To: Monsieur F., France

To: Monsieur F., France

London, Nov. 22nd __18.

It is just after midnight, and as I write these words, weak and weary, my hand scarce possesses enough strength to hold the pen. I am in a wretched condition. I cannot rest. No sleep will come to me. Its peaceful, blessed sanctuary seems now to elude me completely and, though the laudanum helps a little, the visions will not cease. As I toss and turn in my bed, wracked by torment, they besiege me. I see virginal brides as they file past tombs, all strewn with time’s dead flowers, bereft in deathly bloom. Truly, it is a hideous sight.

Instead I seek solace and contemplation in my study, writing these missives to you, with the comfort of a little whisky.

My only companion is the new wax cylinder which has recently arrived for the gramophone, and whose spirit of life animates my exhausted body. I will take it now from within the black box where it resides, reposing on the red velvet lining, and listen to it once more. It is a dark and brooding affair and, as the rain beats against my window pane, I will try to describe for you its uncanny yet irresistible call.

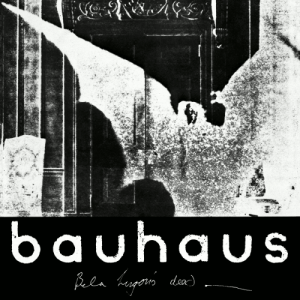

It was sent to me by Leaving Records (in partnership with Stones Throw Records, both esteemed associations based in the Americas), and captures the first five songs ever recorded by the fledgling quartet who then went by the eerie moniker of Bauhaus. These four gentlemen first assembled during the end of the last century in the fine county of Northamptonshire. As of course you know, the products of that county’s long and esteemed tradition of shoe-making are surely the default choice of any respectable gentleman seeking a sturdy pair of Brogues or Oxfords. Why, only last month I myself purchased a beautiful pair of boots by local firm Loake & Sons, ones which combine their time-honoured expertise with the highest quality materials and… But my old friend, listen to me! I digress most grievously. I can only apologise and blame the fatigue and the ghastly visions, both of which have, I confess, upset the equanimity of my mind in no small amount.

Where was I? Ah yes, the music. Apparently, then known by the more unwieldy name of Bauhaus 1919, the band gave their first ever performance on New Year’s Eve of Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Eight at the Cromwell public house in the charming market town of Wellingborough. With an admirable momentum (undoubtedly the product of those febrile times, when the First Earl of Lydon had recently caused such a public stir with his antics), the young fellows of Bauhaus soon afterwards pooled their few silver guineas and took their lively energy to Wellingborough’s Beck Studios the following January. There, they committed five of their recent compositions to posterity.

Despite their callow youth, and the fact that only a mere five or so weeks had passed since their formation, the results were extraordinary…

(Midnight, the witching hour, has just struck. As the bells tolled out across the cold night air, I paused briefly from this epistle in order to draw back the curtain and observe for a moment the church. And what a strange and discomfiting sight I observed. Dozens, indeed perhaps hundreds, of bats were leaving the bell-tower. What could it mean? I shudder now at the very thought of it.

…despite the limited and largely-homemade facilities possessed by Beck Studios. Comprising a 16-track recording device, it afforded meagre luxuries, with guitarist Daniel Ash later recalling that “it was like walking into somebody’s living room. It had the tacky 70’s wallpaper and carpet on the floor”. The proprietor, a Mr Derek Tompkins, was a very enthusiastic smoker, and with the band also consuming a considerable quantity of tobacco, the studio was apparently wreathed in a thick fug of smoke for most of the recording session. When it became too much, Mr Tompkins would “just open the back door and get some of this lemon spray and spray the room, and we’d all start again”. A misting of Citrus lemon obviously has qualities most encouraging to industrious labour!

As was the fashion at the time, and no doubt given an extra fillip by the sobering fact that the band were paying for the studio time with their own money, all five compositions were recorded and mixed in matter of some four short hours. Time and tide wait for no man!

The songs themselves are fascinating and, I think, Janus-faced in their nature. “Some Faces”, “Bite My Hip” and “Harry” both look back to the punk and power pop styles which had dominated the music hall stage during the preceding years (they bear the imprint of both most strongly), and yet at the same time they obviously lay the foundation for the distinguishing style which was so soon to follow. Indeed, “Bite My Hip” is essentially the band’s Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Two single “Lagartija Nick” in a prototype, yet no less thrilling, form.

