San Francisco residents Thomas Dimuzio, Tom Djll and Gino Robair are three leading lights in the world of improvisation and modular synthesis. All have been active on the ever-bountiful Bay Area experimental music scene for many years, and are interviewed below about their individual contributions to the Modulisme sessions organised by Philippe Petit. Their answers reveal the many and varied approaches, options and possibilities that the form offers not only to three intrepid musical explorers, but more widely.

San Francisco residents Thomas Dimuzio, Tom Djll and Gino Robair are three leading lights in the world of improvisation and modular synthesis. All have been active on the ever-bountiful Bay Area experimental music scene for many years, and are interviewed below about their individual contributions to the Modulisme sessions organised by Philippe Petit. Their answers reveal the many and varied approaches, options and possibilities that the form offers not only to three intrepid musical explorers, but more widely.

When did you first become aware of modular synthesis as a particular way of making music, whether as part of electronic music in general or more specifically as its own particular format, and what did you think of it at the time?

Thomas Dimuzio: I had been aware of modular synthesis throughout my life, but the timing just never worked out so well. When everyone was dumping their analogue systems in the mid-’80s I didn’t have the money nor foresight to invest in some of the older modular beasts. At the time I was also on a path to all things digital sampling. Sampling was a modern approach to music concrete and kept my attention for decades to come. It wasn’t until visiting the 2012 NAMM show that I realised modular systems were back, and back with a vengeance. It was at this point that I decided to dive in head-first, thereby christening my “mod-life crisis”.In the early 1980s, I purchased a Sequential Pro One, which was my first foray into analogue synthesis. I loved that machine, and still have it to this day, but it also eventually biased me, and in a negative way, especially after migrating to sampling. Simple wave shapes of sawtooth, square and triangle were of no interest to me at the time. Perhaps it was more about the limitations of the Pro One, but there was no comparison of simple wave shapes to the complex waveforms of a digital sample.

Now with the Buchla I have a newfound admiration for basic wave shapes and how they’re malleable from ultra-slow to hyper-fast and can instantly turn complex via frequency modulation. Now I love my sines, squares and sawtooths and the countless functions they serve in electronic music.Tom Djll: “Modular synthesis” is a definition that is pretty recent in my experience, if it means that the idea of “module” comes before style, maker, format or system. When I learned of the Serge Modular Music System in 1980, maker/system was foremost in my mind as the defining factor of the instrument. As I learned more about that system, “patch programmability” became the most important factor about it.

What was your first module or system?

Thomas Dimuzio: My first modular was a Buchla 200e which I purchased directly from Don Buchla in Berkeley in 2012. Since then I haven’t stopped expanding the system, which has now evolved into five distinct cases. I also dove deep into Eurorack around the same time.Tom Djll: As the previous answer implies, the Serge Modular Music System was the first I owned. In college, I first encountered electronic music production in a fancy electronic music studio with an EMS Synthi 100 and a Scully 8-track tape machine. My first experiments were on that massive system, but since I had scant training, not much came of it. I learned much more through the excellent Serge manual, which covers all the basics. By 1983 I had wired a four-panel system from kits, and was doing a gig here and there.

Gino Robair: It was a couple of Buchla 200-series modules that were part of the system David Rosenboom used for his pieces based on brainwaves. A decade later, I added a couple more modules to it. Later, I built a Frac-rack system with modules by Blacet, Wiard and Metalbox.

How long did it take for you to become accustomed to patching your own synthesizer together out of its component parts?

Thomas Dimuzio: At first I had the audacity to think I knew what I was doing. Technically I knew what oscillators, filters, and envelopes were, but I quickly realized it’s all about the interaction and nuance between these modules rather than their specific functions. I’m still learning many of the system’s intricacies as it’s a constant realm of discovery and finding new musical workflows.Tom Djll: Not long. My training in improvisation ingrained in me the total acceptance of whatever is happening, and therefore a similar willingness to work with whatever tools are at hand. I was quite happy to let the circuits speak their raw native language, rather than me impose pre-determined musical structures and tonalities upon the circuits. I have quite a bit of keyboard training and compositional experience, but I don’t generally incorporate much of that into my electronic music. I prefer it raw and immediate.

