that complement and wrap the recordings in a load more context. We get a record, Three Cellos by Kenneth Kirschner and a book alongside it. The introduction to the book sets out their store in this regard — a record is more than just the given digital artefact, it’s an accumulation of a load of work. I don’t think the idea is to take away the recording in its place as the primary ‘form’ of a work, but there’s certainly a commitment to furnishing the recording with a bunch of context.

And to speak of forms — both books here cite Platonic forms as a preoccupation. I didn’t expect to lean on my philosophy BA, but here we are — the Platonic form usually means the idea of an idealised, usually intangible form, of a thing. When we talk about ‘what is a table’ — which philosophy graduates tend to do — we have the idea of an idealised table in our heads. The Platonic form is the conceptual being of an object.

Why does that matter here? Well both of these books involve the musicians / composers / arranger talking about what the ‘ideal’ of the ‘recording’ is. For many musicians and listeners, the ‘form’ and the ‘recording’ are the work. For composition there’s a problem — if there is a score, is the score the ‘ideal’ form? The score isn’t always a precise version of a piece of music — there’s a lot of interpretation that is undertaken by the performer, there’s material differences (whether microphones or reeds or amplification etc). The ideal of the work isn’t a single entity, but lives in a messy conceptual space between (or after) performance / transcription. Or in arguably terms proper to our philosophical times, there’s a heterogenous non-temporal conceptual space to which ‘the form’ of the work belongs.That might make a smidge more sense if I explain the work. Kirschner’s practice is largely digital, using DAWs and other digital means. Simply, he takes short samples of sounds and manipulates them into shapes that he enjoys. And so our book tells us what this means. On the one hand, Kirschner is happily self-effacing — glad to talk about being less confident in the realm of notation. On the other, his method evokes complexity — there’s mention of his compositional ‘method’, asystematic as it is, having a gazillion potential outcomes. For non-British readers, a gazillion is a playground number that roughly translates to a fucktonne or fuckton.

And what does Kirschner do? Well, he takes a sample of a cello. He has two axes which he manipulates, time and pitch. You can think of it as knob-turning, which he invites the reader to do. So he overlays cello one with a copied and pasted cello two, where two has a different pitch or length or both. And sometimes a third cello. If he likes it, he captures it, and starts again.So we learn that the process is intuitive and exploratory — largely this is Kirschner working with limited means to produce simple conjugations of sound. The original sample is non-metric, so the outcome is in a messy, non-metric space (I mean as in it’s not a sample of 1-2-3-4). Kirschner talks about the kinds of melodic material he’s using — relatively limited, four notes in a row. But in the process of overlaying, changing pitch and tempo, the relationships between the two-or-more notes brings out new tonal ideas. Further down the line, Joseph Branciforte finds means to transcribe these irrational loops and themes. Which in itself is a bastard difficult task, written in extensive detail.

So here’s part of where the book idea is an excellent addition. We learn that Kirschner, in his early days, was trying to find ways to emulate Morton Feldman. I mean who wouldn’t? Feldman is bae. And this technique, described later by Branciforte as ‘irrational canons’, produces a harmonic world that is close to Feldman. Close in the sense that it has an icy, reserved terror about it. And distant in more proper terms — the dissonances and chords, timings and overlaps are of an entirely different nature to Feldman’s small, powerful gestures in established harmony.And the book leaves us in no doubt also; putting this stuff down on paper is arguably an act of self-effacement (despite being more, um, face-ful). Personally speaking, I really appreciate this. Experimental music in the last decades has tended towards quietism. Record sleeves don’t feature people’s faces, there’s rarely more details than the minimum (producer, label, website address). The art itself is frequently a few colours, a simple design. As little detail as possible.

It’s possible, in that context, that Greyfade’s gamble is to over-expose themselves. I wouldn’t say that Kirschner’s writing on method makes the work repeatable, but it does make it transparent. In the context of a world where I have dozens of near-blank CDs with inscrutable names, it’s revelatory. And moreover, generous to an audience that is, typically, super-geeky. It’s a distance away musically, but if think of the difference between Autechre sleeves — opaque and indistinct — and the degree of detail parts of their fanbase to to discover how they make their sounds. I’ve concentrated on the book here, but it’s a magical recording. All the details about the state of recording from the book mean that all the details of the recording in the recording jump to the front. And in some ways are complicated by the book — there’s speak of how Branciforte’s transcription used details (bowings etc) from the original samples which are complexly composer’s details — did Kirschner mean those upstrokes?The cellist (Christopher Cross) is a magical player. Kirschner speaks of his problems with vibrato and I can see where he’s coming from; but Cross’s vibrato is always judicious, never flowery or obfuscating poor tonality. A real gift to some music that might otherwise be arid — this isn’t strictly ‘atonal’ music but it’s also not traditionally ‘tonal’ either, and so having just a soupçon of humanising influence makes for a kind of burnishing quality to the music. Possibly the best compliment I can give the recordings is that they’re improved by the book, and I’d implore listeners to be readers also.