One of the remarkable facets of these recordings is that the distinctive Bauhaus sound is already so almost-fully formed ex nihilio. Mr Murphy’s rich, baritone voice is unmistakable, and already swooping and soaring most elegantly as the music throbs darkly beneath him. Mr Ash’s biting guitar sound is already highly prominent, and the rhythm section of sibling Messers J and Haskins lock together like the mechanism of the finest gentleman’s watch from Zürich.

Influenced as they were by The Clash, a flavour of the music of the Caribbean Islands, too, is detectable in the band’s sound, particularly on “Harry”, one of the band’s earliest compositions, of which Daniel Ash remembered “I had this 15-watt amp and I had this echo unit and [Pete] starting singing out of The Sun newspaper, and I’d be playing this reggae riff which ended up being a song called ‘Harry’.” Apparently, the song was an ode to a Miss Debbie Harry who, I’m led to understand, was a young American lady much admired. A wealthy heiress of the kind Mr Henry James writes so much about perhaps? Remarkable.

There can be no mistake in regard to the centrepiece of the affair, though. Falling only a little short of ten minutes’ duration, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” seems, at the recollection of Mr Ash, to have emerged as an almost complete and sui generis masterpiece:

The story with Bela was, I called Dave up, or he called me and said, “Dave I’ve got this riff, it’s a really haunting riff, and I’m not using normal chords. And it sounds really haunting”. And he said: “That’s really weird, you say that, I’ve got this lyric about Bela Lugosi – the actor who plays the vampire” and I said: “Really?” So, the next rehearsal, Dave gives the lyric sheet to Pete and Kevin starts playing that boss nova beat right off the back, and I start playing the riff, Dave comes in with the bass line – and Pete sings that melody pretty much as you hear it on the record, right off the back- boom! – it was written immediately, strange things… It was just magic right from the get go – we didn’t have to work it out – it was very strange that it was written within about half an hour.

Even after four decades – and no little imitation by those less inventive – the end results of this collective afflatus are extraordinary in their unsettling intensity: the insistent percussion gnawing subtly away at one’s consciousness; the bassline calm yet profoundly unsettling; Mr Murphy’s spindly and sepulchral voice as chilled as cold marble itself; the guitar wandering unconstrained through many different yet complementary modes and bearing, I’ve always maintained, the subtle imprint of Mr Roger Barrett, late of the parish of Cambridge. The WEM Copycat, such a delightful tool in the hands of Mr Barrett, is here used equally skilfully, but to a much more eerie effect by Mr Ash, mimicking as it does the sound of hundreds of pairs of tiny, membranous wings beating frantically against the night sky. The very sound of it leaves me somewhat disturbed. Indeed, I think I must pause for more laudanum.

When Bauhaus not long afterwards made their first public appearance here in the foggy metropolis of London, opening for Gloria Mundi at The Marquee Club (named, no doubt, in honour of your erstwhile countryman, the now-fashionable libertine de Sade), a number of commentators remarked on the profound influence that Gloria Mundi had on Bauhaus’ sound, shepherding it away from the legacy sounds of the previous period and more towards the dark power for which they justly then became famous. Gloria Mundi remain one of the great lost bands of the era – the British Museum considers their I-Individual album perhaps the foundational text of Goth, or its Rosetta Stone at the very least – but the evidence of “Bela” shows that it was not a case of complete transformation in Bauhaus’ case, more a confirmation around, and encouragement towards, a direction in which they were already clearly heading.

Armed only with an acetate (as I believe such new-fangled technologies are called) of these recordings and a large measure of youthful pluck, Mr Ash then duly took himself off by rail to London, where he attempted to interest some reputable music companies in Bauhaus’s wares:

I just booked in interviews with four or five big major record companies and went on my own to EMI, RCA, Decca and somebody else. I went in with the acetate under my arm…. and actually got interviews with these big A&R men. They all said the same thing — “This is great but it’s the sort of thing I listen to when I’m at home but it’s not going to sell”. I knew they were going to say that, though – but I was always in a fantasy world, thinking, they might just get what we’re doing here.

