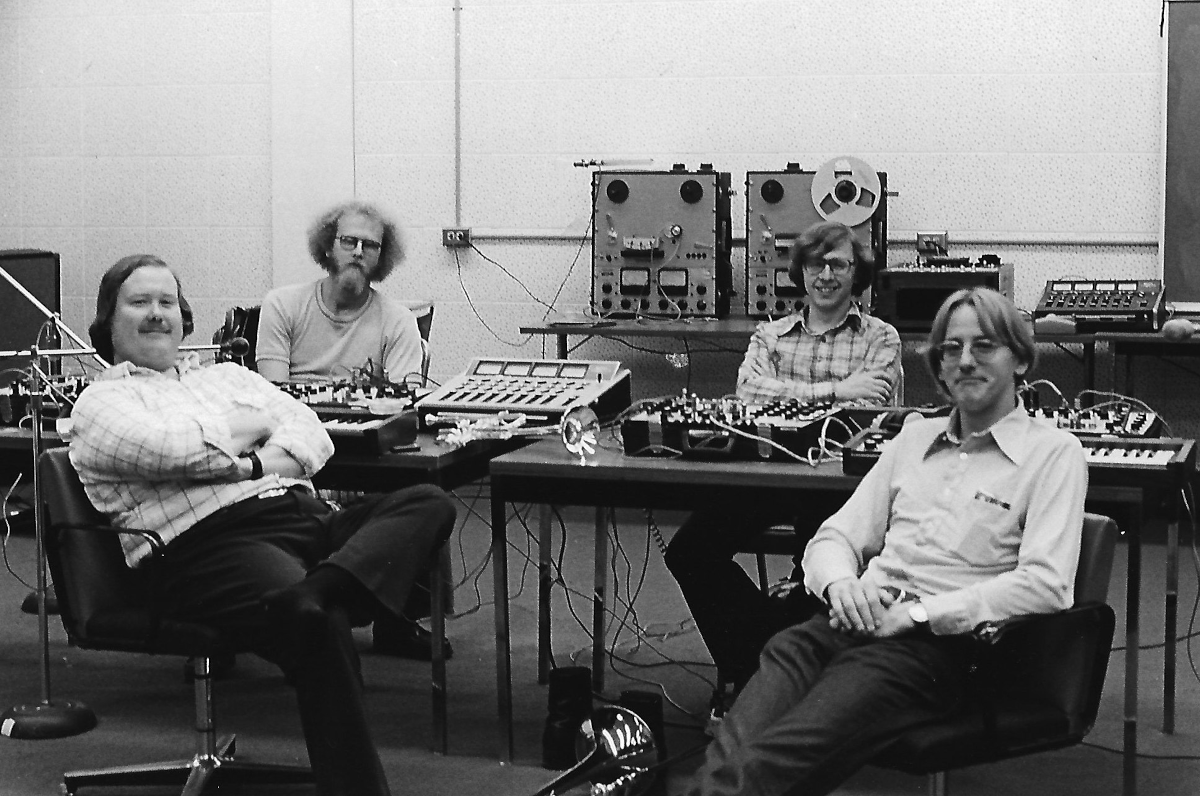

Active since 1971, the Canadian Electronic Ensemble has the distinction of being the longest-running live electronic music formation in the world.

Active since 1971, the Canadian Electronic Ensemble has the distinction of being the longest-running live electronic music formation in the world.

Their session for Philippe Petit‘s Modulisme project showcases the sort of modular synthesis sounds that the ensemble have been performing annually in Toronto and on tour around the world for over fifty years. The current membership includes founder members Jim Montgomery and David Jaeger alongside John Kameel Farah, Paul Stillwell, Rose Bolton and David Sutherland, who have joined the group at various points over the last twenty-five years.

Freq spoke to Jim Montgomery, David Sutherland and David Jaeger about the CEE’s recent Modulisme session, and they reveal some of the wisdom accrued from many fruitful years of playing modular synths together and in other contexts.

When did you first become aware of modular synthesis as a particular way of making music, whether as part of electronic music in general or more specifically as its own particular format, and what did you think of it at the time?

Jim Montgomery: I started making electronic music in the ‘70s. Modular was pretty much it unless you wanted to do [musique] concrète.David Sutherland: Wendy Carlos, 1968; it was clearly a modular making the music, there was a picture on the LP cover. Before that I was hearing stuff on the radio but had no idea how you made that music.

David Jaeger: Much like Jim’s answer, I started making electronic music in 1970 at the University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio (UTEMS). The studio was, essentially, a room-sized modular synth. But you could also do musique concrète there quite nicely.

What was your first module or system?

JM: First system was a Synthi A. First modules were VCOs, VCAs and thirteen-step sequencers built in the NRC music lab by Hugh Le Caine.DS: A Synthi AKS at Concordia University in Montreal.

DJ: Aside from the UTEMS experience, my first portable modular system was the EMS Synthi A.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

JM: Still working on that. Thankfully, it seems a never-ending process.DS: In Montreal, in 1972 there really weren’t anything but modular synthesizers; so if you had a synth, it was modular. One of the great things about the Synthi was the patching was physically separate from the module controls. This encouraged building a mental model for how to patch which didn’t take long and encouraged the development of troubleshooting skills.