Do you prefer single-maker systems (for example, Buchla, Make Noise, Erica Synths, Roland, etc) or making your own modular synthesizer out of individual components from whatever manufacturer that match your needs.

Thomas Dimuzio: Yes, I prefer the Buchla, mainly for its visionary design and consistency from module to module. Inputs on the bottom, outputs on top, colour-coded CV routings, 4U modules (ie more real estate for the fingers) and out of the box designs make it an instrument that’s continually inspiring and compelling. The Buchla conforms to many of my tried and true workflows, while inspiring many new ones as well. Systems and modules from Make Noise, Mutable Instruments, 4ms and other manufacturers are also equally inspiring across my Eurorack system, which focuses more on sampling, looping and processing.Tom Djll: Whether it’s from individual circuits or modules or racks, I want to put together the best instrument for the job at hand. It’s my main form of composition, along with putting together ensembles. When I started putting together Eurorack systems, I put in two years of research before making a purchase, and by then had a pretty good idea of what I wanted. I bought eclectically, from a bunch of makers, but I gravitated more toward Make Noise modules, since they seemed to have absorbed deep lessons from Serge. Also I saw that Tom Erbe was on their team, and I knew his name from my time at Mills College. DSP master!

At the moment I have three Eurorack systems (broken up from one large system), the Eurorack lunchbox, one XL-boat Serge panel (Random Source: Mantra + Donks + WVM/RESEQ) with two more in assembly, four BugBrand devices, two Koma Field Kits for electroacoustic work, and some circuit-bent doodads. Those are the active parts of the studio.Gino Robair: I’ve discussed this topic a lot with Alessandro Cortini, who feels strongly about it: there is definitely something musically interesting when you keep the system confined to the modules of one company, particularly if they were created by a designer with an “attitude” or a strong vision about the potential of electronic musical instruments — for example, Don Buchla, Serge Tcherepinen, Grant Richter of Wiard, Tom Bugs of Bugbrand and so on.

In those cases, the modules reflect the developer’s aesthetic sense, and they will have a distinct sound and suggest particular ways of working. As a result, it might not be able to do everything, but that’s fine for many of us. If you need a general-purpose synth sound, there are tons of low-cost options.

But eventually you come up against a problem: What if you want something different and your favourite developer doesn’t make the kind of module you want? Do you create a new system or dilute the pure system with a third-party module? This is more of a recent issue because of the market penetration of the Eurorack format. Back around 2000, for example, the Frac-rack and 5U formats were strong, particularly in the DIY world; Doepfer had a nice selection of modules, but was still making his money with MIDI controllers; and other folks were getting ready to introduce their own proprietary formats such a Wiard and Metasonix.Bob Moog‘s Moogerfooger line was, as far as I was concerned, a modular system: I mentioned this in my review in Electronic Musician magazine, and Bob later emailed me and said that, in a sense, that was his intent. And they make a damn fine modular if you use them as such (and have the CP-251 Control Processor).

East Coast, West Coast or No-Coast (as Make Noise put it)? Or is it all irrelevant to how you approach synthesis?

Thomas Dimuzio: West Coast in the sense that I enjoy being the conductor of a generative electronic symphony. However, I don’t subscribe to any philosophy when it comes to making music. Everything and anything is possible and applicable.Tom Djll: Irrelevant. I never heard those terms in the seventies, eighties or nineties. I absolutely love “West Coast” LPGs and Buchla bongo sounds, but I’m also obsessed with filters, which are said to be “East Coast”.

Gino Robair: Depends on the project. If I am playing melody/harmony-based music, I’ll use a traditional keyboard synth with the standard VCO-VCF-VCA (East Coast) configuration. But for improvisation and sound design, I like to work with self-generating patches in the West Coast style.Do you tend to use pure modular systems, or do you bring in outside effect and devices when playing or recording?