Despite Mr Ash’s admirable self-possession and, as they say in the vernacular of the East End, “brass neck”, these larger companies remained unconvinced. However, a trail of good fortune lead Bauhaus to sign eventually with the emergent independent label Small Wonder, owned and managed by Pete and Mari Stennett from their recording emporium of the same name in Walthamstow. Finalising the deal whilst consuming “Turkish cigarettes” (which I believe, my old friend, actually means hashish in cigarette form), Mr Stennett informed the band that there was “no money for promotion, but I’ll give you a 50/50 deal and let’s take it from there”.

Though Mr Ash may not have understood it at the time, such a laissez-faire approach was most likely a considerable blessing. Given that, like the renowned lady of the stage Miss Diana Barrymore, many bands have failed to prosper due to receiving “too much, too soon” in the questionable “care” of the larger companies, it is perhaps in retrospect most fortunate that Bauhaus’s still unfolding talent had time to grow and develop more gradually within the independent sector. Within a year the band would be signed by the influential label 4AD, and eventually again by their parent concern, Beggars Banquet.

Released in August of Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Nine, Small Wonder’s “Bela” single swiftly accrued many admirers, one of which was, unsurprisingly, Mr John Peel, the noted personality of the radiogram. Playing it many times, Mr Peel soon made his appreciation more tangible by invited the band to perform in one of his celebrated Peel Sessions. Recorded in early December, the session comprised three original compositions (together with a commendable cover version of “Telegram Sam”, Mr Marc Bolan’s thrilling ode to the latest form of high-speed communication) which would later emerge on their début long player waxing In The Flat Field at the end of Nineteen Hundred and Eighty. And from there, the band’s trajectory described an impressively-upward arc of ambition and achievement. I believe that your acquaintances Messers Parsons and Olivetti have recently provided much insight into some of this later work.

I fear now, though, that my pen grows fatigued. Alone in a darkened room, my swelling heart involuntarily pours itself out thus. But I must finish, for this effort has taken much from me. Heaven bless my beloved editor.

D.S.

Post Script – Do you think that it could be this music that is causing my terrible visions, and exerting such a dread influencing upon my dreams? Perhaps I should resolve to travel to Vienna in order to consult with Dr Freud.

[show_more more=”Show the less gothic version” less=”Show only the gothic version”]

To: Monsieur F., France

London, Nov. 22nd __18

It is just after midnight, and as I write these words, weak and weary, my hand scarce possesses enough strength to hold the pen. I am in a wretched condition. I cannot rest. No sleep will come to me. Its peaceful, blessed sanctuary seems now to elude me completely and, though the laudanum helps a little, the visions will not cease. As I toss and turn in my bed, wracked by torment, they besiege me. I see virginal brides as they file past tombs, all strewn with time’s dead flowers, bereft in deathly bloom. Truly, it is a hideous sight.

Instead I seek solace and contemplation in my study, writing these missives to you, with the comfort of a little whisky.

My only companion is the new wax cylinder which has recently arrived for the gramophone, and whose spirit of life animates my exhausted body. I will take it now from within the black box where it resides, reposing on the red velvet lining, and listen to it once more. It is a dark and brooding affair and, as the rain beats against my window pane, I will try to describe for you its uncanny yet irresistible call.It was sent to me by Leaving Records (in partnership with Stones Throw Records, both esteemed associations based in the Americas), and captures the first five songs ever recorded by the fledgling quartet who then went by the eerie moniker of Bauhaus. These four gentlemen first assembled during the end of the last century in the fine county of Northamptonshire. As of course you know, the products of that county’s long and esteemed tradition of shoe-making are surely the default choice of any respectable gentleman seeking a sturdy pair of Brogues or Oxfords. Why, only last month I myself purchased a beautiful pair of boots by local firm Loake & Sons, ones which combine their time-honoured expertise with the highest quality materials and… But my old friend, listen to me! I digress most grievously. I can only apologise and blame the fatigue and the ghastly visions, both of which have, I confess, upset the equanimity of my mind in no small amount.