DJ: The patching system in the Synthi A was so self-evident, it took no time at all to understand and to work with.

Do you prefer single-maker systems (for example, Buchla, Make Noise, Erica Synths, Roland, etc) or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components form whatever manufacturer that match your needs.

JM: The latter.DS: Based on my early experience with the Synthi, I have become old and grumpy and haven’t the patience anymore for poking around in a mass of cables to adjust a knob if I’m playing live. That sensibility is making single-maker systems more attractive than in the past. The Moog DFAM, SubHarmonicon, Arturia MiniBrute 2s and even Behringer‘s Neutron are very interesting that way. I have a friend who hates this idea. They need to have the patch point and the knob close by for things to make sense for them.

DJ: I don’t have a preference, although the unified system approach makes things rather convenient.

East Coast, West Coast or No-Coast (as Make Noise put it)? Or is it all irrelevant to how you approach synthesis?

JM: The latter.DS: Marc Doty gave an interesting presentation at Knobcon where he pointed out that east coast / west coast is mostly a marketing concept rather than an engineering term. Bob Moog started out making synths for academic institutions. So did Don Buchla. The Moog ladder filter was designed at the request of Gustav Ciamaga who was at University of Toronto Electronic Music Studio. At the time, most academic composition departments were focused on serialism and its derivatives. Mills College, where Don was hanging out, was a bit of an outlier in this regard and the music that came out of the Bay Area was a little more “tuneful” than typical academy. Bob Moog sold to rock musicians who loved tunes.

So when you think about it, there is a lot more in common with Buchla and Moog. I just don’t think the presence of a wavefolder or a lowpass gate is as significant as many people think.

DJ: I find no affiliation with a coast — I’ll play with whatever you put in front of me.

Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

JM: I don’t actually make that distinction.DS: Almost always effects these days. Usually playing live I’m patched into Ableton Live. Recording, always into Live.

DJ: I associate with the notion of the “Maximalist” — that is to say, I always want more than the system will provide.

Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

JM: Depends on the context. If I’m working alone, I almost always multi-track. With the band, it’s almost always straight to post.DS: Either or. Paul [Stillwell] and I have been playing together online for the past year using Audio Movers. I download Paul’s stems and edit our improvisation with glee, frequently cutting and occasionally adding a bit where there seems to be an opportunity. Then I ship it off to Paul who does the final mix and mastering.

DJ: I’m happy either way!

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

JM: I tend to pre-patch.DS: That is the great thing about the Synthi and Easel. They patch really well in a live context.

DJ: I would pre-patch, but then modify as I go… more interesting that way!

Which module could you not do without, or which module do you use the most in every patch?

JM: VCO(s).DS: The Synthi and Easel seems to me to be modules in and of themselves. There was this three-module challenge going round a couple of years ago. A great idea for practice for sure. But, you get a Maths, a Spectral Multiband Resonator and a Clouds and you can do some pretty amazing stuff. I’m sure that combination of modules has many more transistors than the Synthi and Easel combined because of the microprocessors. It would be interesting to see an “as many modules as you like but a limit of 300 transistors” challenge. The Serge folks would kill at this.

DJ: I could not do without filters.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

JM: Fish gotta swim, birds gotta fly. It’s a partnership. The system has as much say in the results as I do.DS: Modulars make it easy to make music that is based on sound rather than have melody or harmony baked into the instrument.

DJ: A certain “Funkyness” — please forgive the term..

Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

JM: Other than Reaktor, which I like, I haven’t had much experience with or interest in the others.DS: Love ’em, was playing with VCVRack a few minutes ago.

DJ: Yes, and I think they are terrific! Reaktor — and I use it in conjunction with Wavelab. I’m OK with these.

What module or system you wish you had?

JM: Synthi 100DS: I want to sell off a whole bunch of Serge and Eurorack stuff. Not really sure what I want next.

DJ: I don’t envy some other system, particularly.

Have you ever built a DIY module, or would you consider doing so?

JM: I have, but at this point, probably won’t again.DS: Yes and I suck at it. Wish I was brilliant at it because I have so many ideas.