Thomas Dimuzio: I’ll bring in the kitchen sink if it’s relevant to a good performance, composition, or to suit a patch. Outboard effects have always been essential in the work that I’ve done, and it’s also nice to plug-in odd gadgets and sundries into these systems, and there are plenty of those around these days. For live shows I’ve been plugging in a Teenage Engineering OP-1 into the Buchla SkyLab and more recently running the OP-1 through a Red Panda Tensor. The output of the Buchla goes straight into an Elektron Octatrack for live looping and processing. It’s a powerhouse setup for performance and portable enough for air travel.Tom Djll: I love electro-acoustic music, so I often bring in outside sound sources – mainly trumpet, but also percussion and junk, piano, bells, music boxes, and samples of field recordings and found musics. And of course, who can go for long without some healthy feedback?

Gino Robair: There is always some other item patched in. Part of my aesthetic is to bring something new to each gig or recording session (eg a stompbox effect, a lo-fi sound source, etc.) and leave something I usually rely on at home. That is how I challenge myself. I also avoid using looping pedals and rarely use reverb (except in extreme ways). I like the raw sound of the electronics.Do you find that you record straight with no overdubbing, or do you end up multi-tracking and editing tracks in post-production?

Thomas Dimuzio: It depends no the situation, but for the most part I’m recording straight in and without overdubs. The problem is that I rarely go back and work with many of those recordings, but once I do choose a recording, then anything goes with overdubs, editing, processing/reprocessing all suiting a more compositional approach. I love just hanging out with the synths while patching and tweaking on the sounds they emanate.

Tom Djll: I don’t lean one way or the other. My Modulisme session happens to be dual mono with no overdubs, but my most recent release, Failed Ecosystems, is multi-tracked and edited down to some millisecond-long events as well as structures that last ten minutes or longer.Gino Robair: On an improvisation session, it’s straight into the DAW, no overdubs. But I very much enjoy multi-tracking and editing sounds from my modular systems into compositions.

Do you pre-patch your system when playing live, or do you tend to improvise on the spot?

Thomas Dimuzio: I use a smaller Skylab system for most of my performances and tend to stick with an all-purpose patch that lets each module shine within the scope of the system. I may add or pull a cable or two while playing, but the patch is largely static and essentially the same from show to show, but with small evolutions. With a larger system and for quadraphonic output, my patch is largely constructed before the performance, and the pre-patching greatly varies from show to show. The last thing I want to do it to build a patch in front of an audience. It’s all about building the patch first and then stepping up to play it live.Tom Djll: I live and breathe improvisation, and I find that ideas, including pre-patching, lose their usefulness once the music starts. Of course, I’m tempted to pre-patch every time I find something at home I like, and have a gig coming up. The system I used for the Modulisme session I always leave patched, but it generates random results. The Mister Grassi module sort of re-patches itself internally after each touch!

Gino Robair: I usually start from scratch when playing live: I like being surprised by the instrument, so I show up with the synth unpatched. Once in a while I will create a basic patch during soundcheck. If I am improvising with acoustic instruments, I find it easier to patch on the fly rather than showing up with a complex pre-set that I have to untangle in order to fit into the music.Which module could you not do without, or which module do you use the most in every patch?

Thomas Dimuzio: I’ve got to say it’s the 272e Polyphonic FM Tuner. I absolutely love pulling sounds out of thin air and warping them via envelopes and filters. The 227v Verbos Time Domain Processor makes a great pairing with the 272e. It’s noisy a beast, but compliments the radios with its micro-looping and noise floor. Another great pairing is the Northern Light Modular Electric Dompteur hED with the quad planners of the Buchla 227e System Interface. The results are beyond stunning and absolutely mind-blowing when it comes to real-time spatialization.

Tom Djll: There are two that I come back to again and again, in Eurorack: the Make Noise Morphagene, and the WMD Synchrodyne+Expander. The Morphagene is the sample player of my dreams. The controls and the way it plays (like an instrument!) are exactly what I had been dreaming of since the mid-’90s. The Synchrodyne+Expander is a bottomless well of experimental sound-making. I’ve been working with it for five years and it still surprises me, every session.Gino Robair: I have no favourites. I’ll play whatever you put in front of me.

What do you think that can only be achieved by modular synthesis that other forms of electronic music cannot or makes harder to do?