Where was I? Ah yes, the music. Apparently, then known by the more unwieldy name of Bauhaus 1919, the band gave their first ever performance on New Year’s Eve of Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Eight at the Cromwell public house in the charming market town of Wellingborough. With an admirable momentum (undoubtedly the product of those febrile times, when the First Earl of Lydon had recently caused such a public stir with his antics), the young fellows of Bauhaus soon afterwards pooled their few silver guineas and took their lively energy to Wellingborough’s Beck Studios the following January. There, they committed five of their recent compositions to posterity.Despite their callow youth, and the fact that only a mere five or so weeks had passed since their formation, the results were extraordinary…

(Midnight, the witching hour, has just struck. As the bells tolled out across the cold night air, I paused briefly from this epistle in order to draw back the curtain and observe for a moment the church. And what a strange and discomfiting sight I observed. Dozens, indeed perhaps hundreds, of bats were leaving the bell-tower. What could it mean? I shudder now at the very thought of it.)

…despite the limited and largely-homemade facilities possessed by Beck Studios. Comprising a 16-track recording device, it afforded meagre luxuries, with guitarist Daniel Ash later recalling that “it was like walking into somebody’s living room. It had the tacky 70’s wallpaper and carpet on the floor”. The proprietor, a Mr Derek Tompkins, was a very enthusiastic smoker, and with the band also consuming a considerable quantity of tobacco, the studio was apparently wreathed in a thick fug of smoke for most of the recording session. When it became too much, Mr Tompkins would “just open the back door and get some of this lemon spray and spray the room, and we’d all start again”. A misting of Citrus lemon obviously has qualities most encouraging to industrious labour!As was the fashion at the time, and no doubt given an extra fillip by the sobering fact that the band were paying for the studio time with their own money, all five compositions were recorded and mixed in matter of some four short hours. Time and tide wait for no man!

The songs themselves are fascinating and, I think, Janus-faced in their nature. “Some Faces”, “Bite My Hip” and “Harry” both look back to the punk and power pop styles which had dominated the music hall stage during the preceding years (they bear the imprint of both most strongly), and yet at the same time they obviously lay the foundation for the distinguishing style which was so soon to follow. Indeed, “Bite My Hip” is essentially the band’s Nineteen Hundred and Eighty-Two single “Lagartija Nick” in a prototype, yet no less thrilling, form.One of the remarkable facets of these recordings is that the distinctive Bauhaus sound is already so almost-fully formed ex nihilio. Mr Murphy’s rich, baritone voice is unmistakable, and already swooping and soaring most elegantly as the music throbs darkly beneath him. Mr Ash’s biting guitar sound is already highly prominent, and the rhythm section of sibling Messers J and Haskins lock together like the mechanism of the finest gentleman’s watch from Zürich.

Influenced as they were by The Clash, a flavour of the music of the Caribbean Islands, too, is detectable in the band’s sound, particularly on “Harry”, one of the band’s earliest compositions, of which Daniel Ash remembered “I had this 15-watt amp and I had this echo unit and [Pete] starting singing out of The Sun newspaper, and I’d be playing this reggae riff which ended up being a song called ‘Harry’.” Apparently, the song was an ode to a Miss Debbie Harry who, I’m led to understand, was a young American lady much admired. A wealthy heiress of the kind Mr Henry James writes so much about perhaps? Remarkable.There can be no mistake in regard to the centrepiece of the affair, though. Falling only a little short of ten minutes’ duration, “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” seems, at the recollection of Mr Ash, to have emerged as an almost complete and sui generis masterpiece:

The story with Bela was, I called Dave up, or he called me and said, “Dave I’ve got this riff, it’s a really haunting riff, and I’m not using normal chords. And it sounds really haunting”. And he said: “That’s really weird, you say that, I’ve got this lyric about Bela Lugosi – the actor who plays the vampire” and I said: “Really?” So, the next rehearsal, Dave gives the lyric sheet to Pete and Kevin starts playing that boss nova beat right off the back, and I start playing the riff, Dave comes in with the bass line – and Pete sings that melody pretty much as you hear it on the record, right off the back- boom! – it was written immediately, strange things… It was just magic right from the get go – we didn’t have to work it out – it was very strange that it was written within about half an hour.