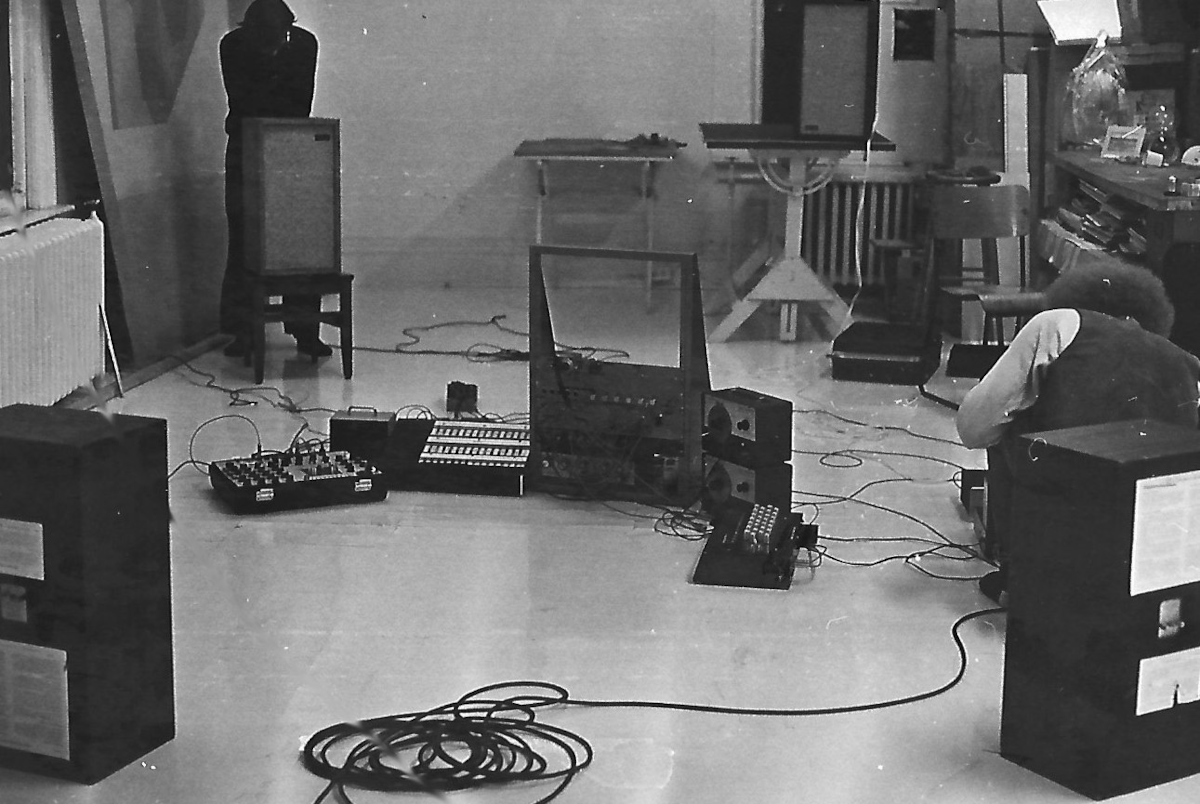

DJ: Back in the early 1970s I built a thing we called the “Dynasoar.” It was a modified Dynaco pre-amp, wired with a feedback loop, but with controllers inserted in the feedback circuit. If you listen to the CEE’s composition October 4, 1974 you’ll get a pretty good idea.

Which modular artist has influenced you the most in your own music?

JM: The artists who influenced me are mostly the ones who started it; Stockhausen, Berio, Risset, the usual suspects. I would characterise my relationship with other artists to be essentially appreciative for the past forty years or so.DS: I’m terrible at remembering names, but I have to say I am very inspired by the many young women that are getting into it these days.

DJ: Karlheinz Stockhausen, Dennis Smalley and Ragnar Grippe.

Can you hear the sound of individual modules when listening to music since you’ve been part of the modular world — how has it affected (or not) the way that you listen to music?

JM: Yes, but it’s analogous to hearing violins and violas and it doesn’t change the way I listen.DS: Can’t say that I do that.

DJ: I think it all depends on the context in which they are used. I do tend to listen for the overall blend, but my brain wants to sort out the details. So it’s a multi-layered experience.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

JM: The CEE has several projects at various stages of development. I’m releasing my First Symphony sometime in March (2022).DS: Paul and I have a project called Not Your Average Worker Bees and we are in the process of releasing our first album on Bandcamp and we have a second one lined up.

DJ: Upcoming is a release of my work, Spirit Clouds, with accordion soloist Joseph Petric. It’s a work for free-bass accordion and electronic sound tracks. Another version of the work, Constable and the Spirit of the Clouds, is in the works, likely coming out in the fall. This version is for viola and electronic soundtracks.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

JM: For live performance these days I use a Behringer Neutron and Pro-1, a Dreadbox Typhon and the Synthi A. An EG from each of the Neutron and Pro-1 are routed to the Synthi and then patched internally. The Typhon stands alone.DS: Here is the thing. Usually I can’t recognise what part I’m playing when playing back a CEE track a week after it is recorded. Which is fun because I can listen to the multitrack and wonder how I made that cool sound. Sometimes there is a little flash of worry that was the last good sound I would ever make. Playing so much with Paul online during Covid has softened that reaction. I don’t know where the sounds come from and it’s not my job to know. I just need to show up and listen and go looking for some more sounds.

DJ: I prepared several voices in Reaktor and assembled them in Wavelab.

Who would your dream collaborator be for a Modulisme session or otherwise?

JM: I’m pretty happy with my band-mates, but I like collaboration and would work with almost anybody.DS: I don’t have a good answer to that question. I hope that I would be open to playing with anyone who was attracted to playing with me. You see that a lot with blues musicians.

DJ: Sarah Belle Reid would be a very cool collaborator.

*