Thomas Dimuzio: For me it’s been electricity. Moving away from the coarse granularity after decades of MIDI-manipulated sampling, synthesis and processing and into a realm that is fast as the speed of light has been fascinating in every aspect. Using Buchla 200-series analogue clones, I’m able to slow down oscillator cycles to thirty-two minutes, and envelope cycles to thirty-six minutes.This may sound extreme, but it’s a way to freeze time, or put actions into motion that s-l-o-w-l-y evolve, if not imperceptibly, over time. Being able to execute this on the fly, and even override or reject such actions after putting them motion, makes the system entirely interactive and in a sense even faster than realtime, in that a split-second decision can unfold over time, and in ways that I can anticipate as an improvisor/composer. Such a flexible and tactile approach to sound is not innate in most other systems.

Tom Djll: The immediacy of working with raw circuits is crucial to my soundmaking.Have you used various forms of software modular (eg Reaktor Blocks, Softube Modular, VCVRack) or digital hardware with modular software editors (eg Nord Modular, Axoloti, Organelle), and if so what do you think of them?

Thomas Dimuzio: I greatly appreciate software emulations of modular gear and virtual synthesizers. It’s an incredible way to learn the basic principles and the ins and outs of rare and expensive instruments without obtaining the physical hardware. They’re also great for mixing in the box. I like being able to recall a mix in Pro Tools without having to sweat external hardware settings. In fact, with most modular rigs it’s very hard to get the exact same sounds from a patch twice. The Buchla is good for this as it can save your preset (sans wiring), but I use the Buchla preset manager more as a performance tool than a patch librarian. The 259e and 296e software emulations by Softube are spot on.

Tom Djll: I have zero experience with any of those. I farted around with a Crystal softsynth running on Peak 6 a long time ago. When I was at Mills I studied computer music and learned that making music on computers was something I hated doing. Probably picked up from years of playing the trumpet – when I get my hands on an instrument, I expect to be making sound immediately. Having said that, there are a few smartphone apps that I’ve incorporated into my live playing. One of these apps is so old and unattainable now, I keep an older iPhone on hand just to run it.Gino Robair: I enjoy working with VCVRack in the studio, but a virtual patching environment doesn’t fit with what I do live. Years ago I met Stephan Schmitt, the man who created Reaktor. I was carrying around my Doepfer P6 case filled with Eurorack modules and he said: “You can do all that stuff, and more, a lot easier with Reaktor on a laptop”. It was an interesting challenge and I took him up on it: over the course of a year, I assembled an environment in Reaktor that worked for improvisation. But one night my laptop wouldn’t boot up, and having a back-up drive was of no use. So I returned to hardware when I tour, which I augment with apps on my iPhone and iPad.

What module or system you wish you had?Thomas Dimuzio: The system I wish for does not yet exist.

Tom Djll: I’ve been reconfiguring my systems continually, and I find that re-racking your gear is a great way to get a new instrument – and new reflexes – out of gear you already have. I’ve never used a Buchla system – the original 100 at Mills was out of commission when I was there (and I had my Serge, which was way more powerful; even the faculty members said so). But I’d like to work on a Buchla system. If I ever win the lottery, I might even buy a system. But it’s more likely I’d just buy tons more Serge panels.

Have you ever built a DIY module, or would you consider doing so?Thomas Dimuzio: I’m a butcher when it comes to soldering and I have no electrical engineering chops. It’s been great to be able to purchase modules built by experts such as Mike Peake, Roman Filipov, Django’s Fire and others via Reverb.com. I’d love to be able to build a module, but there isn’t enough time in the day for me to get into it.

Tom Djll: Not really interested. I want to play!

Which modular artist has influenced you the most in your own music?

Thomas Dimuzio: It’s hard to say, but I do love the work of Morton Subotnick. Mort is the man responsible for the Buchla, so I owe a great debt of gratitude to him and Don Buchla for building such an inspiring and open-ended electronic musical environment.Tom Djll: Thomas Lehn, without a doubt. And I’m in awe of what Richard Scott has been putting out the last few years. Thomas Ankersmit does great work too.

Can you hear the sound of individual modules when listening to music since you’ve been part of the modular world — how has it affected (or not) the way that you listen to music?