Even after four decades – and no little imitation by those less inventive – the end results of this collective afflatus are extraordinary in their unsettling intensity: the insistent percussion gnawing subtly away at one’s consciousness; the bassline calm yet profoundly unsettling; Mr Murphy’s spindly and sepulchral voice as chilled as cold marble itself; the guitar wandering unconstrained through many different yet complementary modes and bearing, I’ve always maintained, the subtle imprint of Mr Roger Barrett, late of the parish of Cambridge. The WEM Copycat, such a delightful tool in the hands of Mr Barrett, is here used equally skilfully, but to a much more eerie effect by Mr Ash, mimicking as it does the sound of hundreds of pairs of tiny, membranous wings beating frantically against the night sky. The very sound of it leaves me somewhat disturbed. Indeed, I think I must pause for more laudanum. When Bauhaus not long afterwards made their first public appearance here in the foggy metropolis of London, opening for Gloria Mundi at The Marquee Club (named, no doubt, in honour of your erstwhile countryman, the now-fashionable libertine de Sade), a number of commentators remarked on the profound influence that Gloria Mundi had on Bauhaus’ sound, shepherding it away from the legacy sounds of the previous period and more towards the dark power for which they justly then became famous. Gloria Mundi remain one of the great lost bands of the era – the British Museum considers their I-Individual album perhaps the foundational text of Goth, or its Rosetta Stone at the very least – but the evidence of “Bela” shows that it was not a case of complete transformation in Bauhaus’ case, more a confirmation around, and encouragement towards, a direction in which they were already clearly heading.Armed only with an acetate (as I believe such new-fangled technologies are called) of these recordings and a large measure of youthful pluck, Mr Ash then duly took himself off by rail to London, where he attempted to interest some reputable music companies in Bauhaus’s wares:

I just booked in interviews with four or five big major record companies and went on my own to EMI, RCA, Decca and somebody else. I went in with the acetate under my arm…. and actually got interviews with these big A&R men. They all said the same thing — “This is great but it’s the sort of thing I listen to when I’m at home but it’s not going to sell”. I knew they were going to say that, though – but I was always in a fantasy world, thinking, they might just get what we’re doing here.

Despite Mr Ash’s admirable self-possession and, as they say in the vernacular of the East End, “brass neck”, these larger companies remained unconvinced. However, a trail of good fortune lead Bauhaus to sign eventually with the emergent independent label Small Wonder, owned and managed by Pete and Mari Stennett from their recording emporium of the same name in Walthamstow. Finalising the deal whilst consuming “Turkish cigarettes” (which I believe, my old friend, actually means hashish in cigarette form), Mr Stennett informed the band that there was “no money for promotion, but I’ll give you a 50/50 deal and let’s take it from there”.Though Mr Ash may not have understood it at the time, such a laissez-faire approach was most likely a considerable blessing. Given that, like the renowned lady of the stage Miss Diana Barrymore, many bands have failed to prosper due to receiving “too much, too soon” in the questionable “care” of the larger companies, it is perhaps in retrospect most fortunate that Bauhaus’s still unfolding talent had time to grow and develop more gradually within the independent sector. Within a year the band would be signed by the influential label 4AD, and eventually again by their parent concern, Beggars Banquet.

Released in August of Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-Nine, Small Wonder’s “Bela” single swiftly accrued many admirers, one of which was, unsurprisingly, Mr John Peel, the noted personality of the radiogram. Playing it many times, Mr Peel soon made his appreciation more tangible by invited the band to perform in one of his celebrated Peel Sessions. Recorded in early December, the session comprised three original compositions (together with a commendable cover version of “Telegram Sam”, Mr Marc Bolan’s thrilling ode to the latest form of high-speed communication) which would later emerge on their début long player waxing In The Flat Field at the end of Nineteen Hundred and Eighty. And from there, the band’s trajectory described an impressively-upward arc of ambition and achievement. I believe that your acquaintances Messers Parsons and Olivetti have recently provided much insight into some of this later work.I fear now, though, that my pen grows fatigued. Alone in a darkened room, my swelling heart involuntarily pours itself out thus. But I must finish, for this effort has taken much from me. Heaven bless my beloved editor.

D.S.

Post Script – Do you think that it could be this music that is causing my terrible visions, and exerting such a dread influencing upon my dreams? Perhaps I should resolve to travel to Vienna in order to consult with Dr Freud.[/show_more]