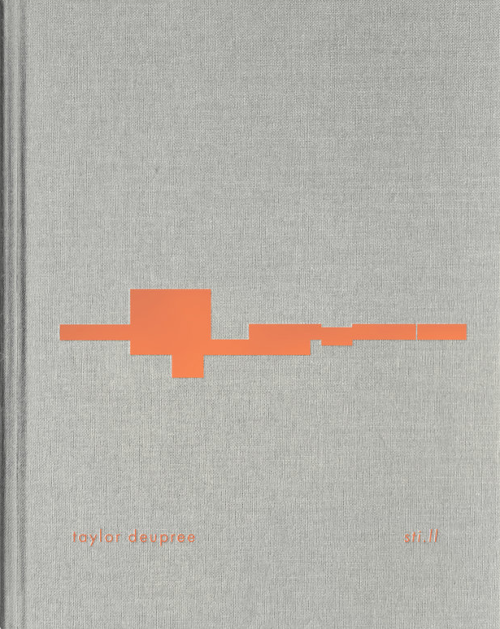

Next up is Taylor Deupree‘s Sti.II, a transcription of an earlier work of his, Stil. And that facile description does a massive disservice. Again, to speak of Platonic ideals — what is the form of the work?

Next up is Taylor Deupree‘s Sti.II, a transcription of an earlier work of his, Stil. And that facile description does a massive disservice. Again, to speak of Platonic ideals — what is the form of the work?

These questions may seem like sophistry (to use another Attic term), but I’d argue that these works have that context. Not all musicians and listeners think like this, but many of us (I live in both camps) get enjoyment out of those kinds of details, out of situating a piece within its context.

So the original (I should ‘originary’) Stil was an earlly ’00s piece. It’d probably be described in terms like ‘minimalist electronica’. It passed me by at the time, which is remiss. It’s a gorgeous record — all slowly shifting pulses like a blurred-focus skipping CD. And thanks to Branciforte’s work in realising Sti.II, I’m going to seek out my own copy. But I’m not here to talk about that.Sti.II works where it deviates from the original. While the detail of the original is very clearly digital means, Sti.II uses a bunch of extended techniques to realise it. It is imperfect; it’s clearly the same record, but it’s like the other side of a mask or some other inversion — demonstrably the same yet uncannily dissimilar.

Personally, I can’t get enough of this detail. It’s surely an act of no small generosity to say to the readers “look, we’re not just alluding to making these sounds — we can show you how too”. Again, I don’t think this make Sti.II repeatable (and why would anyone when Branciforte’s recording is exquisitely tight?) but it does open the door to musicians to expand their pallete. Despite this being by no means ‘mainstream’ music, Greyfade / Folio are the opposite of obscurantism.

And so the book for Sti.II deals in questions of Platonic ideals and how one transcribes things and we arrive at a point where all the differences between source and product are clear. We see how Branciforte’s transcriptions find ways to bring order to complex non-quantised loops, how to impose a kind of grid on the rhythmic understanding of the piece without lending the music a flattened, regular meter. It’s also, arguably, making some complex and tricky musical ideas approachable, or at least conceptually attainable. There’s a line in one of the books about “…the platonic perfection of a digital fade-out…” [p59] which is an excellent articulation of how Sti.II differs from Stil — instruments will crack and distort as you play them more quietly, while a digital fade out will uniformly disappear. What this book isolates, like an overpowered floodlight, is how an acoustic version of an electronic piece is constantly and consistently different. And so the listener is lead into a world of paying close attention to timbral differences, to getting their ear-hands all around the distinct shapes of digital vs acoustic instrumentation.Also importantly — because of Platonic ideals it’s often the case that the composer is elevated relative to the performers; we know Mozart‘s name but not his soloists’, let alone the third flautist. These books give the instrumentalists time in the sunshine too. The clarinetist on Sti.II, Madison Greenstone, is given space to articulate what she did, how she approached the record. It’s important that we recognise that these things don’t happen without clarinettists like Greenstone figuring out a way to play the clarinet on her back with water on the bell. And also she intuits the Grecian undertones to the books by talking about the ship of Theseus.

This has been quite a long piece so … apologies for that. But fundamentally, these are gorgeously presented items and hugely generous in a way that is atypical, I’d argue, in experimental music. Greyfade deserves many’s the plaudit for these works that point to a culture and a community of breathing, bleeding humans that produces a record, not merely a product in a marketplace of roughly-identical products. Kudos, herr Branciforte.-Kev Nickells-