Thomas Dimuzio: Sure, you can hear the overt tones of modules and instruments in recordings. It’s like hearing the difference between a Les Paul and a Stratocaster, but it rarely impacts my listening. As a mastering engineer I do tend to hear the intricacies of music, but I don’t usually listen with my mastering hat on; but it is easy to revert to a more technical and analytical side at times, especially when hearing a compelling piece for the first time. It’s the musician and engineer battling inside me.Tom Djll: I can sometimes ID Serge or Buchla-made sounds, but that’s about it. I would recognize Synchrodyne sounds, they are so unique. But working in music for so long has created a challenge in that it’s difficult, almost impossible, to turn off the “technical assessment” brain circuits and just enjoy the music.

What have you been working on lately, and do you have any upcoming releases or performances?

Thomas Dimuzio: I’ve just released my first proper Buchla LP called Sutro Transmissions on Resipiscent Records. It’s a live record recorded in San Francisco on the Haight and in the shadow of Sutro Tower. Another release entitled LCM is coming out this year on Erototox Records, which will be my second proper Buchla release. There are other duo projects in the works with Marcia Basset, Kris Force, Dimmer (with Joseph Hammer); a variation on Morton Feldman’s Triadic Memories with Tania Chen and Jon Leidecker, plus a bunch of other projects if I can ever manage to balance my time.Tom Djll: I have six or seven projects going at any one time, different groupings with like-minded players. With Gino Robair’s Unpopular Electronics, in 2019 I collaborated with the Rova Saxophone Quartet, and hope to do more. Gino and I are 2/3 of Tender Buttons, with pianist Tania Caroline Chen, which has one LP released (Forbidden Symmetries, on Rastascan) and another nearing completion. We’ll be doing some shows on the West Coast in February 2020. Tim Perkis (of The Hub) and I have a long-standing duo, Kinda Green. There’s some stuff under that name on Bandcamp and we’re working on a very intriguing, fucked-up “fusion” direction at the moment, using heavily processed trumpet and his self-coded musical systems. Clarke Robinson (of Clarke Panels) and I occasionally perform as an electronic duo under the name Runcible Spoon Fight.

There’s also the work I do with Euphotic with natural sound artist Cheryl Leonard and Bryan Day, who is a master instrument maker/coder/provocateur. We each come at the music from wildly divergent backgrounds and approaches, yet, together we are able to create some uncanny soundscapes together. This last summer I released a solo work of circuit bent and modular electronics, Failed Ecosystems (also on Bandcamp) and in 2018 Other Minds released a collection of my early electronic work (Modern Hits netlabel). And there are several other recording projects under way that have less to do with electronics. I’ve been talking with saxophone barnstormer Jack Wright, an old friend, about a tour this spring, possibly West Coast.Gino Robair: Unpopular Electronics (with guest Tom Djll) has a CD in the works. We are also collaborating with the ROVA Saxophone Quartet on a new release.

Can you outline how you patched and performed your Modulisme session?

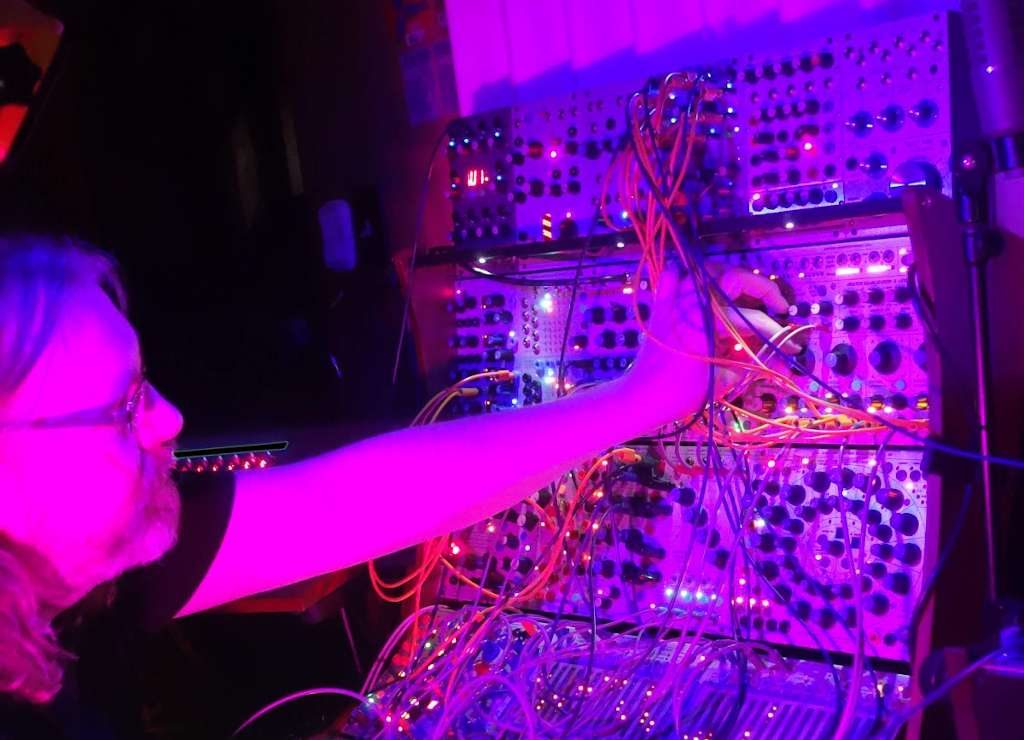

Thomas Dimuzio: I took ample time to pre-patch a 30U 200e, a 10U SkyLab and a 15U 200 clone. A couple days were spent building the patches with the goal to get all three systems patched up, interconnected and ready to interact live. Each of the five sections of the hour-long piece were recorded in realtime using variations of the patches. The piece was performed quadraphonically, but later mixed to a stereo along with editing to adjoin the five sections.

Tom Djll: I decided to go brutalist, and do a really “dry” concrete piece with a rigorously minimal set of resources. I used a portable lunchbox system running on USB charger power, as proposed by Tom Whitwell, and built for me by Clarke Robinson. I selected and populated the modules, which are, from left to right: Iaeskul F. Mobenthey Mister Grassi touch controller/rungler; Qu-Bit ION multiple function generator; Tiptop ONE sample player; 2HP FREEZ looper/granulator/decimator; Epoch Modular TwinPeak Filter; and an Erica Pico series Output. Even this small set of modules provides a lot of options. I’ve been working with this system for about two years, although not at all in the last year or so.So I came to it pretty fresh for the Modulisme piece.

I patched the system trying to maximize all outputs and control options. The Mister Grassi provides six outputs of high-speed “rungler” circuits, which, depending on the style of contact, deliver chaotic changing voltages, or, upon release, a steady randomly-determined voltage. Steady tones are also possible. (You can hear them occasionally throughout the piece.) Most of the rest of the system is driven by these voltages. EON is triggered from the Mister Grassi and it outputs gates, envelopes and waves to the filter and the sampler. Sometimes the FREEZ engages in a chattering loop captured from the ONE. Both of those modules can be triggered manually as well. The filter offers two inputs: one, right from the sampler, and the other from the FREEZ, which can be manually mixed. To select samples I used the dial on the ONE, with random results.

For sample sources I mainly used my own field and found recordings: birds; dragging, rubbing and striking objects around the home; odd trumpet sounds; feedback; noise toys; an old out-of-tune piano. I recorded seven or eight takes and used five, laid end-to-end, with no overlaps or overdubs or effects at all. The result is what you might call chance-determined concrete music.Who would your dream collaborator be for a Modulisme session or otherwise?

Thomas Dimuzio: John Paul Jones. We’ve corresponded here and there and I’d love to pursue a collaboration together. His Minibus Pimps is a fantastic project, plus he’s an expert at the Kyma to boot!

Tom Djll: These two guys: Gino and Thomas, of course!

Gino Robair: It would be fun to work with Björk, since my patches tend to have a polyrhythmic basis and I like her sense of rhythm.

- Thomas Dimuzio’s website, Bandcamp site.

- Tom Djll’s website, Bandcamp site, Soundcloud, YouTube.

- Gino Robair’s website.

- Modulisme.